Water, the key to life

02 November 2021

Civilisation as we know it is built on a reliable supply of fresh, clean water. It’s essential that we ensure access to this precious resource.

3 min read

02 Nov 2021

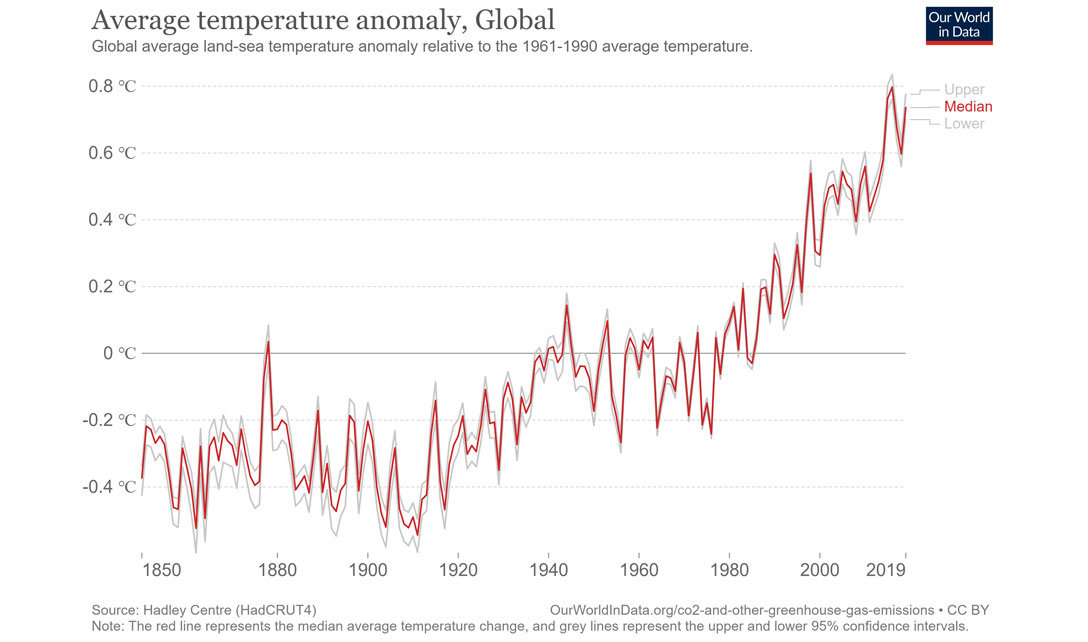

Firstly, why does climate change matter? Human emissions of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases (such as methane) are the primary driver of climate change. Climate change is one of our most pressing challenges. Since 1850, average global temperatures have risen 1.1˚C [1]. Whilst specific scenarios of temperature rise are beyond the scope of this article, every incremental degree of warming translates into increased chronic risks (water shortages and sea level rises) and acute ones (storms, floods and wildfires). The takeaway is that the sooner emissions are reduced and the lower we can limit temperature rises, the better the outlook for humanity.

The chart below shows average global temperature changes since 1850 and their clear upward trend:

COP26 is the 26th event in a series of annual conferences, which have been running since 1995. The goal of the events is to check in on progress made by members of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (‘UNFCCC’) to limit climate change.

Often there is not much of significance that happens at these conferences but in 2015, delegates came up with something quite special. This was the Paris Agreement, named because of the location of COP that year.

The Paris Agreement is a legally binding international treaty on climate change. It came into force in November 2016. In plain language, the agreement:

The methodology for reducing emissions under Paris is reached by nationally determined contributions (‘NDCs’), with each country deciding what is obtainable domestically and committing to achieving that. Progress must be reported on regularly, and every five years all countries submit new NDCs. Countries’ new NDCs have a clear expectation of being progressively bolder. This process can be thought of as a ratchetting mechanism, with commitments growing with time.

So far, net zero pledges to date cover around 70% of global GDP and CO2 emissions

Almost every country in the world has ratified the Paris Agreement [2], enshrining it in their own laws. This is a remarkable achievement and the number of countries pledging to reduce emissions and reach net zero has been increasing. So far, net zero pledges to date cover around 70% of global GDP and CO2 emissions [3] but most of these pledges have not yet found their ways into national legislation and are at risk of political regime change.

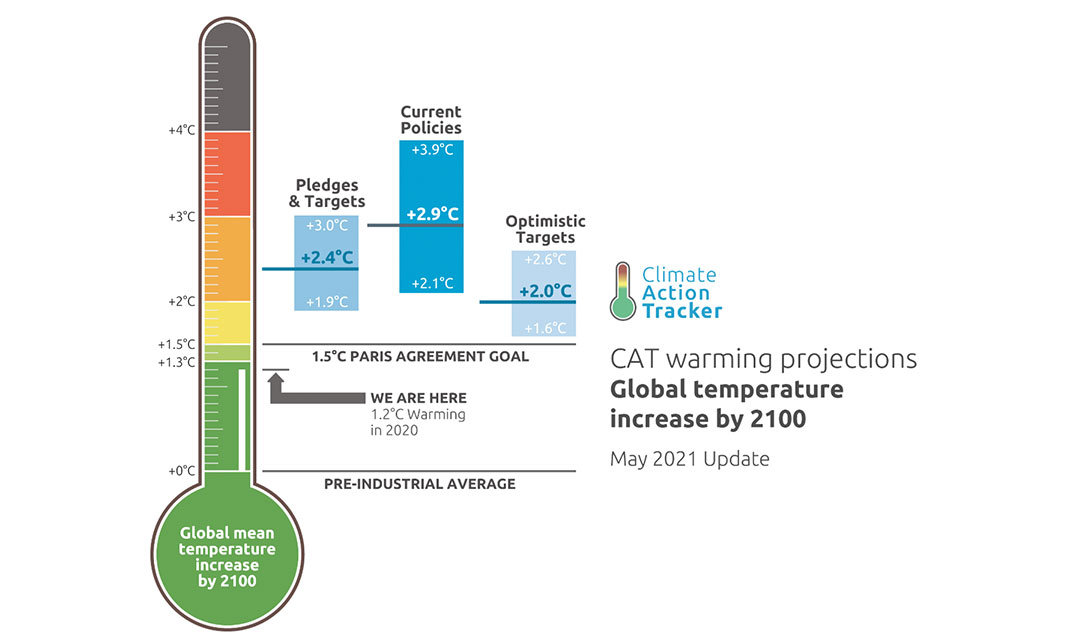

To have any chance of achieving no more than a 1.5˚C scenario, global emissions must halve by 2030 and reach ‘net zero’ by 2050. The Climate Action Tracker shows the likely course for temperature increases by the end of the century, looking at different scenarios of action. If all pledges and targets are reached globally a scenario of c.2.4˚C is currently on the cards. To achieve the goals of Paris, more action is needed.

Source: The CAT Thermometer | Climate Action Tracker

New NDCs, ambitious enough to put the world on track for ‘well below’ 2 degrees would be a start. Agreeing on what rules should govern international carbon markets – the Article 6 negotiations – would be better still. This has proved a tough area of negotiation and relates to carbon taxes and border adjustments.

In terms of background, one of the greatest failures of our economic system is described as the ‘tragedy of the commons’. The idea is that individual users who have open access to an unpriced resource, acting in their own self-interest, will overuse that resource to the point of depletion. Commons in this context therefore applies to open access to unregulated resources such as the atmosphere. Given that companies do not have to pay toward the damaging emissions they release into the environment, we have ended up in the situation we are in today.

One solution might be to start pricing these emissions using a carbon tax. A carbon tax is a fee on the consumption of carbon intensive products. By increasing the cost of emissions, carbon taxes make greener choices more competitive.

A global harmonised carbon tax would be ideal but is perhaps not realistic. Instead, local ones are likely to pop up. There is a risk of such local taxes working in practice because of something dubbed ‘carbon leakage’. Should the UK, for example, impose a carbon tax in isolation to the rest of the world, companies are likely to simply import products from overseas, where manufacturers were not subject to similar taxes. A carbon border adjustment mechanism is therefore needed to ensure ambitious local policies result in a reduction in global emissions rather than just pushing the production of certain goods overseas.

Products likely to be covered in initial proposals for such a border adjustment are cement, metals, fertiliser and electricity.

The EU and America are at the forefront of such an idea. Progress in this area could make marked differences toward a brighter and greener future.