What did you think of this webcast?

One of the raging debates in the investment community over the last few decades has been the battle between two styles, value vs growth. Like two great sporting rivals, each has its diehard supporters and each has enjoyed periods of dominance.

In recent times, growth has had the upper hand, and the extent of its outperformance has never been as extreme as it was towards the end of last year. The Covid-19 pandemic helped to supercharge the internet economy, and we effectively saw a decade of digitisation happening in a few months.

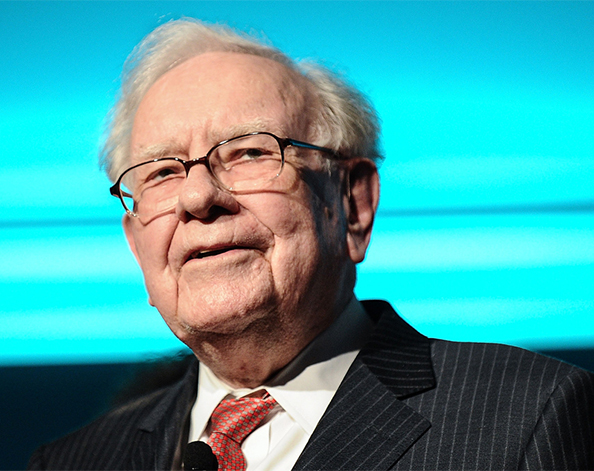

But is value vs growth a false dichotomy? That’s a question Max Richardson, senior investment director, Investec Wealth & Investment UK, put to Oaktree Capital’s Howard Marks, following the latter’s most recent memo, called “Something of Value”, which has generated a flurry of interest within the investment community.

Max questions whether the two styles are really mutually exclusive at all and whether the rivalry between them may be masking a more profound change taking place in the investment world. This is what Howard has to say.

Prefer to listen on the go?

The audio of the full conversation with Howard Marks is available as a podcast here, or wherever you stream your podcasts.

Subscribe to Investec Focus Radio SA

On how the two styles came into being:

Value investing traces its roots back to the 1950s, when Benjamin Graham crystallised the idea – though the term value investing only really came about much later.

“Warren Buffett calls Graham's style of investing ‘cigar butt’ investing,” Howard explains. “In other words he looked for cast-offs that one would find in the gutter, cigars that maybe had a puff or two left in them that he could pick up for nothing. And that was the style at the time.”

Howard adds that this all took place in what he calls a “dumb” environment: “There were no data, no computers, no spreadsheets, no screening programmes. If you wanted to get information on a company you would have write to the company and ask for their annual report and they would have to send it back once it went through their administrative process, all of which took time.

“Or you could look through dense publications that had data on companies, which most people did not bother to consult and so somebody like Graham or Buffett could find little-known situations where they could really scoop up incredible bargains because of other people's ignorance.”

Warren Buffett calls Graham's style of investing ‘cigar butt’ investing. In other words he looked for cast-offs that one would find in the gutter, cigars that maybe had a puff or two left in them that he could pick up for nothing. And that was the style at the time.

Growth investing emerged in the 1960s. “Growth investing was considered to be investing in great, fast-growing companies, which sell expensively but are worth it and that grew into something called the Nifty Fifty,” says Howard.

The Nifty Fifty refers to 50 fast growing companies listed on the New York Stock Exchange. “These were companies that were so wonderful that a) nothing bad could happen and b) there was no price too high,” says Howard. As a consequence, they sold very high price-to-earnings (PE) ratios.

“The normal PE ratio since World War Two has been 16 times earnings and many of the Nifty Fifty sold at a multiple of 30, 50, 70 and in some cases 90 times earnings,” says Howard.

“But of course it was worth it because they were such great companies,” he adds sardonically. However, the story ended in tears, as Howard explains: “If you had bought them the day I started work in 1969 and if you held them for five years, you lost almost all your money in the greatest companies in America because the stock market roughly halved and the Nifty Fifty did even worse.”

Lesson number one is that it's not what you buy, it's what you pay for it that determines whether you'll be successful or not. Lesson number two is that successful investing is not a matter of buying good things; it's a matter of buying things well.

On the lessons learned from over 50 years in the investment industry

Starting his career just as the Nifty Fifty era came to a shuddering halt had an enduring effect on Howard, since it meant that he could learn his toughest lessons early on, which he has used to great effect since.

“Lesson number one is that it's not what you buy, it's what you pay for it that determines whether you'll be successful or not. Lesson number two is that successful investing is not a matter of buying good things; it's a matter of buying things well,” he says.

However, there were many other lessons to be learned from the Nifty Fifty story, he explains. An example of one of the Nifty Fifty was Coca-Cola, a highly valued company that lost most of its value between mid-1972 and the end of '74.

“But another important lesson is that Warren Buffett, the high priest of so-called value investing, is perhaps best known for is his investment in Coca-Cola, which certainly was not a cigar butt,” Howard explains.

“He bought a great company at a fair price. Even if you had bought it at the high in 1972 and you held it for the next 26 years, you would have made a double-digit return for 26 years. If you can compound your money at a double-digit return for 26 years, you've made a lot of money. Buffett did it and that's one of the stories that is responsible for his success.”

Howard notes that Buffett has never been dogmatic about value and growth: “He says we don't practise something called growth investing or something called value investing. He didn't make that dichotomy and I think others shouldn't either.”

On generating returns in a highly competitive investment industry

Markets have moved on considerably since the days when a little extra homework could reveal hidden gems, bargains or the cigar butts referred to above. The investment industry draws some of the best brains from graduate schools, equipped with the data and tools they need to analyse companies.

“Today, careers in investing are highly sought after and we think of the industry as much more efficient,” says Howard. “Certainly one shouldn't think that, based on publicly available information, it's possible to get extreme bargains like Graham and Buffett did.

“Rather it's reasonable to think that if things are available at extremely low valuations there's probably a good reason, they probably deserve it and if things are expensive, there’s probably a good reason for that too, and they merit it. So, the thought that you can study public information and get rich from that is probably ill-conceived,” he adds.

“So, if the study of publicly available quantitative information is not going to be very profitable, then to be extremely successful as an investor you have to either deal with qualitative information about the present – the quality of a company's employees, engineers, thought process, product development capability, distribution capability – or guesses about the future or both.”

On why the question of sustainability is so important

Leading from this observation about the need for strong qualitative judgement is the issue on so many investors’ lips these days: sustainability. Max raises the importance of qualitative judgement and sustainability in the future in a world that is becoming more complex.

Howard agrees that one of the things that makes the future more uncertain are ESG / impact investing / sustainability issues. “Which companies can contribute to the well-being of the world 10 or 20 years from now? Which industries will come under a cloud? Which industries will be disrupted and extinguished because they are not relevant to the future? This is a very important decision and not made as easily as the question of what the current finances are,” he says.

Importantly, he says the companies that are best for society and the environment are not necessarily the ones that will generate the best returns. “It's not such an easy decision and the results are never clear cut,” he warns.

Trust us to manage your wealth today

On discerning growth and value in a rapidly changing world

Much of the complexity and difficulty in making qualitative judgements stem from the pace of change. Howard says that in today’s changing world, many companies that were successful 10 years ago are not successful today, while many of the companies that are successful today didn't exist 10 years ago.

Moreover, the nature of these businesses has changed. “The old companies were capital and asset intensive; they produced a physical product and they produced it in a physical setting of factories and equipment, which was expensive,” he says. But this has changed now, with companies less reliant on physical assets.

“We've never had companies as profitable as today's, with growth potential [that relies on] code and digitisation, engineers rather than equipment. If a software company develops a desirable app or piece of software and they produce a hundred of them, it costs several million. But the next hundred costs almost nothing and the hundred after that costs almost nothing so incremental profitability is extremely high and reliance on assets is extremely low,” he says.

“So, they have few assets and as a result they have this high ratio of price-to-assets but it's meaningless because their potential profitability is not asset-based, it’s idea-based, it’s code based.”

“So, the rules of the past that constrain the value industry, ratios like price-to-book, price-to-earnings and prices-to-sales – those ratios are the sine qua non of value investing but not as relevant in the new world.”

Howard stresses that he’s not simply saying one should invest in technology companies at the expense of the old mundane companies.

“You have to consider using all the tools in your toolbox – it's not that fast-growing companies are inexpensive companies are unimportant. Anything can be overvalued and thus likely to produce a poor return or undervalued and likely produce a good return.

“It's certainly possible for high growing, high growth tech and biotech companies to be so overpriced that they represent poor investments, remember, it's not what you buy, it's what you pay for it. There's no reason why a fast-growing company can't be good value or why a low multiple company can't be a good investment, but rather than say which is attractive today, my message is that investors should be broad-minded and open-minded,” he concludes.

Watch our previous webcast with Howard Marks

“History doesn't repeat itself, but it does rhyme.” It’s a well-worn adage, and one which invariably holds true when reading market cycles, says veteran distressed debt specialist Howard Marks.

About the author

Patrick Lawlor

Editor

Patrick writes and edits content for Investec Wealth & Investment, and Corporate and Institutional Banking, including editing the Daily View, Monthly View, and One Magazine - an online publication for Investec's Wealth clients. Patrick was a financial journalist for many years for publications such as Financial Mail, Finweek, and Business Report. He holds a BA and a PDM (Bus.Admin.) both from Wits University.

Please refer to the W&I Webinar Disclaimer and Data Protection Notice for the terms and conditions governing W&I webinars.

Receive Focus insights straight to your inbox