As inflation continues to plague the world economy, central banks have maintained their aggressive frontloading strategies, and policy rate increases of a quarter of a percent are becoming increasingly rare. Indeed 50 basis points appears to have become the new 25. In many economies, dollar strength has been an additional source of price pressure and some central bank tightening appears to have been conducted with the currency in mind, a far cry from the competitive devaluations common before the pandemic. For now we suspect this direction will continue, but as global momentum slows, we expect inflation will begin to decline sharply, encouraging monetary authorities such as those in the US and UK to ease policy next year. We have nudged down our baseline case for world Gross Domestic Product (GDP) growth to 2.5% (from 2.6%) this year and for next year to 2.2% (from 2.3%). The principal risk comes from a cessation of European gas imports from Russia, which would be likely to drag the continent into recession. The recent rise in gas prices, if sustained, would add more to inflation and subtract more from growth than our current projections factor in.

In July, the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) unanimously voted to raise the federal funds rate by 75 basis points for the second meeting running, to 2.25-2.50% to combat soaring inflationary pressures. There are signs, however, that the US economy is starting to struggle under the aggressive policy action by the Fed. Indeed, housing market indicators are flashing red and businesses are becoming ever more pessimistic. Financial markets are also warning of an impending slowdown – the 2-year-10-year treasury curve is the most inverted since 2000. We recognise the risks and have lowered our growth forecasts to 1.9% this year (previously 2.5%) and 0.6% next (previously 1.0%).

The last month has seen the European Central Bank (ECB) join the ranks of central banks tightening policy, with a 50 basis point hike in all the key interest rates. Given continued inflationary pressures, we see policy being frontloaded with the deposit rate expected to rise to 1% by the end of this year. However, the outlook is fraught with risks. For one, the ECB needs to balance the need to tighten policy against preventing any unwarranted rise in fragmentation. But secondly and more critically is the risk around gas supplies. Our base case for growth has been downgraded to 2.7% (2022) and 1.3% (2023) on the assumption that the euro area avoids an energy crisis, but the risk of Russia halting gas supplies and the consequent rationing is very real.

Former Chancellor Rishi Sunak and Foreign Secretary Liz Truss are the two remaining candidates to replace outgoing Prime Minister Boris Johnson, who resigned on 7 July. Whoever wins will be tasked with tackling the UK’s cost-of-living crisis, which we expect will see Consumer Price Index (CPI) inflation rise to 12.3% in October, with upside risks given the gas outlook. To attempt to tame price growth, the Bank of England has raised rates by 50 basis points on 4 August, and we expect this to be followed by two more 25 basis point hikes this year. Following that, amidst a weaker economic backdrop, we see three 25 basis point cuts in mid-2023. But headwinds will hold sterling back in the near term, and we expect a weakening to $1.19 and 88p against the euro by end-year, followed by a modest rebound next year.

Global

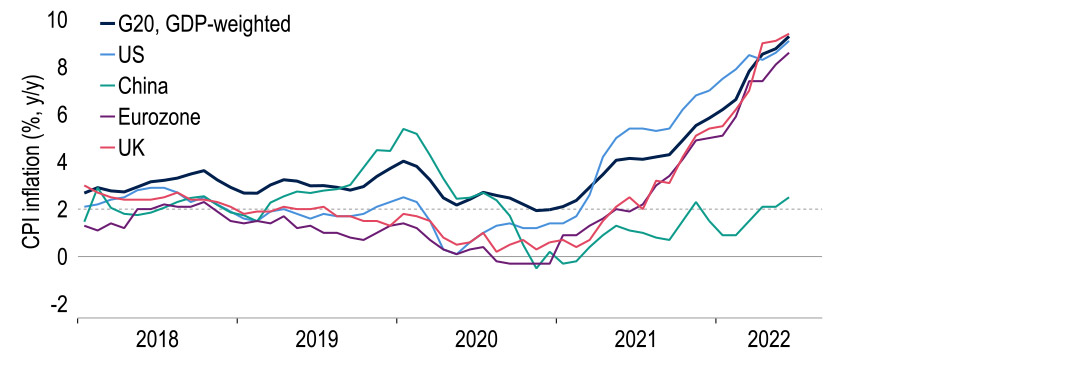

Inflation continues to plague the world economy. In the G20, 17 of the individual countries or areas have reported increases in annual inflation rates. Meanwhile, central banks have maintained their ‘frontloading’ strategies – the ECB (up by 50 basis points), Bank of Canada (by 100 basis points), Reserve Bank of India (by 50 basis points) and South African Reserve Bank (by 75 basis points) all pushed rates up in excess of consensus forecasts. The UK Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) has also raised its policy rate by 50 basis points on 4 August, marking the first hike in excess of 25 basis points since the Bank of England was granted operational independence 25 years ago.

Chart 1: Inflation continues to rise globally, despite aggressive central bank action

Sources: Macrobond and Investec

The dollar has continued to climb. Earlier in 2022, the main driver was a favourable shift in prospective short-rate differentials, notably with the euro. These spreads have reversed, but the US unit is now supported by negative market risk sentiment, as investors seek safe haven assets. Whatever the reason, in non-US economies the US dollar’s strength is raising price pressures, adding to arguments for higher rates. This marks a reversal from prior years, when central banks strove to gain competitiveness by easing policy and weakening their currencies. Terming the current situation a ‘competitive revaluation’ might be a bit of a stretch, but it does capture those inflationary side effects stemming from a firmer dollar.

That said, there are rays of hope that inflation may be close to a peak in some economies. Various idiosyncratic price rises e.g. used cars, appear to be cooling, perhaps as supply chain issues have dissipated. Also, various key commodity prices are off their highs, partly thanks to global downturn fears. For example, oil, copper, iron ore, aluminium, wheat and corn have all fallen back. As we have stressed previously, even a flat profile would result in downward pressure on annual inflation rates as previous sharp increases drop out of the calculation. The jury is out, however, on the likelihood of second round effects via labour markets. Moreover, a scenario of severe gas shortages poses upside risks to inflation as well as downside risks to growth.

Also firmly in that category is the Chinese outlook. June’s brief lockdown hiatus likely staved off a year-on-year contraction in second quarter GDP, but at 0.4% it was nothing to write home about. Indeed, some Chinese cities have imposed restrictions upon activity once again, bearing bad news globally for both the growth and inflation outlooks. Discounting the possibility of favourable back revisions, and/or a huge injection of policy stimulus, achieving the Chinese Communist Party’s 2022 growth target of 5.5% looks increasingly difficult. Following a weaker Q2, our forecast is reduced by 0.4 percentage points to 3.5%, and our 2023 number is pushed up to 5.2% by base effects.

The balance of evidence over the past month suggests a further cooling in global economic momentum. Among the more significant downward revisions to our GDP forecasts for this year and next are the US, the euro area, India and Japan. Overall, we have downgraded our 2022 world growth forecasts a touch to 2.5% (previously 2.6%) and those for next year to 2.2% (was 2.3%). This would not quite meet the World Bank’s definition of a global recession, ‘an annual contraction in world real per capita GDP (economic growth of <1%) accompanied by a broad decline in various other measures of global economic activity’.

Among the more significant downward revisions to our GDP forecasts for this year and next are the US, the euro area, India and Japan.

But our forecasts are well below the International Monetary Fund’s new interim projections of 3.2% and 2.9%, while next year’s is close to its downside scenario (2.0%), which includes European gas imports from Russia declining to zero. We view such a scenario resulting in world growth closer to 1% next year. Supply chain issues remain a risk. The CPB Netherlands Bureau for Economic Policy Analysis index suggests that global trade volumes began to rise again over the spring after a hesitant start to 2022, with Chinese activity recovering as the authorities eased lockdowns. But it is possible that China continues to struggle with its zero Covid policy and is forced to lock its economy down periodically, resulting in interruptions to global supply chains and an adverse mix of growth and inflation pressures.

United States

At the latest meeting, the FOMC opted once again to raise the Federal funds target range by 75 basis points to 2.25-2.50%. Although he was careful to leave all options on the table, Fed Chair Jerome Powell signalled in the post-announcement press conference that smaller increment hikes are likely. We envisage a 50 basis point hike in September followed by a final 25 basis point hike in November, leaving the target range at 3.00-3.25%. This path would result in a total of 300 basis points of rate increases over the course of this year, not including the impact of quantitative tightening. The last time we saw such an aggressive tightening over a twelve-month period was in the late 1980s.

It is clear that the current tightening cycle has been the most aggressive of this century as the Fed responds to the high inflationary environment. Since 2000 (excluding the current surge), CPI inflation has hovered around 2%, peaking at 5.6% in 2008. That is a far cry from what we are seeing today, with CPI inflation hitting 9.1% year-on-year in June, driven higher by energy prices. There are encouraging signs that we may be near the peak, however, supporting our call that the Fed will embark on a policy hiatus by year-end. ‘Core’ CPI inflation has now fallen for three successive months and inflation expectations have ticked down. Whether this can be sustained is dependent on the (lack of) wage response, a risk given the tightness of the labour market.

It is clear that the current tightening cycle has been the most aggressive of this century as the Fed responds to the high inflationary environment.

Indeed, the current tightness reflects the recovery in demand from the pandemic lows, whilst the participation rate remains at subdued levels. As such, unfilled vacancies are high, resulting in unmet economic potential. Warning sounds are ringing; businesses are growing more pessimistic about the future, which could alter investment and spending plans – the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia measure hit its worst level in over 40 years. Although we do not think the economy is in a broad-based downturn yet, as per the textbook definition, the US economy is technically already in a recession (negative growth in Q1 and Q2). This was largely due to inventory swings though, with consumption growth still positive in the first half of 2022.

Despite the technicalities, we believe that the pessimism about the future reported in surveys is warranted. Our base case looks for a more widespread slowdown in mid-2023. We think the US economic outlook will deteriorate under the weight of tighter monetary policy next year. Indeed, the housing market is likely to struggle under higher mortgage rates – despite some recent respite, the average 30-year contract rate is near 6%, double that of the pandemic trough. As such, we see a short, mild recession, consisting of negative quarters in Q2 and Q3 of 2023. As demand slows, this should help inflation pressures to ease, opening the door to three 25 basis point rate cuts in mid-2023 to support the economy.

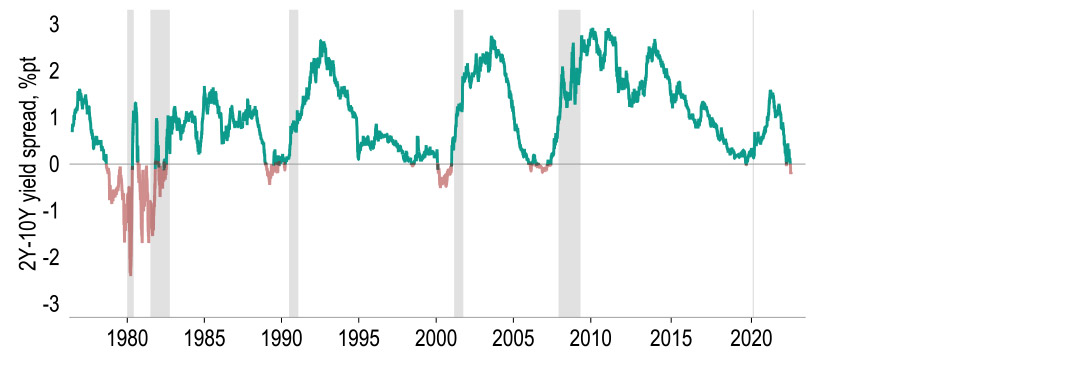

Markets are also signalling belief of an impending economic slowdown. The US Treasury yield curve (2-year-10-year) has inverted. Although lead times have varied, yield curve inversions have preceded every US recession since 1955 and, as such, is a closely watched signal of an impending downturn. However, in the past it has given false signals, such as in 1998 where the curve inverted but we did not see a recession, likely thanks to the Fed cutting rates three times to support the economy. Looking ahead, given our expectation of three 25 basis point rate cuts next year, we expect longer-term yields have further to fall – our end-2023 10-year US treasury forecast remains unchanged at 2.50%.

Chart 2: Inversion of the US yield curve warns of impending recession

Grey bands signal recession as defined by the NBER

Sources: Macrobond, Investec

The lowering of the yield curve would lend support to equities, just as a higher curve has weighed on the market earlier in the year. Indeed, lower longer-term yields will also reflect the deteriorating economic outlook, which is consistent with our new weaker growth forecasts, of 1.9% this year and 0.6% next (previously 2.5% and 1.0%). Lastly, a broader weakening of the global growth outlook lends favour to the US dollar. We still expect the strength to unwind gradually, albeit from a greater level.

Eurozone

July’s ECB meeting saw it join the ‘50 club’, delivering its first hike since 2011. The key rates all rose by 50 basis points, taking the deposit rate to 0.00%. This was a larger hike than previously guided, driven by the ECB’s assessment of a ‘materialisation of inflation risks’. That now puts the emphasis on frontloading hikes, an approach the ECB argued is supported by the establishment of its new anti-fragmentation tool, the Transmission Protection Instrument (TPI). We believe rates will rise by 50 basis points again in September, prompted by another upward revision to its inflation forecasts. We expect a further two 25 basis point hikes in October and December, lifting the deposit rate to 1% by year-end.

Inflation worries are clearly evident, with President Lagarde citing four factors behind the more aggressive action: i) June’s Harmonised Index of Consumer Prices (HICP) record of 8.6%, another clear overshoot of the ECB’s forecasts (by 0.5 percentage points for Q2); ii) strong momentum across nearly all categories in month-on-month seasonally adjusted inflation; iii) continued strength in core inflation – the dip to 3.7% in June reflects special one-off factors (Germany slashed regional transport costs) and upward pressure should resume in the near term. Indeed, we do not foresee any downtrend until early 2023 and still see it above the 2% target at the end of next year; iv) the euro’s weakness and its impact on prices.

Against this backdrop, the ECB faces the difficult task of tightening policy whilst preventing any ‘unjustified’ widening of sovereign yield spreads. Flexible pandemic emergency purchase programme (PEPP) reinvestment represents the first line of defence. But we see this as being insufficient given it relies on reinvesting maturing core (Germany, France, Netherlands, Belgium Austria) bonds into peripheral markets, which right now is not possible given negligible amounts of these bonds maturing in the near term. To better tackle this issue, July saw the launch of the TPI. This new instrument will allow the ECB to buy EU19 government bonds to counteract ‘unwarranted and disorderly’ market moves without restrictions ex ante. The ECB will be hoping the latter point is enough to reassure investors.

TPI’s introduction is timely given the fall of the Italian government and early elections (25 September). Consequently, the Budget may be delayed, putting further funds from NextGenEU at risk given they are conditional on targets being met: €22bn is due over the second half of 2022 and €20bn in 2023. This could also jeopardise TPI support given its conditionality against various fiscal criteria, but as use of the TPI is ultimately at the ECB’s discretion, it can take a pragmatic approach. Even so, a key question hangs over the shape of the new government, given polls show the ‘centre-right’ group, which includes the far-right Brothers of Italy, is on track for a majority. This prospect may unnerve markets, put further pressure on spreads and test the ECB’s resolve.

For the new Italian government as well as all those around the EU19, the biggest challenge is addressing the soaring cost of living. Coupled with ongoing supply chain issues and uncertainty around the Ukraine war, this has led us to downgrade our GDP forecasts. We believe a recession will be avoided, but risks are skewed squarely to the downside. Our estimates now stand at 2.7% for 2022 and 1.3% in 2023, with the slowdown leading to a pause in the tightening cycle, our end 2023 deposit rate forecast at 1.00%. This is predicated on the absence of a complete gas squeeze. There is a very real risk that Russia shuts off supplies, leading to rationing, which in a worst case scenario we estimate could cut EU19 GDP by 6%.

There is a very real risk that Russia shuts off supplies, leading to rationing, which in a worst case scenario we estimate could cut EU19 GDP by 6%.

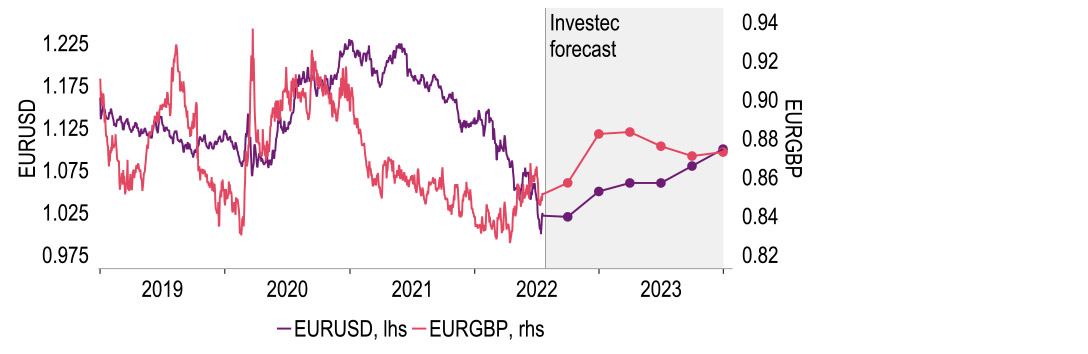

These energy risks have contributed to the euro’s recent pummelling. That combined with continued dollar strength saw the euro-dollar rate dip below parity (intraday) for the first time since late-2002. The ECB’s 50 basis point hike has offered minimal support, while the political risks stemming from Italy also pose a threat. On balance, we continue to hold the view that the euro will strengthen, albeit from, and to, a lower level than a month ago. This is largely given our assumption that gas remains flowing throughout the winter. In addition, given the later start of the ECB’s tightening cycle, its rates can remain on hold next year while other central banks ease. Our revised end-year targets for the euro are $1.05 and 88p against the pound (previously $1.10 and 88p).

Chart 3: Euro to strengthen but from, and to, a lower level

Sources: Macrobond and Investec

United Kingdom

Months of speculation over the longevity of Boris Johnson’s tenure as prime minister ended with his resignation on 7 July. In what was an atypical market immediate reaction in such circumstances, sterling rose on the news. This may have been on the hope that the next prime minister could take a more conciliatory stance in discussions around the Northern Ireland protocol, reducing the risk of mounting trade frictions with the EU, and/or on hopes pressures for Scotland’s IndyRef2 could ease. The decision on who will replace Johnson for the remaining duration of the parliament lies with the approximately 160,000 Conservative Party members now that members of parliament have whittled down the choice to ex-Chancellor Rishi Sunak and Foreign Secretary Liz Truss.

Neither has signalled any intention to withdraw planned legislation to unilaterally override the NI Protocol. The key dividing line between them is fiscal policy. Truss is advocating a loosening of the fiscal stance of at least £30bn, including the reversal of April’s National Insurance Contributions hike and scrapping the planned Corporation Tax rise. Sunak, meanwhile, is arguing that at present this is undesirable as it would risk adding to inflationary pressure. Also, June’s £19.4bn interest bill for inflation-linked debt, more than double the previous monthly record, reinforces the argument that the public finances leave little room for fiscal giveaways.

We see headwinds still holding the pound back in the near term. One of these is the likely recession.

Indeed, October’s new energy price cap will see another jump in price indices, which could spark a new record interest payment in December via uplift to index-linked gilts. Incorporating our utilities analysts’ latest energy price cap estimates, our new inflation forecasts see a peak of 12.3% in October. While led by energy and food, core price pressures will remain elevated. Using a Banque de France framework, we have estimated a ‘Fine Core’ measure of UK inflation, which excludes more volatile index components on a statistical basis and in theory gives a better gauge of underlying price pressures. This points to inflation slightly above the Office for National Statistics’ core measure (CPIY), which itself will likely remain above target through next year.

Taming inflation will require a number of ingredients. Some are outside the Bank of England’s control, e.g. commodity prices stabilising or retreating, supply chains unclogging. But what the MPC can influence is the degree to which activity cools, and with it the labour market. A string of relatively resilient indicators, along with revisions to back data, have prompted us to nudge our GDP forecasts up a little from last month, by 0.2 percentage points to 3.5% for this year and by 0.1 percentage point to 0.6% for 2023. This, at the margin, might make the MPC more hawkish and determined to front-load rate hikes, as many of its peers globally have done recently.

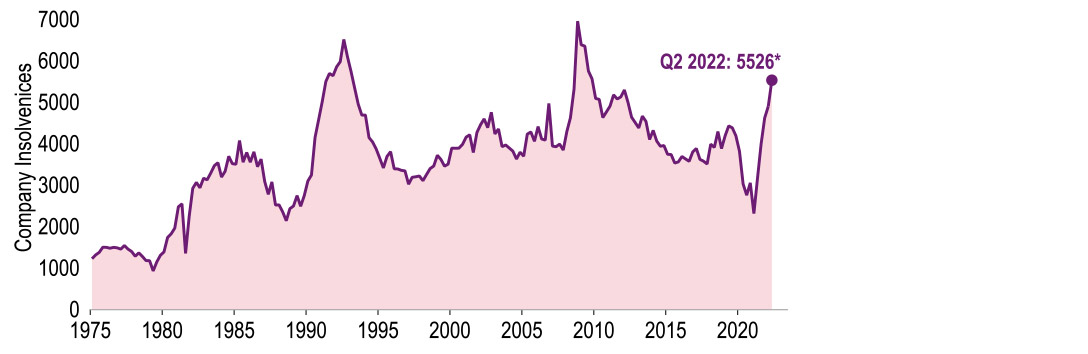

The Bank of England has just announced a 50 basis point rate rise, and we are pencilling in a year-end bank rate of 2.25%. But the decision is not a straightforward one. The rebound in labour market participation recently hints that some of the scarcity of labour could dissipate. And whereas GDP growth looks resilient on the surface, some signs of mounting stress in the corporate sector are appearing, judging by the climb in corporate insolvencies in Q2 to what looks like their highest since the global financial crisis. We continue to expect the UK economy to enter a recession around the turn of the year and the bank rate to be cut from mid-2023, to 1.50% by the end of the year.

Chart 4: Company insolvencies in England and Wales are at their highest since the GFC

*Estimated using NSA UK Insolvency Service data

Sources: UK Insolvency Service, Macrobond and Investec

As far as sterling is concerned, we see headwinds still holding the pound back in the near term. One of these is the likely recession. Another is that neither of Johnson’s potential successors seem minded to adopt a more conciliatory stance to the EU after all. We forecast the dollar-pound rate at 1.19 and euro-sterling at 88p, both weaker than now. And with the Supreme Court hearing arguments on 11 and 12 October on whether Nicola Sturgeon can legislate for IndyRef2 despite the UK government’s objections, we see further downside risks. But were the dollar to weaken in 2023, sterling may strengthen against it and also (a tad) versus the euro by end-2023 (to 1.26 dollar and 87p).

Get more FX market insights

Stay up to date with our FX insights hub, where our dedicated experts help provide the knowledge to navigate the currency markets.

Browse articles in

Please note: the content on this page is provided for information purposes only and should not be construed as an offer, or a solicitation of an offer, to buy or sell financial instruments. This content does not constitute a personal recommendation and is not investment advice.