It’s hard to make forecasts, especially about the future, goes the old saying (attributed to Yogi Berra and Mark Twain, among others), and anyone in the foreign exchange market will understand the pitfalls of trying to predict exchange rates.

This has been particularly true of the rand over the years. Due to its relatively high liquidity levels, it’s often used by foreign traders as a proxy for other emerging market currencies. This makes the rand susceptible not just to South African-specific issues, but also broader sentiment towards emerging markets.

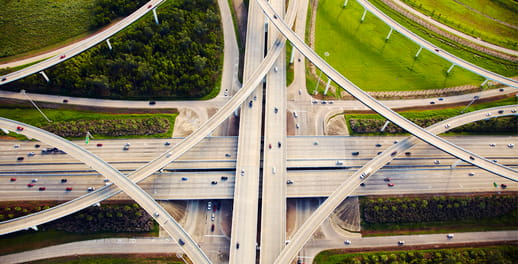

So anyone trying to forecast moves in the rand has not only had to deal with a plethora of domestic drivers – changes in the leadership of the ANC, sovereign credit ratings among them – but also global issues like US monetary policy and trade wars, which have more to do with what’s going on in Washington and Beijing than Pretoria.

As we’ve seen, sentiment around these drivers can change rapidly, rendering even the best econometric models futile at times. But understanding behavioural finance can help.

LISTEN TO PODCAST: Can behavioural finance make you a better investor?

Rand forecasters not only have to deal with a volatile local market, but also global issues like US monetary policy and trade wars, which have more to do with what’s going on in Washington and Beijing than Pretoria.

What is behavioural finance?

Behavioural finance has gained traction in recent years in academia and the financial services industry. Drawing on behavioural psychology, it can be applied to all areas of economic life, from personal finance to risk management.

At the heart of behavioural finance is the idea that we all suffer from certain cognitive biases that prevent us from making rational decisions. Some are the result of how we have evolved as humans, while others come about through the way we were brought up or through our experiences. The trauma of a market crash can make one overly conservative. On the other hand, a benign market over many years can make one overconfident. We tend to carry these biases not just into our personal decision-making, but also into our business decisions.

Although we can’t avoid these biases, we can recognise them when they arise, and have a strategy in place for working around them. In that way, we can make better (and hopefully profitable) decisions.

Let’s look at some of the better known biases and see how they apply to foreign exchange risk management:

Loss aversion

This describes our unwillingness to realise a loss, even when it is the rational thing to do. Think of an investor hanging onto a loss-making share, in the hope that it will recover, or a company persisting with an expensive software programme that it’s purchased, even after finding it to be inferior to a cheaper option.

Hindsight bias

This bias is the tendency to regard unlikely events as highly predictable in hindsight, like an upset in an election or sports match. It’s easy to figure out why a currency moved sharply after the event, but things are not so clear-cut ahead of the time.

Confirmation bias

This is where we seek out arguments or evidence that support our own view, rather than give due weight to opposing arguments. We all have our own philosophies and ideas about how the world works but this can make us ignore or underestimate key information.

Overconfidence bias

This is about overestimating our skill and decision-making ability and underestimating the role of luck when things go well. A good example of this is surveys that show the vast majority of drivers believe themselves to be of above average competence when statistically this is impossible.

Bandwagon effect

We don’t want to stand out from the crowd when we make a wrong decision, but we are happy to be wrong with the rest of the market, even though the economic result is the same.

The gambler’s fallacy

Just because the coin has shown tails for five throws in a row, doesn’t mean the sixth will be tails. Past events of this kind have no bearing on the immediate future. This is manifest in finance by attributing too much weight to recent market moves or performance.

We don’t want to stand out from the crowd when we make a wrong decision, but we are happy to be wrong with the rest of the market, even though the economic result is the same.

The availability heuristic

This is a fancy term for using readily available information (like a personal anecdote or experience) instead of proper analysis to make decisions. Statistics show clearly that smoking increases the risks of heart disease and cancer, but that doesn’t stop people mentioning their beloved great aunt who lived to 100 despite smoking two packs of cigarettes a day.

The behaviours described above will be familiar to any importer or exporter trying to manage their currency risk. Avoiding bias can be difficult though. For example, it’s easy to think we’re smart when a currency call goes right (overconfidence). Equally, it’s easy to jump on the bandwagon when the currency moves sharply – to overhedge after a sharp fall, or to neglect to take cover after a sharp rise.

Furthermore, during times of domestic political turmoil, it’s easy to overestimate the role of local affairs in setting the value of the rand, when it’s really global market sentiment towards emerging markets that is determining the rand/US dollar exchange rate (availability heuristic).

Four ways to manage our biases

Understanding behavioural biases is all well and good, but how can we recognise when we are falling into the trap and – by avoiding the traps – make better, more profitable decisions?

One thing we can do is to develop a strategy for recognising biases when they occur and setting out a game plan for managing them. We would recommend that a behavioural strategy should be part of the corporate treasurer or CFO’s toolkit. While the strategy should be designed around your business needs, they should entail the following:

- Have a specific strategy in place for your foreign exchange risk management. Develop a decision-making matrix out of this that also takes into account “fat tail” events (low likelihood but high impact events).

- Conduct regular critical and honest analyses of past hedging decisions, including (especially!) the ones that worked. This will help to discern luck from skill.

- Try to assign clear probabilities and timeframes to forecasts. There is no such thing as a perfect hedging decision, but you can learn to distinguish the 60/40 situations from the 40/60 ones. Clear timeframes will also help avoid loss aversion.

- Familiarise yourself with a list of cognitive biases and think of how these can affect your decision making.

Receive Focus insights straight to your inbox