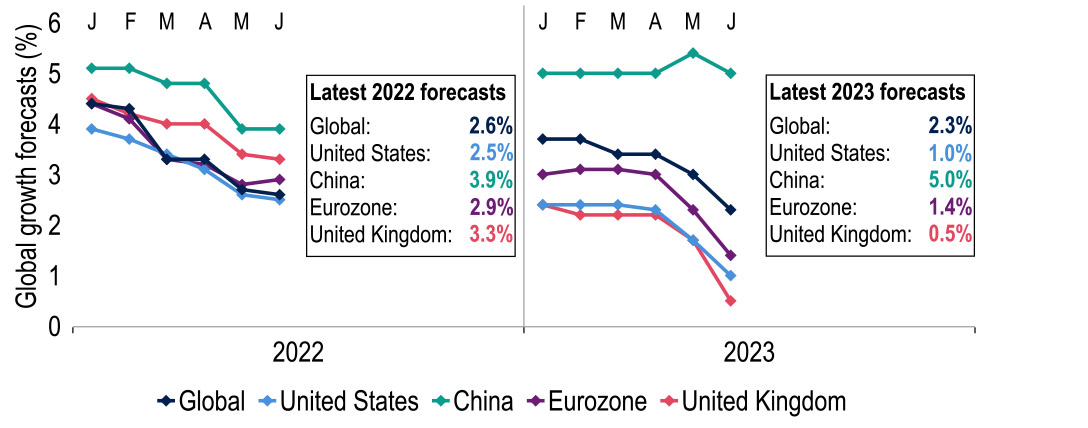

Unnerved by rising inflation expectations, central banks – led by the US Federal Reserve – have signalled a shift in their ‘reaction function’: now judging restrictive rates as required to bring inflation to heel. Technical recessions – in some cases – and weaker labour markets appear increasingly tolerated as the price to pay for achieving this goal. As well as pencilling in higher rates in the near term, we have cut our global gross domestic product (GDP) growth forecasts, by 0.1 percentage point to 2.6% for 2022 and by a heftier 0.7 percentage point to 2.3% for 2023. Financial markets have not taken kindly to such prospects. This, in turn, may aid a swifter cooling in ‘core’ inflation. Ultimately, we see not only a lower rate peak than markets but also rate cuts in mid-2023, in the US and the UK.

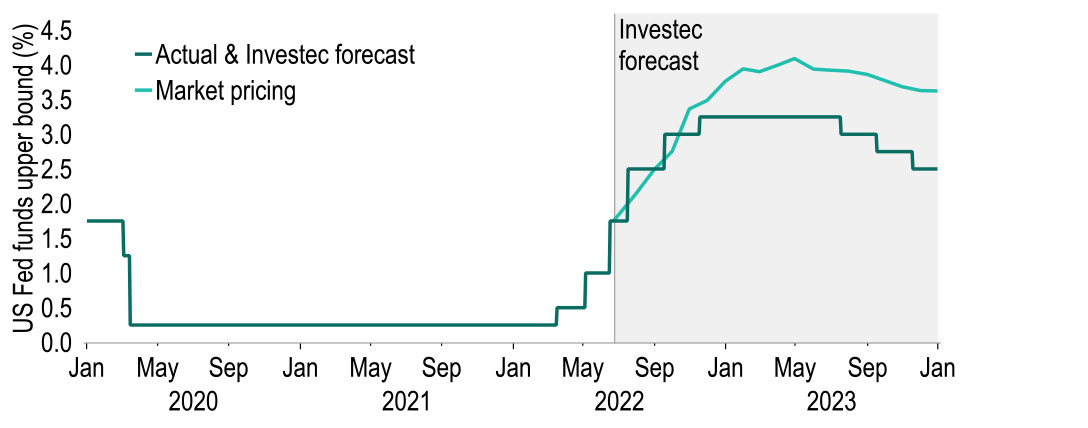

The Federal Open Market Committee’s (FOMC) 75 basis point hike in the Fed funds target to 1.50-1.75% came on the back of a poor Consumer Price Index (CPI) figure and worrying data on inflation expectations. Fed projections now envisage the funds target to be 3.75‑4.00% by end-2023, accompanied by modest GDP growth and a shallow rise in unemployment. The economy would be fortunate to escape with such a ‘softish landing’. While the Fed’s ‘frontloading’ looks set to continue for now, we envisage a peak in rates of 3.00-3.25%. But with quantitative tightening (QT) adding to the restrictiveness of the overall policy stance, we view a mild recession to be likelier than not next year. If so, modest easing should follow in the second half, provided there is a clear improvement in the inflation outlook.

The European Central Bank (ECB) has also turned more hawkish amidst increasing concerns over inflation. As such, we see a more aggressive frontloading of policy, with the deposit rate rising to 0.75% by the end of this year. However economic headwinds are rising, and we believe sufficiently so for the ECB to pause normalisation over 2023. Our central view is that the EU19 avoids a recession but sees subdued growth, with our forecasts revised lower to 2.9% for 2022 and 1.4% for 2023. The big risk to this view lies with the energy situation and the threat of gas shortages over the winter. However, the ECB will also need to walk a very fine line between raising rates and preventing fragmentation risks, given widening sovereign spreads, but we believe it has the tools – including new ones – to head off debt concerns.

The Bank of England has hiked the bank rate successively in the past five meetings in an attempt to rein in spiralling inflationary pressures. We expect this tightening cycle to continue in the short term, now pencilling in three more 25 basis point rate rises this year, resulting in the bank rate peaking at 2.0%. From here, we expect the economy to struggle under the weight of higher interest rates and to enter a short recessionary period at the end of the year, extending into Q1 2023. We believe this outcome would force a policy pause from the Monetary Policy Committee (MPC), while the inflation outlook is assessed against a weaker economic backdrop. Once the medium-term danger from inflation pressures starts to subside, we envisage the MPC will cut rates in mid-2023 to support economic growth. Accordingly, our end-2023 bank rate forecast is now 1.25% and we look for 2023 GDP growth of 0.5%, compared with 1.7% previously.

Global

There has been a major change in tune by central banks this month, led by the FOMC: it now expects policy rates will need to become firmly restrictive in the near term to achieve similar inflation rates in 2023 to those predicted in March, despite unemployment rising somewhat. We regard this as a change in the central bank’s ‘reaction function’, triggered by its determination to clamp down on inflation expectations. Unnervingly, these have shown signs of rising in tandem with the current surge in prices. Similar considerations seem to be behind the ECB’s signal of faster tightening, as well as the surprise 50 basis point hike in Switzerland and large back-to-back rate rises in India.

Arguably, a larger share of US inflation seems demand-driven, at least relative to Europe, where supply disruptions induced by the war in Ukraine appear to be playing a somewhat greater role. This explains the comparatively aggressive stance taken by the Fed. US policy is now being tightened through both policy rate rises and exchange rate appreciation, as illustrated by a Monetary Conditions Index combining the two. In contrast to their central banks lagging in tightening resolve, the euro and pound have weakened in trade-weighted terms. This counteracts some of the move to higher interest rates and therefore blunts their impact in reducing inflation pressures – adding to the pressure to be more forceful on rates.

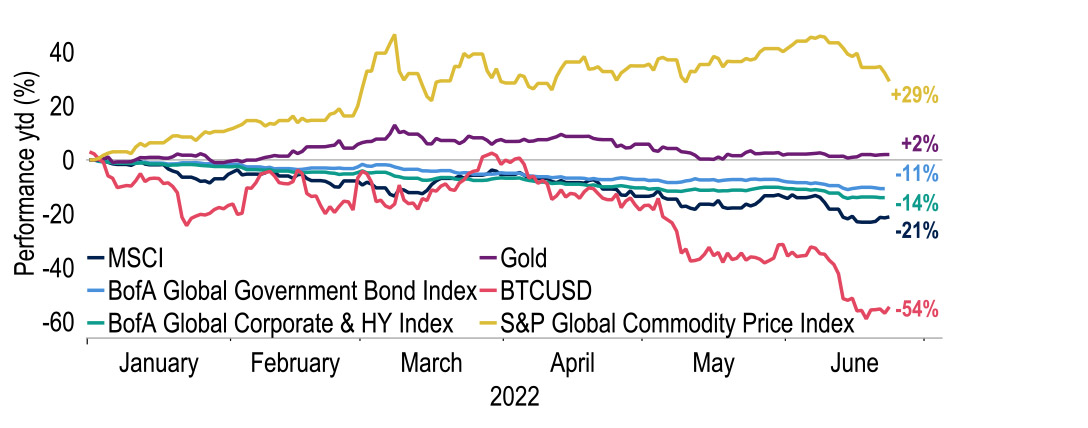

Certainly, government bond markets did not take kindly to the shift in reaction function by the Fed, recording a sharp acceleration in sell-off across the curve. As this was reflected in swap rates, pressures are for further mortgage rate rises. And coupled with the widening in corporate spreads, especially for high yield issuers, firms’ borrowing costs are up too. Moreover, it proved the final straw and tipped US stock markets into ‘bear market’ territory, typically defined as a 20% fall in a broad index from its peak. The significance of the latter should perhaps not be overplayed, seeing as, relative to pre-Covid levels, equity markets are in fact still higher.

Chart 1: Stocks and bonds (& cryptocurrencies) have sold off sharply since the start of the year

Sources: Macrobond, Refinitiv, Investec

Nevertheless, the sharp tightening in financial conditions has raised the odds of recession. In fact, our latest estimates now incorporate technical recessions in both the UK and the US. This is reflected more widely and, as such, our world growth forecasts are reduced once again. We now predict growth of 2.6% in 2022 and 2.3% next year, compared with 2.7% and 3.0% previously. But key to note is that this is not a balance sheet recession driven by a financial collapse. In that sense, the downturn should be a fraction of that of the 2008 global financial crisis and also a long way from Covid-19. Further, in raising rates, most central banks will have created room to manoeuvre to assist ailing economies. Even so, a recession is still a recession.

Chart 2: Investec growth forecasts downgraded as recessions loom for key economies

Sources: Macrobond, Investec

The silver lining of this weaker outlook for activity is that, by opening up spare capacity, wages and ‘core’ price pressures ought to diminish. Typically, labour participation is pro-cyclical, in the sense that tighter labour markets entice more people to search for jobs, and vice versa. However, in the current context where surging stock market wealth had encouraged some people to bring forward retirement plans, especially in the US, the sharp fall that has already taken place in equity markets might encourage a countercyclical rebound in labour force participation instead, alleviating labour market tightness further.

A period of ‘stagflation’ at the global level may well ensue during the course of 2023.

In time – on our current projections, in mid-2023 – this may open up scope for rate cuts in countries where monetary policy should by then have become contractionary, such as the US and the UK. Still, it will take some time for overall inflation to subside to target levels. After all, rolling lockdowns under China’s zero-Covid policy put ongoing pressure on supply chains. And commodity price pressures related to the war in Ukraine show little signs of abating. Indeed, Russia has tightened the screws in terms of restricting gas flows to Europe, sending prices higher; and wheat prices remain extremely high. This may harm poorer nations disproportionately. A period of ‘stagflation’ at the global level may well ensue during the course of 2023.

United States

Having guided towards 50 basis point hikes for June and July, the FOMC lifted the Fed funds target range by 75 basis points to 1.50-1.75% on 15 June. It is now signalling a 75 or 50 basis point hike in July. The new dot plot shows a median funds target of 3.25-3.50% by end-2022 and 3.75-4.00% by end-2023, the latter 100 basis points above its March projections. Despite the aggressive tightening, the committee still sees the economy expanding. GDP is forecast to grow at an annual rate of 1.7% over the next two years and unemployment to rise only modestly to 4.1% by end-2024, from 3.6% now. To us, this looks like a hopeful Goldilocks scenario. Indeed, others have labelled it as ‘remarkably optimistic’ and the ‘immaculate disinflation’.

The Fed’s sudden hawkish pivot came about from last minute CPI and inflation expectations data. May’s annual CPI rate rose to 8.6% from 8.3%, confounding the view that inflation had peaked, although the core number did slip back to 6.0% from 6.2%. But the University of Michigan data showed 5-to-10-year inflation expectations at 3.3%, which, an inflation spike in 2008 aside, represents a 25-year high. Inflation expectations tend to matter more when labour markets are tight. Such conditions give rise to a heightened risk of an acceleration in pay and of entrenched high inflation over the medium term. This explains what we would label as a shift in the FOMC’s reaction function.

Any recession would be worlds apart from 2008/9 when the global financial system collapsed.

But the sharp acceleration in pay growth that the Fed so fears is yet to be shown in the data. In fact, three month annualised hourly earnings growth is now at its lowest in twelve months. The Employment Cost Index (ECI) is king among the wage growth measures, however, and as yet has been inconclusive – the Q2 ECI is due for release on 29 July, two days after the Fed meeting. The FOMC will hope a continued recovery in the participation rate can help alleviate some wage pressure – at 62.3% there is still some ground to make up compared to the February 2020 rate of 63.4%. One avenue could be a reversal of the ‘great retirement’, as pension pots will have suffered of late in the wake of falling stock and bond prices.

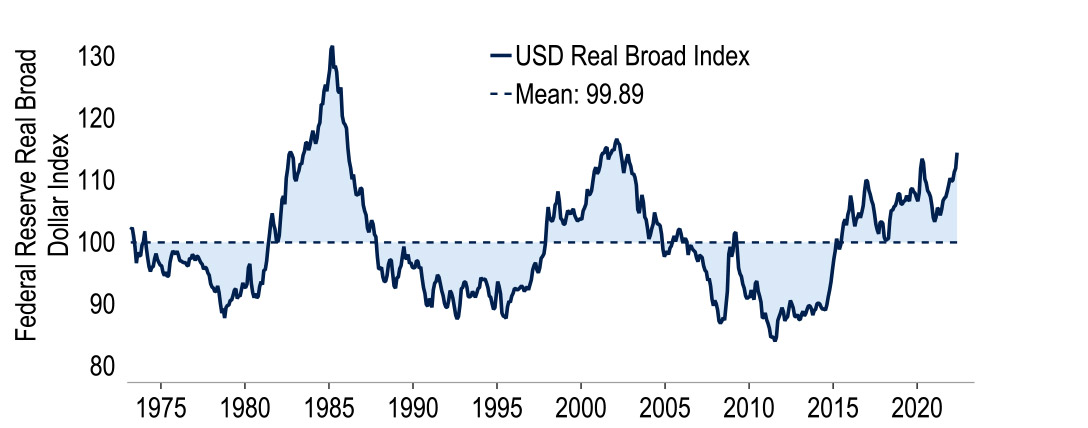

A pervading consequence of the current geopolitical uncertainty, aversion to risk assets and Fed tightening has of course been the strength of the dollar. Indeed, the Fed’s nominal trade weighted index is some 5% higher so far this year. Its real index has soared too and is well above its long-term average, loosely implying a degree of overvaluation of around 14% in purchasing power parity terms. The relatively closed nature of the US economy means that activity and inflation trends tend to be less sensitive to movements in the exchange rate than its counterparts in Europe and Asia. Overall, we give the dollar relatively little weight in our US monetary policy assessments.

Chart 3: The Fed’s Real Broad Index points to a 14% overvaluation of the USD

Sources: Macrobond, Investec

Indeed, the FOMC is set to continue stepping hard on the brakes for a while longer. A second 75 basis point hike looks likelier than not next month and we are looking for 50 and 25 basis point moves in September and November, taking the target range to 3.00-3.25%. $95bn per month of QT due in September may be the equivalent of a total policy rate increase of 50 basis points, leaving clear blue water between the policy stance and the Fed’s estimate of a neutral rate of 2.5%. Although not as aggressive as the recent dot plot, the economy would be highly fortunate to escape with a ‘softish landing’. We envisage the economy entering a mild technical recession in mid-2023, prompting the FOMC to cut rates by a total of 75 basis points to 2.25%-2.50% in H2 next year.

Chart 4: The Fed will pause tightening and start easing earlier than the market thinks

Sources: Macrobond, Investec

Our GDP forecasts are now 2.5% for this year and 1.0% for 2023, compared with 2.6% and 1.7% previously. We have three further points to make. First, any recession would be worlds apart from 2008/9 when the global financial system collapsed. Recoveries from ‘cyclical’ recessions are more straightforward to deal with by easing policy. Second, the Fed would no doubt opt to stop QT while it is cutting rates, shifting it towards a still looser policy stance. Third, we have argued for some time that the curve is too steep. Recently, markets have priced out a 4% peak for the funds target and 10-year Treasury yields have eased back from 11-year highs of 3.50%. Our rate view is consistent with a continuation of this trend leading to 10-year yields of 2.50% by end-2023.

Eurozone

June’s ECB meeting confirmed what many had expected, with a clear steer that rates are set to rise in July, via a 25 basis point hike in all the key rates. However, as elsewhere, tolerance of high inflation is waning and will see the ECB frontload policy more aggressively than previously anticipated. This we expect to be in the form of a 50 basis point deposit rate hike in September, accompanied by changes in the other key rates to return to a symmetrical rate corridor. We also see 25 basis point moves at the remaining meetings this year, talking the deposit rate to 0.75% by end-2022. Driving the change in tone to consider 50 basis point hikes is inflation, which has consistently been worse than expected.

Tolerance of high inflation is waning and will see the ECB frontload policy more aggressively than previously anticipated.

May’s Harmonised Index of Consumer Prices (HICP) reached another record high at 8.1%. At the same time, price pressures are broadening, with 75% of items above 2%. Signs of an adjustment in inflation expectations have further fuelled ECB concerns, particularly with regards to possible second round effects. Although the idea of a wage-price spiral has been dismissed, the tone has changed with President Lagarde noting that wages had picked up since March: Q1 compensation per employee was recorded at 4.4%, whilst negotiated wages rose 2.8%. Given the tightness in the labour market, the ECB fears a further pickup. For example, Germany’s largest union, IG Metall, is calling for a 7-8% rise.

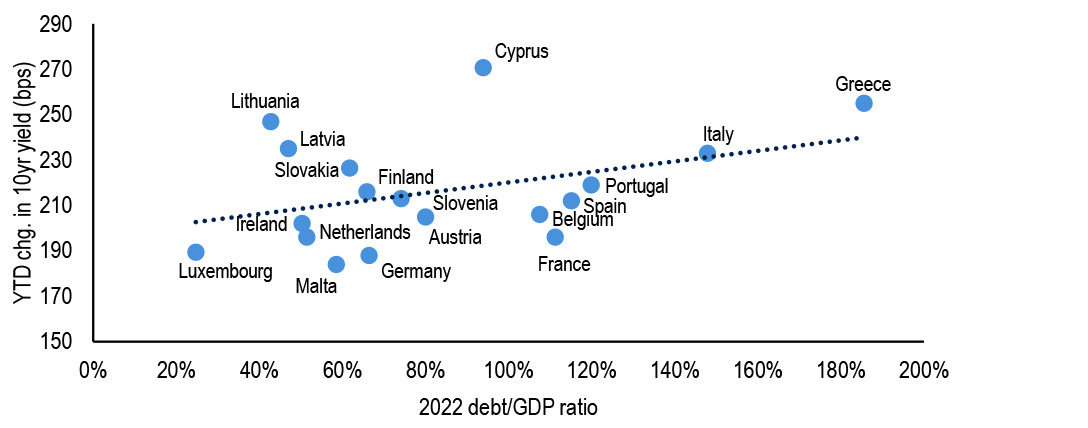

However, the ECB will need to walk a fine line between rate rises and preventing fragmentation risk, such as diverging financial conditions across countries. Issues are already evident with bond spreads widening in Southern European countries and the ECB’s composite indicator of systemic stress rising to its highest level since 2012, as markets have focused on the debt sustainability of highly indebted countries, such as Italy and Greece, in the face of rising rates. In reaction, an emergency ECB meeting led to the activation of the flexible reinvestment policy of the pandemic emergency purchase programme (PEPP), as well as the accelerated design of a new ‘anti-fragmentation tool’, to be launched in July alongside the first rise in rates. Early reports had suggested that the ECB could sell existing assets to buy Italian bonds.

But, arguably, this would require sales of German bunds given they represent the ECB’s largest holdings, a potentially politically unpalatable option. We would argue that a Securities Market Programme (SMP) or Outright Monetary Transaction (OMT) style purchase programme would be more appropriate, as it would not contradict the ECB’s normalisation policy as standard QE purchases would. The key distinction is that it would not expand the ECB balance sheet given purchases are ‘sterilised’, i.e. open market operations would drain the additional liquidity. Hence, it can be considered monetary policy neutral. Clearly, the ECB will hoping that the mere threat of such actions will be sufficient to rein in spreads and that the tool will not have to be used, as in 2012.

Chart 5: Markets are once again focusing on the more indebted EU19 countries

Estonia not included- does not have a 10yr bond

Sources: European Commission, Macrobond, Refinitiv

Of course, comparisons with 2012 will remain. But there are differences; interest expenditure is still lower, and longer debt maturities mean it will take longer for higher rates to feed through. Banks are in a better position too. Expansionary fiscal policy in the form of NextGenEU should also not be ignored. There are some signs of this. For example, in Italy, the investment contribution to quarterly GDP growth has averaged 0.6 percentage points in the last three quarters, versus 0.1% over the last 20 years. Nonetheless, growth headwinds cannot be ignored and we have cut our growth forecasts to 2.9% of GDP in 2022 and 1.4% in 2023. Whilst we believe a recession will be avoided, the risks are clear, especially around possible energy shortages this winter. The gravity of the situation was highlighted by Germany’s declaration of phase two of its emergency gas plan.

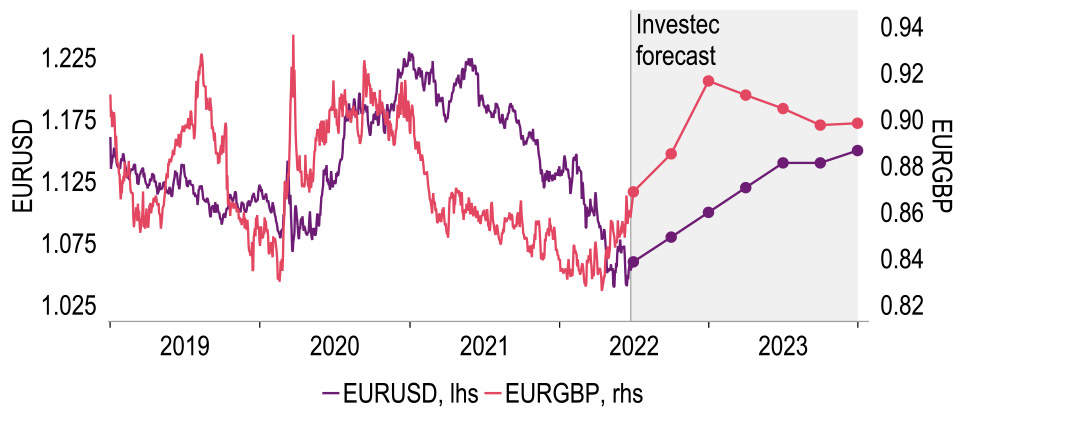

Given this outlook, we see the ECB pausing its normalisation over 2023. Downside risks, especially those related to energy, are a threat to the euro’s value, but provided those do not crystallise we see a rosier outlook in general, helped by the ECB’s hawkish pivot. An added driver once negative rates are exited in September is that sovereign funds may be drawn to rebalancing their holdings in favour of holding more euros. Hence, we see the euro gaining through the second half of this year, to 1.10 against the US dollar and 92p against sterling, compared with our previous estimate of 84p. Given our expectation of Fed easing next year but the ECB holding firm, the euro would then likely appreciate further through 2023 – our forecast for end-2023 is unchanged at $1.15.

Chart 6: The euro looks set to strengthen in the coming twelve months

Sources: Macrobond, Investec

United Kingdom

The UK economy is subject to the same recession risks weighing on markets. Although economic data for now remains relatively robust, there are warning signs of an impending economic slowdown. Indeed, the economy has not expanded for the last three monthly GDP reports. Considering the cost-of-living crisis and the successive tightening in monetary policy, we expect the UK economy to enter a short, mild recession starting in Q4 2022, which will force the Bank of England (BoE) to halt hiking and eventually cut rates by mid-2023 to support the economy. We have downgraded our GDP forecasts accordingly, to 3.3% in 2022 (previously 3.6%) and 0.5% in 2023 (previously 1.7%).

We expect the UK economy to enter a short, mild recession starting in Q4 2022, which will force the Bank of England (BoE) to halt hiking and eventually cut rates by mid-2023.

Alongside a more dovish approach to monetary policy, the tight labour market should help limit the depth of the expected downturn. Chancellor Rishi Sunak’s latest fiscal package will also lend support, with the BoE estimating that it will add 0.3 percentage point to GDP over the coming year. We do not believe, however, that these supporting factors will be enough to avoid a recession in its entirety. For example, although the current level of vacancies would support a rise in redundancies, history shows that job openings can quickly drop off in times of economic stress. Indeed, as economic momentum weakens, we are already noticing some easing in labour market conditions, such as slower employment growth.

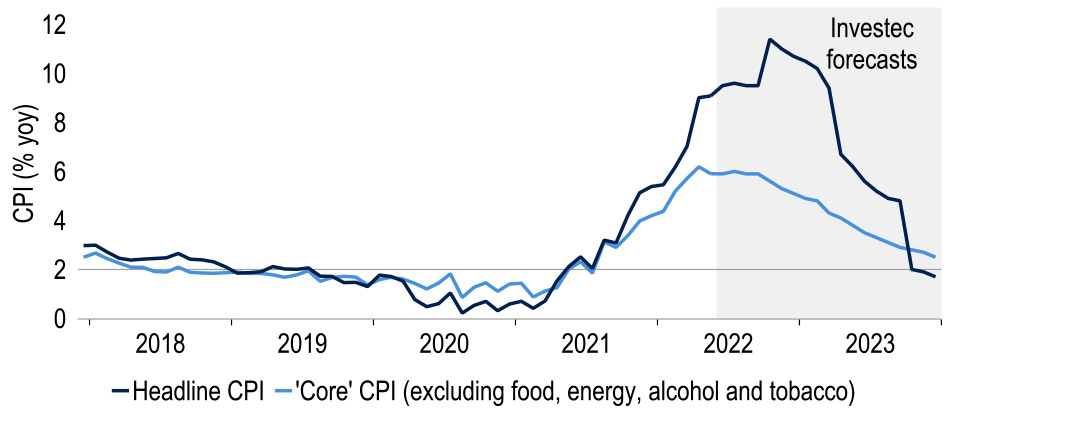

Furthermore, although the chancellor’s package will bump up economic growth, it will also be inflationary. We see headline CPI inflation exceeding 11% in Q4, weighing on the economy as real incomes are squeezed. Core CPI, however, is expected to ease in the coming months, but there are clear risks to this view. One is a possible wage-price spiral. Also, the potential for further weakness in sterling would keep underlying inflation higher for longer. Even if the core measure does ease back from here, steep increases in the cost of essentials, such as food and energy, are set to persist for a while longer. Afterwards, we still expect a sharp decline in the headline measure, not least as utility prices fall sharply from next spring.

Chart 7: UK headline CPI inflation to reach double digits, then fall back sharply

Sources: Macrobond, Investec forecasts

In such an environment, the path for monetary policy is not an easy one for the MPC to navigate. Thus far, the MPC has demonstrated its commitment to fighting inflation with five successive interest rate hikes. We expect that, despite the risks to growth, this hiking cycle still has room to run, pencilling in a further three 25 basis point hikes this year, resulting in a 2% peak in the bank rate. From here, we expect the economy to shudder to a stop under the weight of higher interest rates and enter a short recession, forcing the MPC to stop policy tightening. With headline CPI inflation still in double digits at the end of 2022 as per our forecasts, cutting rates at this point is likely to be a non-starter.

As such, we expect a policy pause followed by three successive 25 basis point cuts to the bank rate from mid-2023, when inflation is less of a medium-term danger. We envisage an end-2023 bank rate of 1.25%. This call naturally impacts our thinking on sterling strength. So far this year, cable or pound-dollar has been under considerable pressure as the dollar was boosted by an aggressive pace of monetary tightening by the Fed. However, this is not the only story. Sterling has also been vulnerable due to domestic factors, such as tensions over the Northern Ireland protocol and the risk of a recession. We expect this to weigh further on the pound in the coming months and as such have adjusted our end-year cable forecast to $1.20 (92p) and end-2023 to $1.28 (90p).

Johnson’s government battles on, with the cost-of-living crisis front and centre as the UK heads for recession.

Generally, political uncertainty adversely affects countries’ currencies. But given the hostile stance towards the EU and the waning public support for the Conservatives, investors may welcome a change. Indeed, the 23 June by-elections in Wakefield and Tiverton & Honiton highlight Tory woes, with both being lost despite being at opposite ends of the political spectrum. Boris Johnson may have survived a vote of no confidence among his own MPs, 211-148, yet further mire would undoubtedly place greater pressure on the prime minister – a 2022-exit is priced at 2/1. For now, Johnson’s government battles on, with the cost-of-living crisis front and centre as the UK heads for recession.

Chart 8: Conservatives lose by-elections in both Wakefield and Tiverton & Honiton

Sources: House of Commons Library, Macrobond, Investec

Get more FX market insights

Stay up to date with our FX insights hub, where our dedicated experts help provide the knowledge to navigate the currency markets.

Browse articles in

Please note: the content on this page is provided for information purposes only and should not be construed as an offer, or a solicitation of an offer, to buy or sell financial instruments. This content does not constitute a personal recommendation and is not investment advice.