After months of gridlock over Brexit, the UK is holding an election that could have enormous implications for its economy and its relations with the world. In a highly divisive political climate, and with voter behaviour more unpredictable than in the past, we analyse the main potential scenarios.

Current opinion polls indicate a victory for the ruling Conservative Party at the election on 12 December is more likely than any other result. But there are a few factors that prevent the outcome from being a foregone conclusion.

Firstly, amid the polarising atmosphere caused by Brexit, there’s the potential for Britons to forgo their traditional political allegiances and switch parties depending on their stance toward the European Union. Also, several parties are promoting tactical voting. And after 2017’s election upset, when the then-Conservative Prime Minister Theresa May lost a substantial lead in the polls and her majority, nothing should be ruled out.

The electoral landscape has also changed in the past two years and made life harder for the UK’s two main political parties. Competition from smaller parties with a stronger stance on Brexit has pulled the Conservatives into a more anti-EU position and Labour into a more pro-EU one. With the threat of support leaking to these challengers, the critical issue at this election will be who can better unify one of the two Brexit tribes – leave and remain – either within the same party or across an alliance.

Likewise, polls indicate this election is shaping up to be a proxy second EU referendum. Voters effectively have a choice of either backing Prime Minister Boris Johnson’s vision of Brexit or supporting an alliance of political parties, centred on Labour, which has proposed giving the public a second say on staying in the EU.

But the parties are not just divided over Brexit. They are also standing on widely diverging spending plans and domestic policies. Any voter who allows their feelings toward the EU to dictate their choice at the ballot box could wake up the next day facing potential other policies they hadn’t fully anticipated.

With so much at stake, here are the main scenarios and what they could mean for individuals, businesses, and the economy.

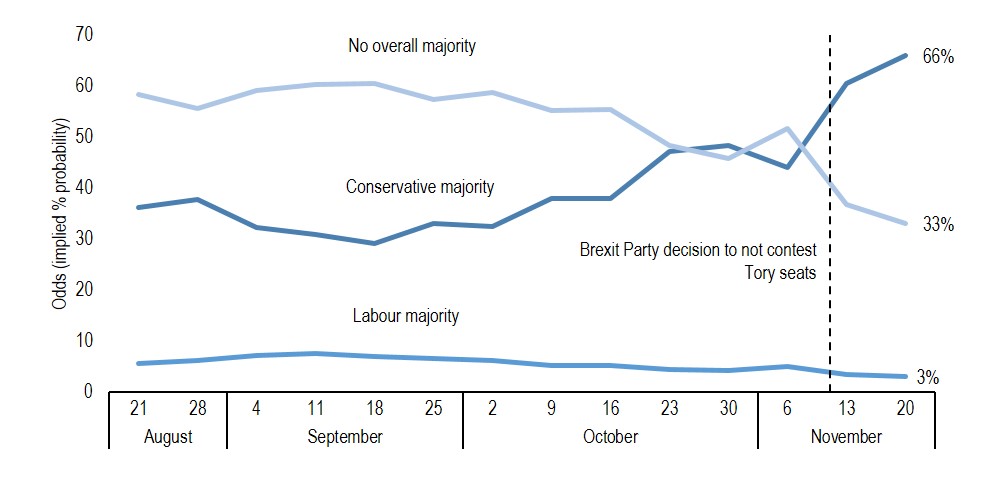

Betfair odds suggest a two-thirds probability for a Tory majority

Source: BetData (21/11/19)

What happens if the Conservatives win?

If the vote follows the polls and Johnson’s Conservatives win an outright majority, the UK could be on track to leave the EU with a deal on 31 January, followed by a transition period until at least the end of the year and an option to extend it to 2022.

The Conservatives are campaigning for the withdrawal deal agreed between Johnson and the EU, which puts Northern Ireland in a hybrid customs system, and a future Canada-style free trade agreement. That future arrangement points to a harder Brexit than that proposed by Theresa May, meaning a more significant impact on the economy, but much will depend on the final details. Still, the public spending increases that Johnson has proposed should partly offset this.

And while uncertainty about the when and how of Brexit will likely decrease in this scenario, businesses might quickly turn their attention to the detail of a future UK-EU free trade agreement. Questions remain about how close trade ties will be, and whether Johnson will be able to agree a deal by the end of the transition phase. He has vowed not to extend the transition period beyond 2020, raising the risk of a cliff-edge exit if the two sides have not reached a trade agreement. If no deal was achieved then the UK’s trade relationship with the EU would be on World Trade Organisation terms.

What happens if there's a hung parliament?

Polls indicate Labour is unlikely to win outright. But in the event of a hung parliament – where no one party has a majority – Labour may be in a better position to form a minority or coalition government with the support of the Scottish National Party and the Liberal Democrats. Given that all three are in favour of the British public having a second say on Brexit, this has been dubbed a “remain alliance.”

If such an administration takes office, the UK’s Brexit path will likely look quite different to that under the Conservatives, as will its domestic policy agenda.

First, Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn has said he would seek to extend the Brexit deadline beyond 31 January and renegotiate Johnson’s deal. Secondly, Corbyn has committed to negotiating a softer Brexit with a customs union and putting it to a referendum against the option of remaining in the EU.

Closer economic ties with the EU or the chance to cancel Brexit is likely to be welcomed by businesses. But they would have to weigh that up against the other significant consequences that a Labour-led government could bring: structural reforms that seek to overhaul the role of business in society, higher taxes, and the risk of a Scottish independence referendum that the SNP will demand.

Labour wants to increase the power of trade unions, introduce collective bargaining, nationalise key industries, and make companies with more than 250 employees give 10% of their shares to workers in “inclusive ownership funds.”

The Liberal Democrats will likely try and curb some of the most radical reforms, such as market interventions and nationalisations, so Labour may find its ambitions curtailed. Still, if investors and businesses become worried, private investment – especially foreign direct investment – could suffer.

While this scenario could dispel the clouds hanging over the economy from Brexit, it may be quickly replaced by the fog of uncertainty over the direction of domestic policy.

Other scenarios

Alternative outcomes to either an outright Conservative victory or Labour-led alliance are possible.

Firstly, the Conservatives could find themselves falling just short and having to team up with the Democratic Unionist Party and the Brexit Party for a majority (every other party has ruled out working with the Conservatives). In this scenario, Johnson may find his Brexit deal in jeopardy – especially as the DUP oppose what it means for Northern Ireland – and any internal opposition could limit his room for manoeuvre. A continuation of the current Brexit uncertainty and parliamentary gridlock could ensue.

There may be no majority for either a deal with the EU or a repeat referendum, leaving the parliamentary stalemate in place.

However, in the event of no one party or grouping of parties commanding a stable majority, the threat of further deadlock and the UK’s impending departure from the EU on 31 January could prompt the creation of a cross-parliamentary bloc of MPs under a caretaker government. The aim would likely be to break the logjam by either passing a Brexit deal or a second EU referendum.

Still, hope that the election resolves the Brexit impasse might turn but to be entirely misplaced. There may be no majority for either a deal with the EU or a repeat referendum, leaving the parliamentary stalemate in place. With the clock ticking, this would put the risk of a no-deal Brexit and further extension requests back on the table. In this scenario, Britain would likely be heading for another election in 2020.

The beginning of the end, or the end of the beginning?

The upcoming UK election could decide the fate of Brexit. It also appears likely that, given that all the main parties propose increased debt-funded public spending, it will lead to looser fiscal policy.

If voters decisively back either the Conservatives or a “remain alliance,” the removal of Brexit uncertainty holding back the economy combined with this fiscal stimulus could spur growth in the near term. Still, Labour's and the Liberal Democrat's plans for higher taxes could cap the economic boost from extra spending if they are in power.

What is also likely is that while a decisive election result one way or the other could help reduce doubts about Brexit, new uncertainties will probably replace them.

If Johnson secures support for his Brexit plan, the risk of a cliff-edge exit could return as he has ruled out seeking an extension of the transition period and obtaining a trade deal in time looks tight. Meanwhile, a Labour-led government could bring uncertainty with a second EU referendum in the short term and doubt over business reform in the longer term.

The election could also put Scottish independence back on the political agenda – either fueled by Johnson’s Brexit deal that takes Scotland out of the EU against its will while treating Northern Ireland differently, or by a push for a new referendum if Labour rely on SNP support.

We can’t be sure of the outcome, but two things look certain. This election is unlikely to remove all the clouds hanging over the economy. It is also unlikely to settle the country’s political divisions for long. Uncertainty in the UK appears to be the only new certainty.

Browse articles in