Receive Focus insights straight to your inbox

“It’s not about timing the market, but about time in the market,” goes the old saying. While it’s become a bit of a cliché, there’s an underlying truth to it. Those who stay invested over the long run in a well-diversified portfolio will generally do better than those who try to profit from turning points in the market.

There are a number of reasons why this is so, but they all boil down to two things: staying invested over the long-term has delivered the goods for investors over the years, as the performance of most of the world’s leading indices has shown. Conversely though, humans are notoriously bad at getting market timing right, made worse by the fact that the costs of getting it wrong are great. Let’s examine both of these.

The long-term case

Most long-term investors in equities accept that there will be periods when the market underperforms. However, they also know that equities have historically been the best means for growing wealth over the long-term.

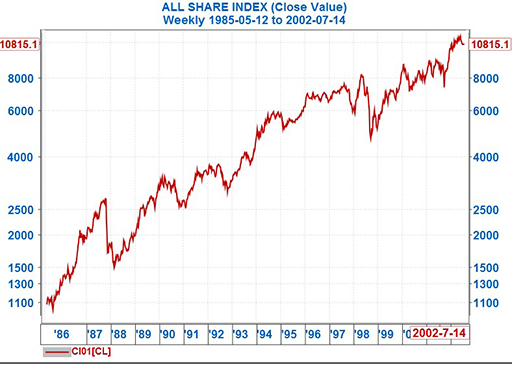

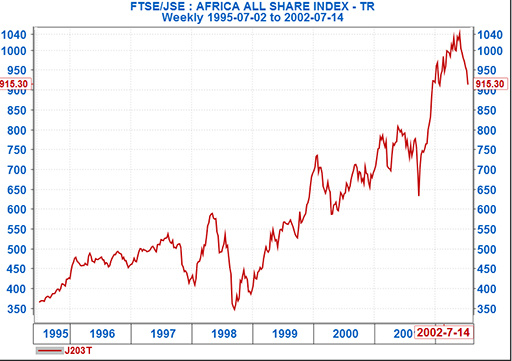

This is true even after taking market crashes into account. Any long-term chart of US equities shows events like the 1987 crash, the tech crash of 2000 and the 2008 financial crisis as small blips. It’s a similar story with the JSE, as our charts show. Equities have almost always delivered – time does heal old wounds when it comes to investing, sometimes spectacularly so.

Source: Iress

Source: Iress

According to a white paper by Investors Group, Why market timing doesn’t work, the S&P 500 has had negative annual returns 26% of the time since 1926, while the likelihood of the S&P 500 having a negative return over any 12-month period (not just a calendar year) is 27%, according to Bank of America Merrill Lynch.

While a one-in-four chance of a negative return doesn’t look appealing, losses are well covered by returns in the good years. The same research shows that the longer your time horizon, the better your chances.

Over five years, the chance of a negative return slips to 11%, over 10 years it falls to 6% and over 15 years to zero. That is to say, if you’d held US equities over any 15-year period since 1926, you would always have generated a positive return.

Why does staying invested over the long term work? One reason is the compounding effect of reinvesting the returns of your investment back into the market, such as dividends and interest.

This squares with research by Investec Wealth & Investment, which shows that even if you’d invested at the peak of the market ahead of the big sell-offs over the last three decades (before the 1987 crash, the 1998 Russian debt crisis, the tech crash of 2000/2001 and the financial crisis of 2008), you’d have substantially outperformed cash over the next 10 years (this assumed a portfolio of 60% equities in one of the JSE, S&P 500 and MSCI World and 40% bonds).

READ MORE: Why it doesn’t pay to time the market

Why does staying invested over the long-term work? One reason is the compounding effect of reinvesting the returns of your investment back into the market, such as dividends and interest.

Another is the discipline of the markets that rewards performance and punishes underperformance. Underperforming firms drop out of the major indices, while performers increase their share of the indices.

The perils of timing

But perhaps the best argument in favour lies in the risks and costs of the alternative approach: trying to time the market. Timing the market implies sitting out of the market for extended periods waiting for the right opportunity to enter. Investors using this approach often miss out on the incremental gains that are there to be had while they are waiting for the next big move to materialise.

As the numbers above show, your chances of experiencing a negative return on your portfolio diminish the longer you stay invested. Markets tend to throw up more surprises over the short term.

Trying to time the markets means exposure to other costs as well. Frequently buying and selling positions implies higher levels of brokerage and tax (direct and indirect), which also erode wealth over the longer term.

Your chances of experiencing a negative return on your portfolio diminish the longer you stay invested. Markets tend to throw up more surprises over the short term.

Those who try to time the market through geared instruments like futures also expose themselves to the risk of margin calls through short-term adverse moves.

And in timing the market we also leave ourselves more exposed to the behavioural biases that affect our decision-making. Put simply, long-term investing is an insurance policy against our own propensity to make mistakes.

READ MORE: Investing? Avoid these five cognitive biases

We know that time has a value and the longer that you have an investment that makes sense, the more you get paid for that and the more the internal compounding effect works for you.

As John Haynes, head of research at Investec Wealth & Investment UK, puts it: timing is impossible:

“[So] you don’t set up a process where you aim to do something impossible. You set up a process that accepts you’re going to be wrong most of the time and arbitrages the inefficiency that you can arbitrage, which is time itself. That is the only thing we can arbitrage effectively.”

“We know that time has a value and the longer that you have an investment that makes sense, the more you get paid for that and the more the internal compounding effect works for you,” concludes Haynes.

But remember to diversify!

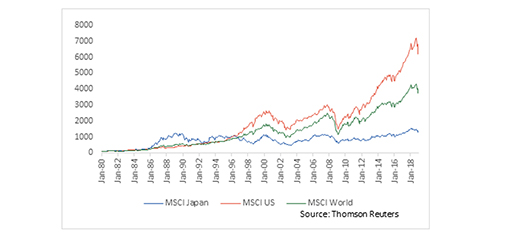

It should be noted that not all investments are created equal. While the compounding effect of investing over the long term can be impressive, that also depends on the quality of the investments. While the likes of the S&P 500 and the JSE (in rands) have performed for investors, that certainly isn’t the case for all equity markets.

A classic example can be found in the Japanese equity market. After rebuilding its economy in the post-war period, Japan experienced a boom in asset prices over the 1980s, particularly in equities and property. Much of this was fuelled by speculative buying.

The bubble burst in 1989 after the Nikkei had hit an all-time high of almost 40 000. It tumbled to below 20,000 within a few years but what has been more remarkable has been its poor performance since. It weakened even further thereafter, as Japan failed to tackle its structural problems and faced competition on the manufacturing export from other Asian countries.

Japan still lags the world and the US over a long-term horizon of 39 years. An investment of US$100 in Japan would now be worth US$1,280, in the US $6,210 and in the world, US$3,736.

The Nikkei was trading at 7,500 at the bottom of the financial crisis in 2009, since when it has recovered well, thanks to loose monetary and fiscal policy. At the time of writing in February, the Nikkei was trading around 21,000, an excellent performance over 10 years, but still well off the peak of 1989. Anyone who has been invested in Japanese equities over the last 30 years will understand the concept of the “lost decades”, as those years are referred to.

Our chart compares the MSCI Japan, MSCI US and MSCI World. Even with the boom years of the 1980s taken into account, Japan still lags the world and the US over a long-term horizon of 39 years. An investment of US$100 in Japan would now be worth US$1280, in the US $6210 and in the world, US$3736.

Ideally, you would have wanted to have been in US equities over the period, but the MSCI World Index, which represents the world’s leading equity markets, has served investors well over that time. The message is clear: invest for the long-term but stay diversified.

About the author

Patrick Lawlor

Editor

Patrick writes and edits content for Investec Wealth & Investment, and Corporate and Institutional Banking, including editing the Daily View, Monthly View, and One Magazine - an online publication for Investec's Wealth clients. Patrick was a financial journalist for many years for publications such as Financial Mail, Finweek, and Business Report. He holds a BA and a PDM (Bus.Admin.) both from Wits University.