2023 looks likely to be a challenging year for the major developed markets, all of which look set to enter (shallow) recessions under the weight of higher interest rates and – in Europe in particular – higher energy prices.

Higher rates, however, are not an accident but a bitter medicine that central banks have dispensed in abundance during 2022 to help bring inflation, at multi-decade highs everywhere, back under control. We expect that next year this will bear fruit. Taking into account the lags with which changes in monetary policy act (which vary, but are typically expected to be a year or so), it is in 2023 that the drag on demand is likely to spread from the most interest-sensitive parts of the economy, such as housing, to wider conditions including the labour market. Besides job losses, extra rebounds in labour force participation may also contribute to dampening momentum in wages and break the cycle that risks above-target inflation becoming entrenched. A further inflation-busting factor could be ongoing easing in supply chain disruptions if China gradually moves away from its zero-Covid policy.

Even then, we do not expect target inflation to be hit by end-2023 as yet, but the trajectory ought to point firmly downwards. This, in our view, will allow central banks to start to back off from their restrictive stance later in the year. But QT may nevertheless continue, limiting falls in yields.

Key calls for 2023

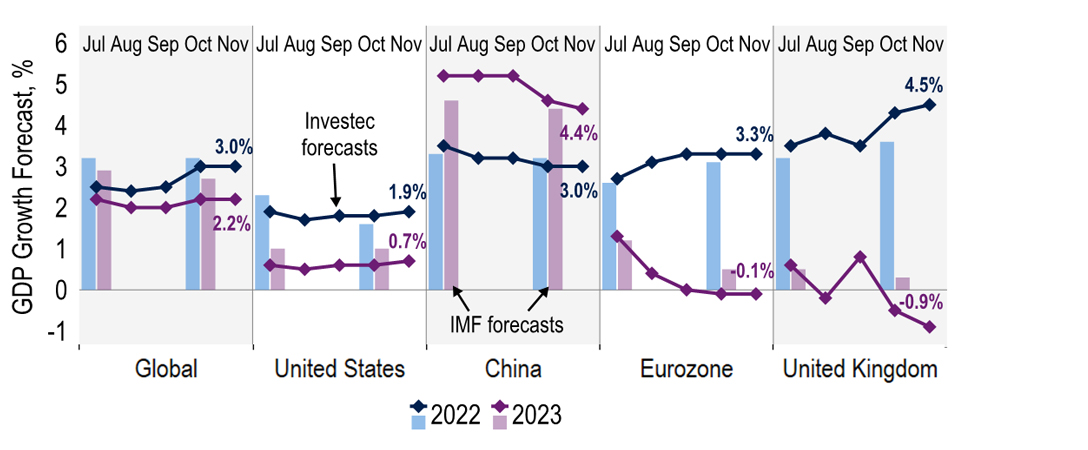

- Recessions in the major developed markets, but shallow ones. We are looking for global growth of 2.2% in 2023, down from 3.0% in 2022. Fiscal support to households and firms to deal with energy prices will limit the downturns, and the financial system looks in better shape than in deeper and more prolonged recessions (e.g. GFC and euro crisis).

- China bucks the trend. Chinese authorities’ strict zero-Covid policies will be eased gradually. Along with measures to alleviate the property crunch and accommodative policy, growth could recover next year.

- Sharp slowdowns in inflation even if not quite to target. Inflation is currently at its peak or near it across the major jurisdictions. Price pressures will fade as recessions loosen labour markets and energy price rises no longer match 2022’s astronomic pace, or even start to slip.

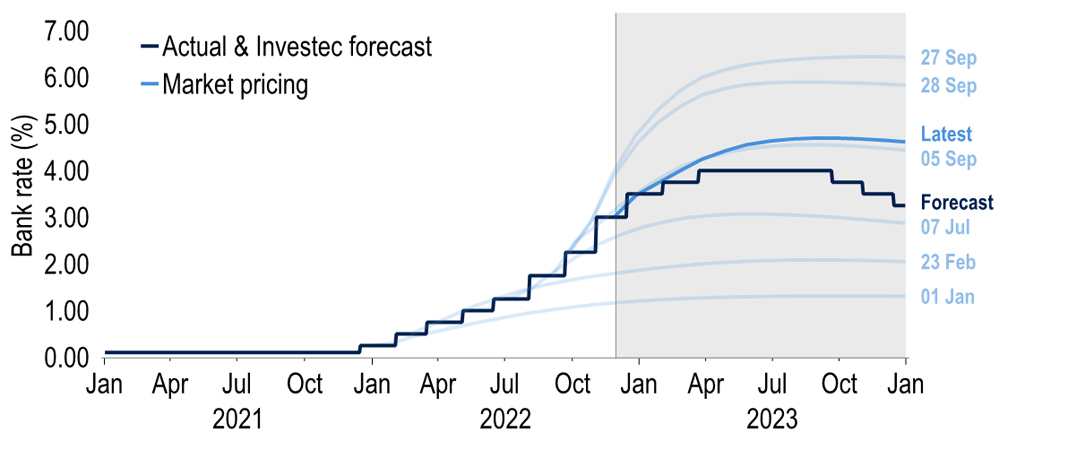

- Monetary policy starts to reverse course. Further, if slower, rate hikes are likely into early 2023. The BoE may be the first major central bank to start cutting rates, but the Fed and the ECB may follow by year-end.

- Bond yields move down from here. As market expectations for central bank ‘terminal rates’ slip, so will longer-dated bond yields. But a return to their pre-pandemic lows looks highly unlikely.

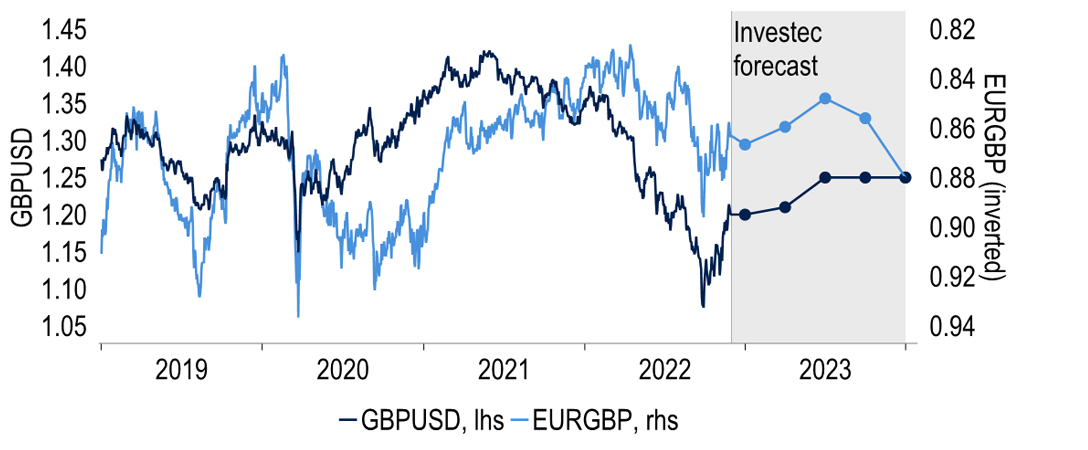

- USD strength could fade with rate differentials. The support USD has received from terms-of-trade effects (due to higher gas prices) may remain, but interest rate differentials have scope to fall, prospects of which lead the dollar lower. Sterling benefits early in the year but the UK’s relatively weak growth outlook stalls the rebound against USD later on.

Global

After three decades of largely subdued global price pressures, 2022 was a year when the strength, breadth and persistence of inflation returned with a vengeance. Central banks eventually responded by raising policy rates more aggressively and in some cases started to unwind QE, allowing their balance sheets to contract. Global bond markets have been volatile, not least given huge repricing at the shorter end of yield curves. Given the considerable degree of monetary tightening that has now taken place and an ensuing period of softer global growth, we are likely to be at or very close to peak inflation in developed markets (DMs).

Labour shortages are aggravating the situation in DMs, fuelled in many cases by falling participation rates. The precise reasons for shrinking labour forces are not 100% clear, but seem to include; ill health (as hospitals cope with Covid backlogs); a switch in work/life balance preferences; early retirement (especially when asset markets were more buoyant and boosting pension values); and a rise in students. A key judgement is that we expect participation to recover. Many health issues (we hope) should be resolved in time and a harsher economic climate may encourage many to return to work. A danger though is that workers become deskilled if they are away from employment for too long.

Supply chain issues have also dogged the world economy, not least due to China’s zero Covid policy. Why has Beijing maintained this stance when its economy is struggling? China’s total vaccination rates are high, but those for the elderly are relatively low – at least a third of over 80s have yet to receive a booster jab. This is critical as various studies suggest that China’s CoronaVac and Sinovac vaccines are less effective than western alternatives, unless top up boosters are given. Global supply chain strains seem to have eased in recent months, and China’s lockdown stance will be a determining factor on whether this direction is maintained over 2023. Our guess is that a vaccination drive will reinforce what already seems like a gradual relaxation of its Covid laws.

Another ongoing geopolitical issue is the war in Ukraine. The Ukrainians have regained ground in the east and south of the country, while the threat of Russian deployment of nuclear weapons has dissipated. But there is still a big question mark over Putin’s endgame, and so the conflict will likely continue to cloud the outlook in 2023. In addition to the primary humanitarian consequences, the global food & energy outlooks remain severely disrupted, with Russia a huge net energy exporter and Ukraine the world’s breadbasket. A key focus for 2023 may well once again be the extent to which alternative energy supplies can be secured ahead of the 2023/24 winter.

Chart 1: Global growth to slow in 2023 as advanced economies see recessions

Sources: IMF, Macrobond and Investec

We see few reasons to alter our existing view of 2023 prospects. The various headwinds, especially tighter monetary conditions, pull global GDP growth down to 2.2% from 3.0%, with much of the DM space in recession. An exception to the trend is China, where growth steps up to 4.4% from 3.0%, helped by a new booster vaccination drive, greater tolerance of Covid cases and fewer lockdowns. This also helps to reduce logjams in global supply chains, albeit gradually. Also, labour market strains ease, partly due to layoffs, but also as participation improves. This helps inflation to retreat from double digit levels in many jurisdictions.

Our assessment is that spare capacity will build sufficiently for central banks to be back on track to meet their inflation targets. In some areas, e.g. US & UK, central banks should be able to begin to bring rates down by end-2023. Indeed, we continue to view yield curves to be too steep. One question is whether major central banks persist in reducing their balance sheets through 2023, perhaps even after beginning to cut policy rates. We note that unlike 2008/2009, banks are functioning properly, so that as central banks cut rates when inflation pressures are sufficiently under control, demand will recover. But we stress that adequate labour market and supply chain capacity are critical, so that higher demand turns into growth and not inflation. If not, central banks’ ability to stimulate the world economy will remain limited.

United States

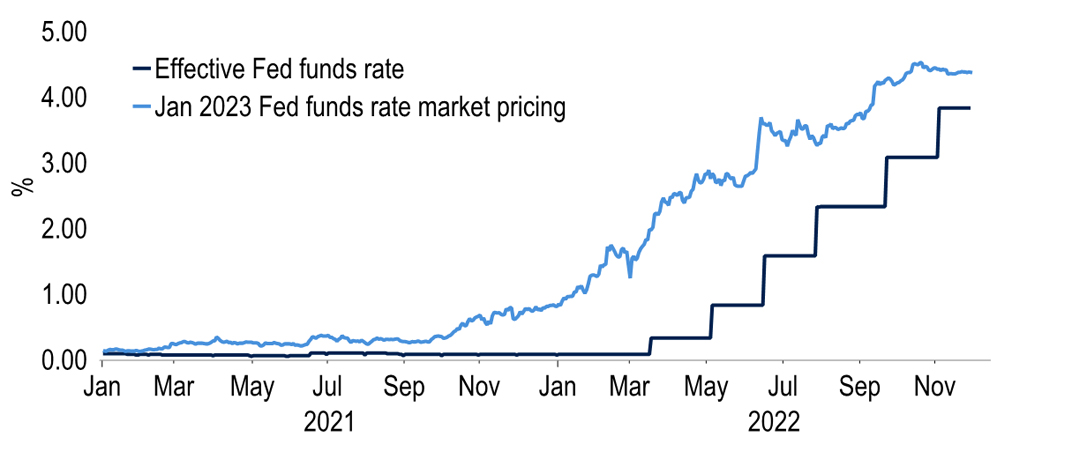

2022 has been a year defined by aggressive rises in interest rates, particularly by the Federal Reserve. Inflation has proved harsher and more persistent than expected, while the labour market has remained incredibly tight. Both factors have forced the FOMC to raise rates both further and faster than markets imagined until recently. The Fed’s actions have also contributed to a dominant year for the USD, which has additionally benefitted from the US’s terms of trade gains as a net exporter of gas. Now that rates are ‘restrictive’, the dollar is very sensitive to US economic data as the market looks for any sign of a pivot from the Federal Reserve.

Chart 2: The rapid, and for a long time underestimated, rise in policy rates over 2022

Note: The Jan 2023 future proxies for the end-2022 expectation

Sources: Bloomberg, Macrobond, Investec

In 2023 these signs should become clear as inflation pressures ease markedly. The lagged effect of the Fed’s tightening should bear down on inflation, helped by markdowns due to high inventory levels as well as base effects. For the latter, the mantra of ‘what goes up, must come down’ rings true. Prices do not even need to fall for inflation to decline; if prices remained flat over the next year, inflation would decline rapidly. Zero price growth is unlikely, but even the modest monthly price growth that was typical pre-pandemic, would pull down on inflation due to helpful base effects. This downward trend in inflation, on top of a slowing economy will, in our view, allow the Fed to pause rate hikes by end-Q1.

One risk to this view would be that labour market tightness persists, placing upward pressure on wages. Our base case is, however, that the labour market will soon start to struggle amid weaker activity and that unemployment will rise from the current extremely low starting level. A potential leading sign of that is an easing in hiring intentions. We do not see the unemployment rate reaching that of previous downturns, though. One reason for that is the subdued participation rate. Neither an easing of Covid rules nor high wages amid rising inflation have so far enticed as many workers back to the labour market as pre-pandemic. Although we envisage that eventually participation will fully recover, this may take time.

For now, with subdued participation, yet robust labour demand, the labour market is heading into the economic downturn from a strong base. But with other sectors of the economy clearly struggling under sharply higher interest rates, such as the housing market, we think the relative resilience of the labour market will merely cushion a recession next year rather than prevent it. We maintain our call for a short, mild recession in H2 2023 and for the Fed to subsequently cut rates to support the economy. Rate cuts are likely to extend throughout 2024 as the policy rate journeys back to neutral. Even so, QT is expected to continue until the balance sheet has shrunk sufficiently.

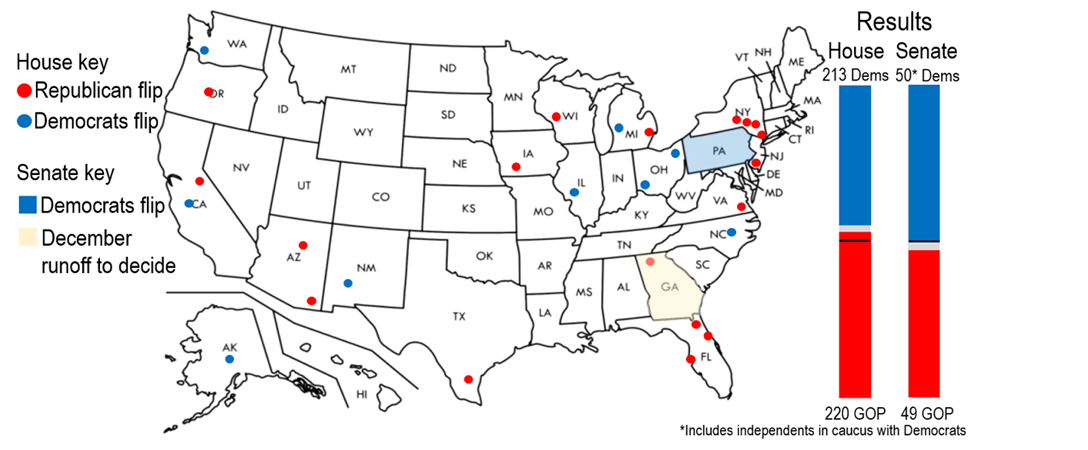

Chart 3: Red wave fails to materialise at US midterms

Sources: Investec, Politico results tracker

Monetary policy is not the only focus; politics is also taking centre stage. Historically US midterm elections are difficult for the incumbent party and President Biden approached the midterms with a very low approval rating. Yet predictions of a red wave turned out to be overstated. The Democrats managed to cling onto control of the Senate, possibly even gaining a seat depending on the results of the Georgia senate runoff race on 6 Dec. As was expected the Republicans took control of the House, but only very narrowly. This stalemate makes any real change from the current status quo unlikely.

One thing that the Republicans are likely to do however is launch potentially bruising investigations into the President and his family ahead of the 2024 elections. Given his age and unconvincing polling, there are suggestions though that Biden may not run for another term. If so, CA Governor Gavin Newsom or Transport Secretary Pete Buttigieg look to be the favourites for the presidential nomination, although Newsom has thus far ruled out running. The definitive list of runners and riders should become clear next year. For the Republicans, it is all about Trump vs FL Governor DeSantis. Both run similar platforms, arguing against the ‘woke’ agenda – DeSantis was once Trump’s poster child. Yet a poor midterm performance for Trump-backed candidates against DeSantis’s success in his Governor race has turned the odds in DeSantis’ favour as of late.

Eurozone

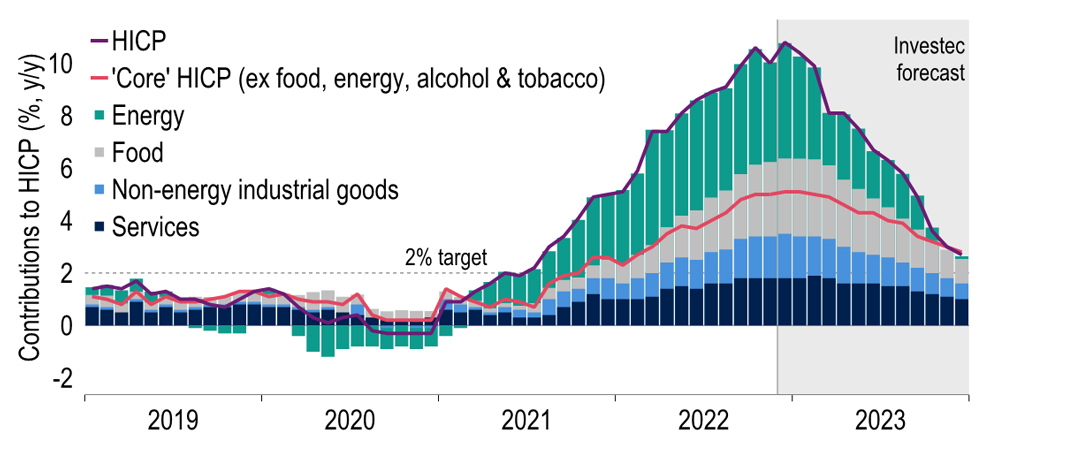

As elsewhere the inflation outlook is a key question for 2023 in the Euro area. November saw HICP soften to 10%, and core hold at 5%. It may still be premature to declare the peak, but there are some incipient signs of inflation perhaps abating: survey data from the PMIs for example have recorded two consecutive months of easing price pressures. We continue to expect a moderation in 2023 as energy and food’s influence fades. Tighter policy, softening demand and easing supply chain issues will likely also play a part. Risks to this view are to the upside, energy being one key factor, the labour market and wages another. But whilst wage growth has risen, it has not been inflation-busting. For example, Germany’s largest union’s latest pay deal was a below-inflation 5.2% uplift.

Chart 4: Inflationary pressures are expected to ease in 2023

Sources: Macrobond and Investec

This backdrop will see the ECB maintain a hawkish bias at least in the near term. We expect further rate rises, albeit at a reduced pace of 50bps in December and 25bps in February, taking the Deposit rate to 2.25%. There is a risk that rates could rise a little further than this, but our base case of a recession envisages a pause at 2.25% and a small easing in late 2023. December’s ECB meeting may provide a little more clarity given updated macro forecasts, which should see the outlook downgraded. This was acknowledged in October’s meeting account, which noted a recession was becoming the baseline, and further highlighted by the ECB’s Financial Stability Review (FSR) which put an 80% probability on it. Clearly the clouds are gathering over the 2023 outlook given a multitude of headwinds: the cost-of-living is weighing on demand, energy remains a concern despite recent positive developments, whilst tighter financial conditions stemming from ECB policy and a global slowdown will all have an impact.

We continue to forecast a double dip, starting with a recession this winter and ending in H2 2023, with a peak-to-trough GDP fall of 0.7%. On an annual basis our forecasts are unchanged at 3.3% 2022 and -0.1% 2023. The risk of a deeper downturn, where energy prices play a greater part is set to be mitigated to some degree by fiscal easing in various countries.

From a market perspective QT, which we expect to start in April, is something to watch out for. Thus far rates have been the main policy lever, but attention is turning to the ECB’s balance sheet given that it sits at odds with tighter policy. But an additional consideration is a scarcity of core sovereign bonds available for use as collateral in repo operations. The ECB’s holdings under QE are a large factor, a shrinkage of which would hence help to address the issue. As an example, we estimate that only 28% of outstanding German government bonds are available to the market (free-float). A point that we would also make here is that we judge the desire to shrink the balance sheet to be sufficiently strong for the ECB to conduct QT even when it cuts rates, as we expect late next year.

A possible widening in yield spreads and fragmentation risk in the more indebted EU19 states will be a risk that needs to be monitored by the ECB as a trade-off associated with QT. Other risks to consider in 2023 include energy. Whilst recent developments have been positive with gas storage levels ahead of target and the winter being mild so far, there remain risks to the energy picture next winter. With Russian supply still heavily restricted, Europe may have difficulty refilling storage next summer, especially if China begins to recover, drawing in more supply itself. This is a situation which could foster a deeper downturn in H2 2023, but that is not our base case.

Some retracement of dollar strength has seen EURUSD re-establish its positioning above parity. The pair climbed to its highest since July, almost touching $1.05. As Europe gets closer to resolving its energy crisis some of the terms-of-trade drag on the EUR should subside, while interest rate differentials should also provide support. With ECB rates not becoming very restrictive in the first place, subsequent policy easing is likely to be less than in the US and UK. Hence, we see EUR strengthen further through 2023, to $1.10 against USD and 88p against sterling. In the same vein, we would expect that trend to continue for the common currency through 2024.

United Kingdom

After two years of upside surprises, in which inflation surged from 0.3% to a four-decade high of 11.1%, it seems bold to suggest inflation is now at its peak and set to fall markedly. Yet this is what we anticipate. A key factor is the extension of the Energy Price Guarantee for the year from Apr ’23, albeit at a higher £3,000, which locks in a diminishing contribution from energy to inflation. It is also plausible that the momentum in food prices will ease, judging by futures prices for soft commodities. More fundamentally though, our view is predicated on recession leading to a rise in unemployment and with it reduced wage pressure. We have cut our UK GDP growth forecast from -0.5% to -0.9% for 2023, now expecting quarterly falls in GDP for Q1 to Q4.

Incorporating this, we expect CPI inflation of 3.7% by end-2023. A key constraint to GDP is fiscal policy. The Autumn Statement budgeted substantial (£83.4bn) support to limit the surge in energy bills for households and firms in FYs2022-24. Even so, the OECD reckons there will be only a minor loosening in the overall fiscal stance next year, the swing in the underlying primary balance being just -0.2%pts. This will not suffice to offset the fall in real disposable incomes for households. The reality for Chancellor Hunt is that sharply higher inflation and yields across the curve mean more fiscal revenue is absorbed by debt servicing, and markets have made clear their dislike for more borrowing. Indeed, the fiscal stance will be tightened clearly from 2024.

With the government tightening the fiscal screws, the need for the BoE to slam on the brakes through monetary tightening is reduced. We see a peak Bank rate of 4%, somewhat less than the market. Moreover, we anticipate recession will lift unemployment to 4.8% by Q4 2023. This looser labour market would give scope for the MPC to reverse some of their recent hikes. By end-’23 we see Bank rate back at 3.25%, with the direction of travel being to temporarily below ‘neutral’ during 2024.

Chart 5: UK Bank rate expectations have receded markedly but still look too high to us

Sources: Macrobond and Investec

Even so, the higher level of interest rates stands to have a material impact on the UK housing market, despite the share of variable-rate mortgages having shrunk considerably over time (now just 14% vs 50% in Q1 2016). After all, UK mortgages tend to be fixed for fairly short periods – typically two or five years, vs 30 years in the US. Hence c.21% of mortgages will have to be refinanced in 2023, after 7% in H2 2022, at much higher rates than before. This adds an extra headwind to house prices, on top of that from rising unemployment. We factor in a nominal 7% peak-to-through fall in national house prices. This may seem modest, but relative to consumer prices and wages, the adjustment is larger.

Sterling’s recovery from its credibility loss post ‘mini’-Budget has continued. Combined with some dollar weakness, this has seen cable rise above the $1.20 handle for the first time since August. GBPUSD has scope for further gains over H1 2023. But if the Bank rate then falls considerably short of what is priced in and the growth backdrop for the UK is materially weaker, that poses a risk to the pound beyond that. A likely simultaneously softer dollar means we see cable as fairly rangebound over H2 next year, at $1.25, with the risk that the dollar retains its strength. But we expect falls against the euro, to 88p by the end of next year and perhaps further in 2024.

Chart 6: Sterling to lose ground against the euro in H2 2023

Sources: Macrobond and Investec

As the third Prime Minister in a year, following political turmoil, Rishi Sunak faces an uphill battle to secure a win for the Conservative party at the next general election: the Tories lag far behind in polls, and recession stands to limit room for pre-election giveaways. But Chancellor Hunt has restored confidence in gilt markets, despite delaying the bulk of planned fiscal consolidation until after the election. Were recent falls in interest rates & energy prices sustained, there may even be some scope for looser policy. But whoever wins will remain constrained by market discipline – including Labour under Keir Starmer, whose policy leanings look in any case much more centrist than those previously under Jeremy Corbyn.

Get more FX market insights

Stay up to date with our FX insights hub, where our dedicated experts help provide the knowledge to navigate the currency markets.

Browse articles in

Please note: the content on this page is provided for information purposes only and should not be construed as an offer, or a solicitation of an offer, to buy or sell financial instruments. This content does not constitute a personal recommendation and is not investment advice.