The Minister of Finance submits a Special Adjustment Budget to Parliament on Wednesday, 24 June 2020. This will be preceded by the Sustainable Infrastructure Development Symposium on Tuesday, 23 June. The supplementary budget is likely to make reference to Phase 3 which focuses on the return of public finances to a path of fiscal sustainability and positions the economy for structurally higher growth. But the key focus is likely to be a reset of the fiscal framework, necessitated by government’s Phase 1 and Phase 2 response to the Covid-19 pandemic, but also to address the sharply raised trajectory of government’s debt to GDP ratio (which could exceed nominal GDP by 2024 as signaled by the Minister of Finance last week). National Treasury’s growth strategy entitled Economic transformation, inclusive growth, and competitiveness: Towards an economic strategy for South Africa, which was endorsed by Cabinet, and the announcement of a pipeline of projects at the Infrastructure Symposium, are not expected to be factored into the baseline GDP growth forecast but rather as an upside risk scenario. The economic risk rating is likely to remain weak, with the route to a stronger GDP outlook -required to lower the risk premium on government bonds - likely to remain unclear.

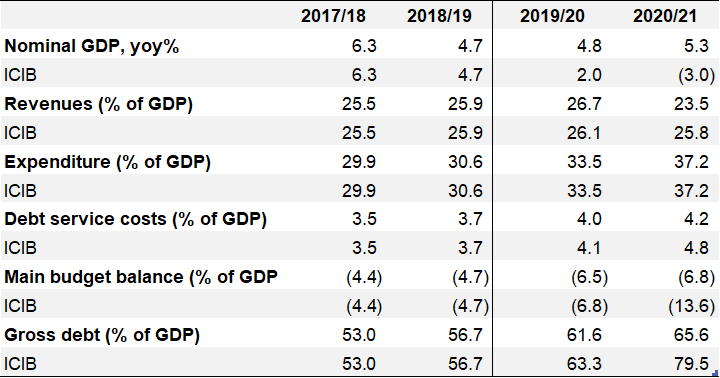

Table 1: Main budget forecast: National Treasury February 2020 and ICIB

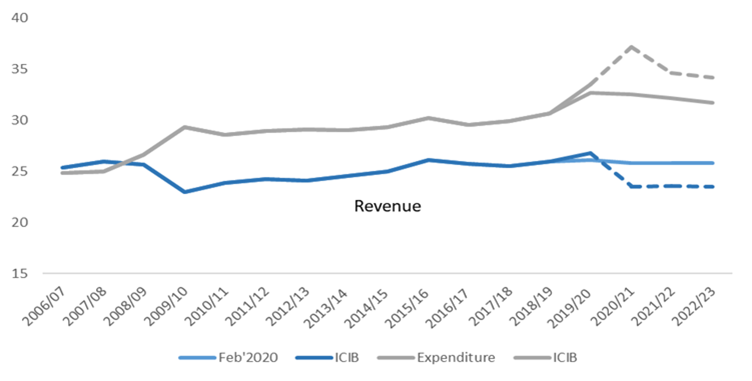

Figure 1 Main revenue and expenditure (% of GDP)

Macro economic forecasts: The macro economic forecast assumptions that underlie our forecasts remain highly fluid. The range of Bloomberg real GDP forecasts is between -4% to -11%, with the median at -7.4%. This is similar to the Reserve Bank’s forecast of -7.1%. In April, National Treasury provided a scenario analysis of GDP growth with Quick, Slow and Long lockdowns with 2020 GDP decline in the growth rate projected at -5.4%, -12.1% and -16.1% respectively. National Treasury’s forecast could be somewhere between the Quick and Slow scenarios at around -8%. ICIB forecasts a decline in nominal GDP of nearly 3.0% compared to the February 2020 budget assumption of +5.3%.

Main revenue receipts: In early May, the Commissioner of SARS indicated that tax receipts in F20/21 could miss the target by between 15% to 20%. This translates into a R214bn to R285bn shortfall. We assume this factors in R26bn of revenue foregone due to the expansion of employment tax incentives, payment of the skills development levy holiday for four months and deferral of 35% of PAYE liabilities and provisional tax payments. ICIB’s baseline gross tax revenues assume a shortfall of R259bn. Non-tax revenues account for 3-5% of main revenue receipts (or R36bn). This could be enhanced by the auction of spectrum that is likely to generate approximately R12bn. SACU payments to the BLNS countries could be revised down from R63.4bn, with monthly receipts during the lockdown having fallen short by R6-7bn of the estimated monthly receipts of R10bn. Our baseline forecast assumes main revenue receipts (which is comprised of gross tax receipts, non-tax revenues and net of SACU payments) in F20/21 to decline by 13.3% y-o-y (or R235.0bn) compared to the forecast in February 2020 of an increase of 4.0% y-o-y. We do not anticipate announcement of tax increases to close the budget gap, as the size of the budget deficit is of a such a magnitude that an increase in VAT or PIT will make very little difference to the borrowing requirement. Tax buoyancy assumptions are difficult to make with a decline in the tax base a major concern. Main tax revenues could decline to 23.5% of GDP compared to the initial forecast of 25.8%. Hence the expenditure side of the budget will be the critical lever to contain South Africa’s debt trajectory. The tax gap is estimated to be approximately R50bn, but this is a longer term problem.

Main expenditure: The outlook for expenditure remains highly uncertain due to political agendas and lack of policy clarity. Areas of specific concern/risk include SOE’s in need of further liquidity support/government guarantees and public sector wage increases. The Minister of Finance and President Ramaphosa have both referred to zero-based budgeting which means the starting point for a departmental budget is zero and every rand spent needs to be justified. It is unclear how this type of policy will be implemented in a Medium Term Economic Framework (MTEF), as well as in the context of the public sector wage bill which is a fixed cost. This could also refer to the reprioritisation of national departmental budgets to the fiscal support programme (requiring a reduction in many departmental budgets) in F20/21. Spending reductions on non-essential items and savings lower the base from F21/22, potentially containing the fiscal support spending of R190bn to a once off in the current fiscal year. An important development could be the stickiness of such reductions as this implies a structural decline of potentially R130bn in spending. We have penciled in an increase of R75.0bn in main expenditure, which leads to an increase of 9.4% y-o-y compared to the February target of 5.0% y-o-y. Expenditure could rise to 37.2% of GDP compared to the February forecast of 32.5%.

- Change in spending priorities: The fiscal support package of R500bn announced by President Ramaphosa on the 21st of April consists of R190bn of spending which will be allocated under the main budget. This consists of support to municipalities (R20bn), health and frontline services (R20bn), additional social grants (R50bn); job creation and protection (R100bn). The reprioritization of spending from the baseline departmental programmes and budgets will account for R130bn , leaving a balance of R70bn to be funded through an increase in borrowing.

- SOE support could be rolled over to October MTBPS: The extent to which more financial support or guarantees will be provided to the ever increasing number of SOE’s requiring liquidity assistance poses upside risk to expenditure. This upside risk includes an amount of R67.1bn of direct financial support to SOE’s such as Eskom (R56bn), SAA (R10.3bn) and Denel (R0.6bn). Government guarantees in March 2020 amounted to R484.4bn of which R385.3bn or 7.6% of GDP have been utilised. We think it is likely that decisions for most of the SOE’s, with the exception of perhaps SAA, will be rolled over to the October MTBPS, following the appointment of a presidential SOE council on 11 June 2020. Possible increases in guarantees are likely to be extended to the Land Bank and Denel.

- Public sector wage bill: This is yet another unresolved issue. Public sector trade unions are taking the South African government to the Labour court to implement the final year of the three year wage deal. The implementation of a zero percent salary increase in F20/21 has however shaved off R37bn from the F20/21 public compensation bill forecast and lowered the base over the MTEF period.

- Debt servicing costs: Interest payments will continue to accelerate and absorb a larger share of revenues, rising to an estimated 4.1% of GDP in F20/21 from 2.2% in F09/10. This signals the risk of a debt trap if (1) expenditure is not reduced; (2) nominal GDP does not accelerate, and (3) bond yields do not decline. The growth rate in the annual rate of increase could accelerate from 12.8% y-o-y last year to more than 16.0% y-o-y in F20/21. In addition to the increased amount of funding to be raised due to the widening of the budget deficit, government debt and debt servicing costs will be impacted by the depreciation of the ZAR by 20.6% from the February Budget assumption of R14.5/$) and the level of interest rates (note that Treasury bill rates have declined but bond yields for maturities from 2031 and longer have increased). CPI inflation is expected to be 1ppt lower from the initial forecast of 4.5%. National Treasury has mainly issued shorter-dated and mid-long dated bonds with an average maturity of 9.4 years (only one issuance each of the R2037 and R2048).

Budget deficit could remain above 10% over the MTEF period: The consolidated budget deficit has traditionally been less than the main budget deficit because social security funds such as the UIF and Compensation Fund had surpluses. In F20/21, the initial forecasts showed a convergence of the consolidated and main budget deficit at 6.8% of GDP. The fiscal support programme includes transfers and subsidies from the UIF of R60bn. The consolidated budget deficit is forecast to widen to 14.8% of GDP compared to the main budget deficit, which could reach 13.6% of GDP. We think that the main budget deficit is likely to remain above 10% over the MTEF period.

The size of the main borrowing requirement could increase to R705bn (13.6% of GDP) from February’s forecast of R368bn (8.0% of GDP). The key financing focus points will be on IMF assistance, a drawdown on cash deposits and government bond issuance. The size of the current weekly nominal and inflation linked bond auctions is aimed to raise R337.7bn as set out in the February 2020 forecast. The issues that could impact the size of the borrowing requirement would be (1) switch auctions of the R208; (2) non-competitive bond auctions (which has raised a nominal amount of R35.1bn) and a drawdown in cash balances. A decision to utilize the sterilization deposit of R67bn holds implications for the money market shortage. However, the risk to bond issuance is to the upside at around R1.3bn per week but we do not expect an increase to be announced as early as this week.

Debt trajectory: The debt trajectory is expected to deteriorate significantly due to the combined effects of lower nominal GDP growth, the increase in the main budget deficit, the weaker rand and to the extent of longer-dated bond issuance. We forecast an increase in F20/21 from 65.6% of GDP to 79.5% and 90.6% through F22/23. We think that National Treasury could publish a longer trajectory which could show a breach of the 100% of GDP level by 2024 and climbing to 113% by F28/29 (according to social media reports) .