Markets throw investors a (yield) curveball

Yields have risen globally since the start of the year as markets move to price in more aggressive monetary policy tightening. But the Russian invasion of Ukraine and the human tragedy unfolding there has brought the latest bout of uncertainty, clouding the outlook. Please read our monthly Global Economic Overview for our latest forecasts.

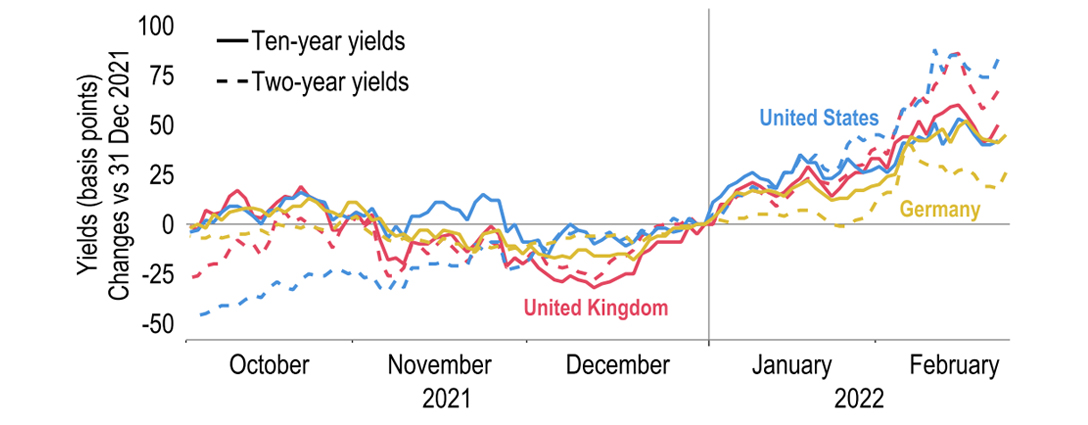

Yield curves have moved up sharply so far this year as inflation news has disappointed. We consider that too much tightening is being priced into curves such as the US, UK and the euro area over 2022, possibly as markets are fixated on very short-term inflation prospects. Indeed, inflation should abate through the course of the year. We note that in 1994, yield curves factored in very aggressive tightening through 1995, only for the Federal Reserve and the Bank of England (BoE) to cut rates after a relatively modest number of increases. While we do not currently envisage an explosion in pay growth, such an outturn could prompt aggressive policy responses by central banks. The war in Ukraine could also affect thinking on monetary policy.

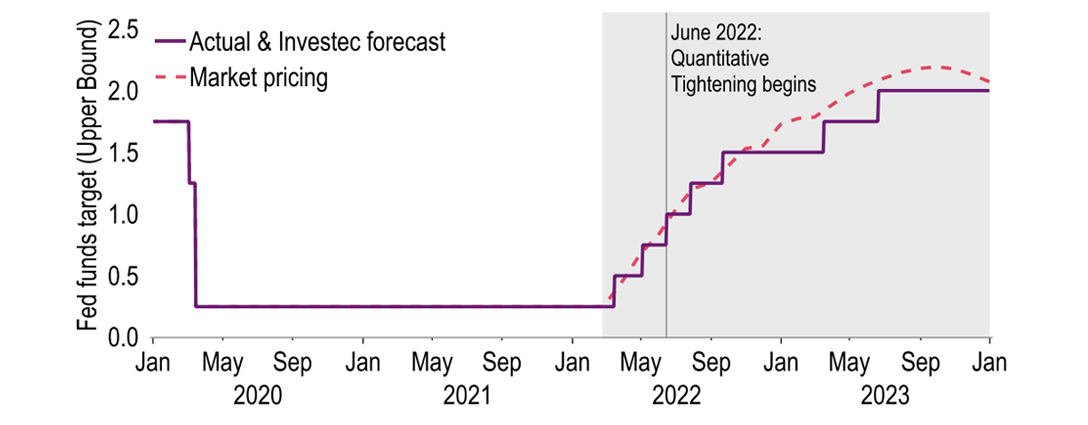

Reflecting on the intense inflationary pressures and tight labour market conditions, we still expect monetary tightening to commence with a 25 basis point increase in the Federal funds target range in March. Our view is that this will be followed by four further hikes this year, leaving the Federal funds target range at 1.25-1.50% by the end of the year. Accordingly, we have tweaked our 10-year Treasury forecast, and now have yields reaching 2.25% in the third quarter, rather than the fourth quarter of this year. This ties in with our assumption that quantitative tightening (QT) will begin in June, involving a runoff of maturing assets from the Fed’s balance sheet.

The euro area is also facing elevated levels of inflation and tightening labour markets, leading to the prospect of a faster pace of monetary policy normalisation than previously anticipated. Our own view now envisages an end to quantitative easing (QE) in September and the first rise in the deposit rate to 0.25% in December. In terms of our broader forecasts, we continue to expect a solid pace of growth this year and next at 4.1% and 3.1% respectively. Meanwhile, our market forecasts see 10-year bund yields reaching 0.75% and 1.00% at the end of the year, with the euro-dollar exchange rate attaining $1.18 and $1.22 in 2022 and 2023.

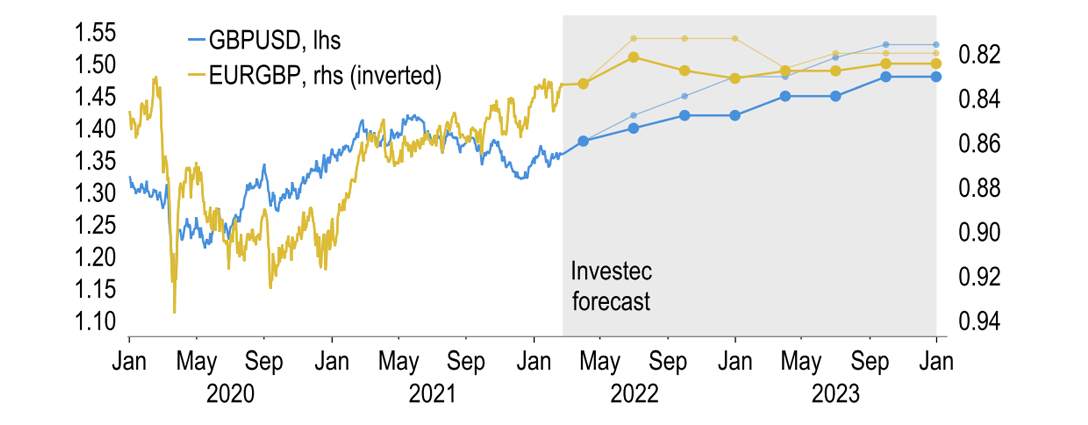

Activity looks likely to weather the inflation shock fairly well in the UK, and we expect robust gross domestic product (GDP) growth of 4.2% and 2.2% in 2022 and 2023. However, faced with surging Consumer Price Index (CPI) inflation and little labour market slack, we see the BoE front-loading more of its policy tightening. We now expect three further rate hikes of 25 basis points each this year, and then a pause to assess the effect of this and of balance sheet reductions, before a further two rate rises in 2023. Ten-year gilt yields would end 2022 at 1.50% and 2023 at 1.75%. Our forecast for sterling is for a rise in the pound-dollar exchange rate, or cable, to $1.42 and $1.48, respectively. This is somewhat less than we previously thought, as the adjustment to our rate forecasts in the US has been relatively larger.

Global

So far in 2022, yield curves have reacted strongly to upside inflation surprises. In the G10, 10-year sovereign yields have risen by up to 75 basis points. At the shorter end, expectations of policy tightening have become heightened. In the US, markets are pricing in six to seven 25 basis point Fed hikes this year, compared with three at the start of the year. This looks overdone as; i) easing supply bottlenecks in goods markets, such as cars, should push inflation down; ii) QT reduces the reliance on rate hikes; iii) higher inflation itself is likely to squeeze real spending power and therefore demand. Markets seem to be focusing excessively on the short-term outlook. In addition, central banks risk reacting too aggressively in attempts to safeguard their inflation credibility.

Consider the situation in 1994. Following the end of a long period of low US rates, global markets panicked and discounted aggressive tightening right through 1995. Was this justified? In short, no. UK and US rates peaked well below what had been priced in, and both the Fed and the BoE cut rates in 1995. A parallel scenario may emerge now where yield curves are overegging the number of hikes. If this influences central banks, they may tighten too much and need to reverse policy. Admittedly, it is not obvious how far and how quickly central banks should and will move. But this only serves to heighten the risk of market volatility and of central banks making a policy mistake.

Chart 1: Changes in key sovereign yields since the turn of the year (bps)

Sources: Investec, Macrobond

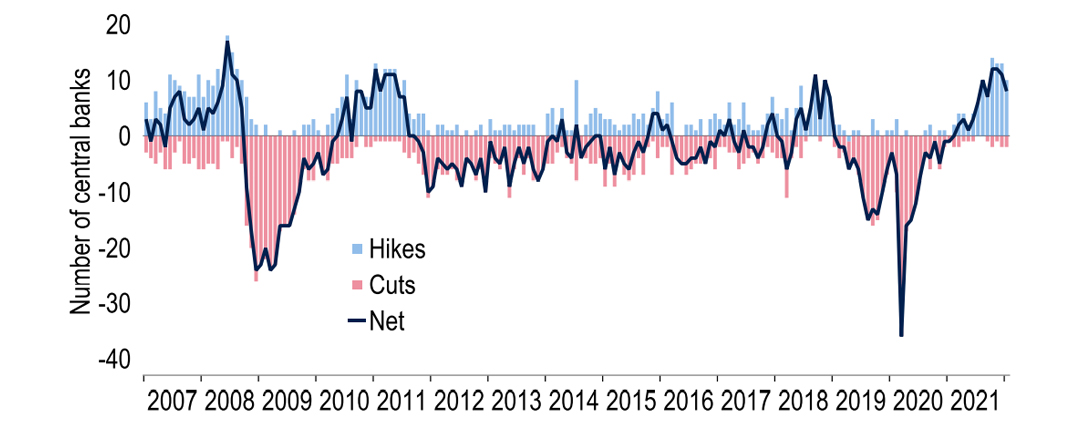

A major upswing in pay increases could justify central banks slamming on the brakes – but this should not be necessary. While wage growth seems to have gained ground in the post-pandemic world, it appears broadly contained. Note that we are not ruling out policy rates reaching 2% or more at some stage. However, we doubt this will occur over a 12-month timeframe and suspect it might take more than one cycle. Indeed, the 1995-1996 easing was relatively short-lived and the upward path of US and UK rates resumed soon after. Most but not all central banks have a tightening bias. The People's Bank of China as well as the central banks in Turkey and the DRC are all easing policy due to various idiosyncrasies.

President Vladimir Putin has escalated tensions further by ordering Russia's military command to put nuclear deterrent forces on high alert.

Whilst monetary policy is the key macro topic of 2022, the Russian invasion of Ukraine is an increasing concern. In response to the dramatic escalation in recent days, the West has ramped up sanctions on Russia. The UK, for example, has issued an asset freeze on all major Russian banks, prohibited Russian companies from raising finance on UK markets and stopped Russia issuing sovereign debt in London. Meanwhile, US President Joe Biden has cut off Sberbank from the US financial system, Russia's biggest bank that accounts for almost a third of Russia's banking sector. The US and its allies have also moved to prevent Russia's central bank from using its international reserves, and cut some of the country's key banks out of the international SWIFT financial payment system. The effect on Russia’s economy could be material. In response, President Vladimir Putin has escalated tensions further by ordering Russia's military command to put nuclear deterrent forces on high alert.

Chart 2: Most central banks now have a tightening bias – but not all

Sources: Macrobond, Investec

The market reaction to all this has seen the rouble collapse by 30% against the US dollar, prompting the Russian central bank to double its key interest rate from 9.5% to 20% in an attempt to cushion the depreciation. Unsurprisingly, the escalation in tensions has led to a wider risk-off movement in markets, pushing global bond yields lower and the US dollar higher, as well as fuelling a spike in oil and gas prices, with Brent crude back over $100 per barrel. Rising commodity prices has seen much talk of the possibility of major disruptions to energy markets, entailing a sharper cost of living crisis and pressure on growth.

Overall, the war’s market and economic implications will depend on what Putin's endgame is and the lengths he will go to achieve it, both of which are still unclear as it stands. Still, it’s probably safe to say even at this stage that the political ramifications are looking potentially seismic.

While geopolitical risks have risen to the fore, Covid-19 appears to be a dissipating risk. The Omicron wave seemed short, albeit elevated, based on evidence from South Africa and the UK. And indeed, global cases now look to have turned a corner. The first quarter will likely be weak for many economies, but countries are starting to move to a ‘living with the virus’ strategy, which should help activity normalise. Vaccinations and research will continue, with the emergence of new variants always a possibility – but our base case is that Covid-19 brings no more major disruption. With the absence of these risks, we are still looking for the global economy to normalise, with growth of 4.3% this year and 3.7% next.

United States

Some private forecasters now expect seven 25 basis point increases in the Fed funds target range this year, a scenario more akin to 2004 than 1994. There is also talk of a 50 basis point hike at some stage, as favoured by Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis President James Bullard. Is this possible? Yes, but perhaps unlikely. Consider these points: i) the Fed needs to maintain its inflation credibility; ii) QT will also tighten monetary conditions and may start relatively soon; iii) inflation should fall sharply through the second half of this year (the core personal consumption expenditures or PCE measure in December stood at 4.9%); iv) fiscal policy will provide waning support over 2022. Broadly, our base case is that the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) moves at its next meeting on 16 March and ‘front loads’ a series of hikes, but not aggressively.

December’s dot plot showed Fed members wanting between one and four 25 basis point hikes this year, with a median of three, and we will scour the new version closely on 16 March for updated clues to the committee’s thinking. Before this, Chair Jerome Powell will outline his thoughts at his semi-annual policy testimony on 2 March. The current FOMC includes three hawkish regional members (Bullard, Mester and George) but the three appointees for board positions (Bloom-Raskin, Cook and Jefferson) may give the Fed a more balanced tilt if and when they are appointed. Overall, we now see a total of five 25 basis point hikes in the Fed funds target this year – compared to our previous estimate of three – and two next year. We are of the view that QT will start in June.

The Fed is broadly satisfied with progress towards its maximum employment goal. U3 unemployment, which accounts for people who are actively seeking a job, is near historical lows at 4.0%, despite payroll numbers being two and a half million below the pre-pandemic peak – a consequence of a lower participation rate. The ‘great retirement’ is a significant contributor towards this, although the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ latest population re-estimations have reduced this effect. The new estimates have also resulted in a revision to the participation rate to 62.2%, from 61.9% in December. Overall, this should reduce fears over inactivity restricting the size of the labour market. Note too that participation is now two percentage points above the pandemic trough of 60.2%.

Chart 3: In house monetary policy forecast timeline – comparison with market pricing

Sources: Macrobond, Investec

A key consideration for policymakers is how these labour market conditions translate into pay growth, and more broadly, entrenched inflationary pressures. These concerns intensified in the third quarter of last year when the Employment Cost Index, a mix-adjusted measure of total pay, hit a 17-year high at 1.3% quarter-on-quarter. This increase was so stark that it prompted Fed Chair Powell to consider bringing forward the end of QE even sooner than planned. There was some relief in the third quarter, however, with growth cooling slightly to 1.0%, although this is still high by historical standards. We doubt labour market pressures are easing, but they may not be tightening as quickly as once feared.

CPI inflation hit 7.5% in January, with the cost of staples, such as food up 7.0% year-on-year, recording hefty price increases.

Inflation pressures, however, are intensifying, at least over the short term. Used car price growth remains a substantial contributor, with prices rising by 40.5% on the year in January, although Manheim car auction data suggests that price growth is finally topping out. Price pressures, however, are now much broader, with used cars not the sole story. Indeed, CPI inflation hit 7.5% in January, with the cost of staples, such as food up 7.0% year-on-year, recording hefty price increases. Such inflationary pressures are likely to squeeze household budgets, which could drag on growth. This is a key downside risk to our 2022 growth forecast of 3.7%.

Another point to note is rising housing costs. Higher Treasury yields have pushed the 30-year mortgage rate above 4% for the first time since 2019. While demand could initially pick up due to fears of costs rising further, ultimately, higher rates should cool the current hot market and translate into an easing of rental prices. As of late, rents have been pushed higher by a severe lack of supply – vacancy rates are currently at the lowest since 1984. Although rents, including ‘owners’ equivalent rent’, have been a key contributor to the surging CPI, they account for a far lower weight in the PCE (16% versus 32%), the Fed’s preferred inflation gauge – partially explaining the widening gap between the two measures.

Eurozone

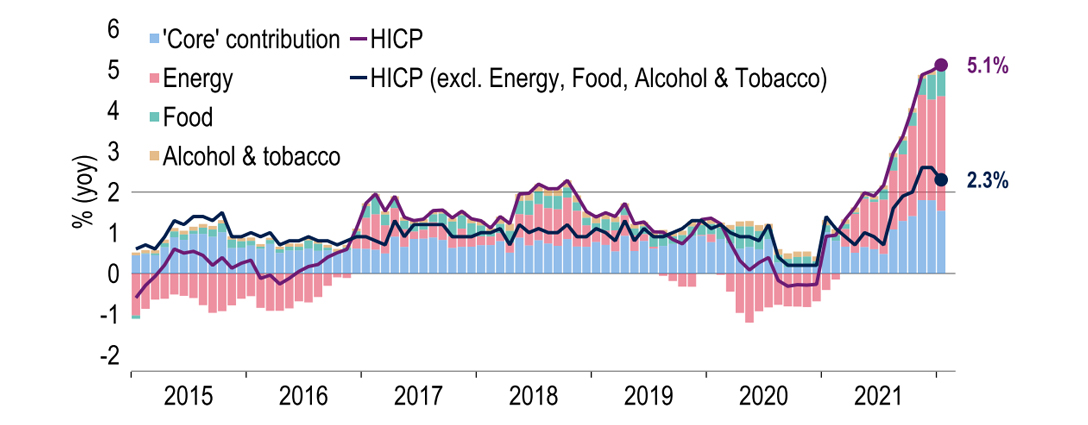

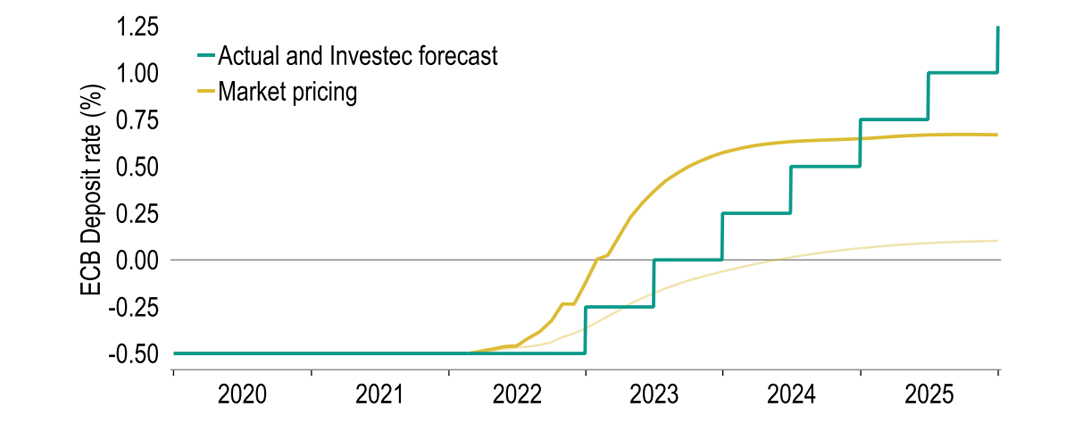

Inflation in the euro area started 2022 by rising to a new record high of +5.1%. Crucially, price pressures are broadening. With this in mind, European Central Bank (ECB) forecasts are once again due a big upgrade in March – the Harmonised Index of Consumer Prices (HICP) forecast for the first quarter of 2022 is +4.2%, far below our own estimate of +5.3%. It is on these ECB projections that prospects of rate increases will hinge. Base effects may mean that HICP fails to meet the target at the mid-point of ECB forecasts in March, which is a prerequisite for raising rates. However, we expect this condition to be met in September, paving the way for a December hike. This would be the ECB’s first hike since the days of former President Jean-Claude Trichet in 2011.

An important determinant of the inflation outlook is ultimately the labour market, which has recorded an impressive recovery. Notably, a host of indicators are back to, or even exceeding, pre-pandemic levels. The most prominent is the record low rate of unemployment at 7%. As a consequence, there are widespread reports of labour shortages, including a European Commission survey finding that a record number (25%) of industrial and services firms are facing output problems due to scarce labour. These tightening conditions should trigger a pick-up in earnings growth. This has yet to happen, with hourly earnings and negotiated wage growth still below pre-Covid levels. But we do not expect this pay restraint to continue indefinitely.

Chart 4: Eurozone inflation broadens out beyond just energy, with core contributions rising

Sources: Macrobond, Investec

Responding to the stronger-than-expected inflation outturns, the prospect of material upward revisions to its inflation projections come March and taking note of the strong labour market, the ECB struck a more hawkish tone at the last Governing Council meeting. Much store was set on these upcoming projections, but we see the groundwork laid for asset purchase programmes being scaled back more quickly than set out in December 2021. We now expect these to wrap up by September. At that point, the conditions the ECB has set for itself to start tightening could be met, signalling a first rate rise in December 2022, which we forecast to be a 25 basis point move to -0.25%. In 2023, we are looking for two further 25 basis point hikes.

It took the whole of 2018 for the ECB to reduce its €60bn monthly purchase pace to zero in January 2019.

Markets are, however, factoring in a more aggressive pace of tightening, including the prospect of deposit rate increases in the third and fourth quarters. We judge this to be too aggressive and not consistent with the gradual message being pushed by the ECB, nor with the tightening sequencing plan it has outlined. This is firmly stated to begin with the end of net asset purchases, followed by interest rates rises and then the end of QE re-investment. Assuming that the ECB leaves a short gap between the end of QE and the first rate hike – we do not believe the ECB would end QE and hike at the same meeting – a third quarter hike would require a much faster pace of tapering than in the past. It took the whole of 2018 for the ECB to reduce its €60bn monthly purchase pace to zero in January 2019.

Chart 5: Deposit rate pricing in 2022 and 2023 inconsistent with the ECB’s ‘gradual’ message?

Note: thinner, fainter line represents December market pricing

Sources: Macrobond, Investec

This prospective end to QE and rising rates has sent 10-year bund yields soaring to +24 basis points and contributed to a widening in peripheral spreads. We do not expect this to hinder normalisation, but it should support a gradual approach given a wish to avoid market fragmentation. Certainly, rising spreads are undesirable, but they are not at worrying levels and overall the cost of borrowing for countries such as Italy is still historically very low, averaging just 0.45% so far this year. Any comparison with the spread widening of 2012 is also undeserved, given a better economic and political backdrop. The latter is benefitting from the presidential election and Mario Draghi remaining as prime minister, aiding the continued reforms necessary for EU funding.

Broadly, we remain upbeat on the euro area’s prospects, our GDP forecasts standing at 4.1% for 2022 and 3.1% for 2023. The former is 0.3 percentage points lower than January, largely due to a weak fourth quarter in Germany and an expectation of negative growth in the first quarter. However, we look for a rebound in the second quarter. In terms of our market forecasts, we now foresee a greater rise in bund yields than previously, on account of monetary policy, and see 10-year yields standing at 0.75% for the fourth quarter of 2022 and 1.00% for the fourth quarter of 2023. We have also made some modest changes to our euro-dollar forecasts. Directionally, we still see the euro rising against the dollar over the medium term, but have tempered that rise to $1.18 by the fourth quarter of 2022 and $1.22 for the fourth quarter of 2023.

United Kingdom

Last month, the Office of Gas and Electricity Markets, Ofgem, decided on a 54% rise in the dual-fuel utility price cap from April. As anticipated, this was followed swiftly by the government announcing some mitigating measures to soften the blow for households. But these will only have a limited impact on CPI inflation: a £200 taxpayer funded zero-interest loan repayable over five years to lower each household’s electricity bill looks set to smooth the CPI inflation rise, but potentially only from October; it will also prolong the rise in inflation as the loan is repaid in instalments. And the £150 grants lowering council tax for those living in lower-banded homes ought not to impact CPI inflation, but cut CPIH, which includes owner occupiers' housing costs, and Retail Price Index inflation.

In our forecasts, we assume full mitigation of any further rise in utility bills through grants in October. With this, we now predict average inflation of 6.3% in 2022 and 2.3% in 2023, and core inflation of 4.2% and 2.3%. This will hurt consumer spending power and may constrain expenditure on non-essential items to some extent. But this is against a benign income outlook and upbeat savings backdrop. Higher wages given the tight labour market may absorb much of the hit to real incomes. Rising participation could fuel employment for a while too, also aiding incomes. In addition, the saving rate still has scope to fall. And even the roughly £20bn extra utility bill is dwarfed by about £159bn of excess savings amassed during the pandemic, which could be drawn on.

When analysing the results by income group, households with income over £100k accounted for more than a quarter of aggregate savings, despite making up only 7% of the population.

That said, UK household savings are not evenly distributed. A survey conducted by the BoE confirmed that higher income households hold the lion’s share of savings. When analysing the results by income group, households with income over £100k accounted for more than a quarter of aggregate savings, despite making up only 7% of the population. This suggests that, when faced with inflationary pressures, rate hikes and a national insurance increase in April, lower income households may not have access to the safety net of excess savings.

Taking this into account, and faced with prospects of somewhat higher inflation and policy rates than before, we have nudged down our forecast for GDP growth, by 0.3 percentage points to 4.2% for 2022 and by 0.2 percentage points to 2.2% for 2023. Both of these would still exceed average growth recorded in the decade prior to the pandemic. This follows from an already impressive economic recovery, with GDP at its pre-pandemic level as of November. That said, one quirk of the economic recovery has been the swings in healthcare output. At the onset of the pandemic, the sharp decline in face-to-face GP appointments resulted in healthcare output dragging on total gross value added (GVA). The introduction of Test and Trace and the vaccination programme reversed this, with 2021 seeing healthcare outperform. Excluding it, GVA would have been circa 1% below pre-pandemic levels in December.

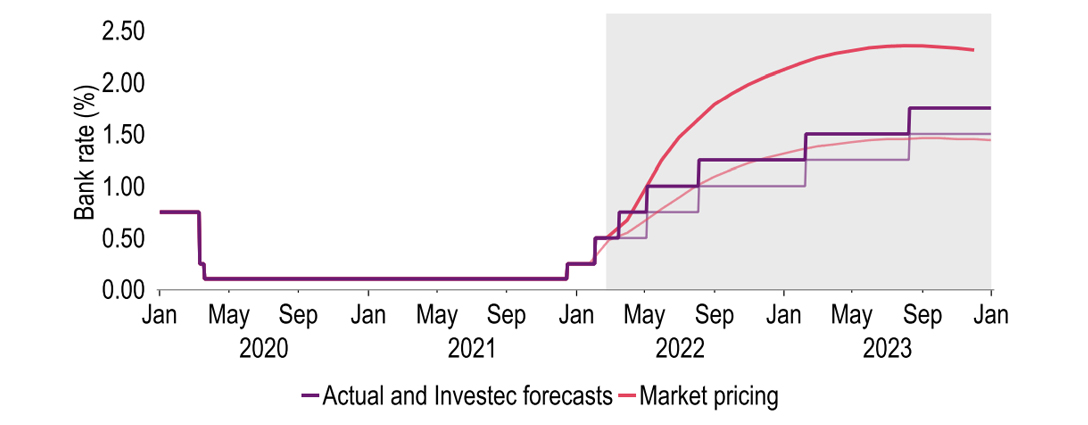

Chart 6: We anticipate further BoE rate hikes, but not as many as the market is now pricing in

Note: thinner, fainter lines represent January forecasts and market pricing

Sources: Macrobond, Investec

The BoE opted to hike rates by 25 basis points to 0.50% last month, marking the first back-to-back tightening since 2004. Although four of the nine Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) members backed a larger step of 50 basis points this time, the MPC signalled that the Bank rate may only need to rise to 1% to contain inflation. Underlying this was the judgement that second-round effects, where employees secure wage rises to compensate for higher inflation, in turn fuelling higher prices, will be avoided. We see somewhat more wage pressure than this and now expect three further 25 basis point hikes in March, May and August. This may not suffice to return inflation to target. But the MPC could pause to assess the impact of higher rates and balance sheet reduction before two further 25 basis point rate rises in 2023.

While we envisage an extra hike from the MPC, relative shifts in our Fed and ECB policy calls are larger – as such, we have lowered our GBP targets for the next two years. But on balance, we still expect the pound to strengthen. Sterling may also maintain or extend 2021’s gains against the euro if Brexit tensions ease. The confirmed early move to ‘living with Covid’ likely helped ease the pressure on the prime minister recently, but we see his political fate as having little effect on the currency. We now see cable at $1.42 for the end of 2022 – compared to our previous forecast of $1.48 – and $1.48 by the end of 2023 – versus $1.53 – with the euro-pound rate at 83p and 82p, respectively.

Chart 7: Sterling looks likely to gain over ’22 and ‘23, but US dollar to remain overvalued

Note: thinner, fainter lines represent January forecasts

Sources: Macrobond, Investec

Get more FX market insights

Stay up to date with our FX insights hub, where our dedicated experts help provide the knowledge to navigate the currency markets.

Browse articles in

Please note: the content on this page is provided for information purposes only and should not be construed as an offer, or a solicitation of an offer, to buy or sell financial instruments. This content does not constitute a personal recommendation and is not investment advice.