The dollar price of coffee has almost doubled in the last year, a shortage of Brazilian rain and shipping containers raising the cost of caffeinated highs.

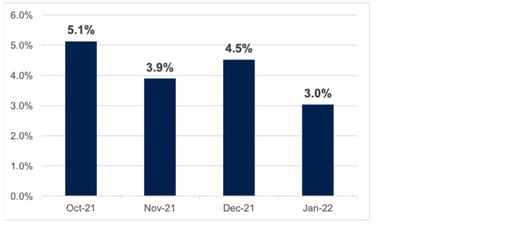

Look at nearly any global food stuff and you’ll see evidence of gummed-up supply-chains, higher raw material costs and more expensive labour reflected in fuller prices. Yet food inflation in South Africa (Figure 1) seems oblivious to those forces.

Figure 1: Average inflation across 40 key line items

Source: Investec Securities estimates

This is a welcome divergence: the poor, of which South Africa has many, spend a greater share of their income warding off hunger – food inflation hits them hardest. Smaller bars (above) lessen their daily struggle and thin the tinder for social unrest. Amongst other factors, this lower food inflation appears to come at a cost to suppliers, who are bearing the brunt of higher inputs cost and eroding gross profit margins.

Sensitive and self-sufficient

“I think the CPI number produced by Stats SA is a bit of a misnomer. It assumes the basket of goods bought by consumers remains constant when we know they change their buying behaviour based on price movements.”

That was David Smith, an equity research analyst at Investec. His insight partly explains the containment of SA food inflation; our producers and retailers know very well that their patrons are price sensitive. And because that dynamic has been in place for some time, they run lean and mean operations that are capable of absorbing or mitigating higher input costs, rather than passing them on to the consumer.

Mostly though, we can thank the diversity of our terroir, and its ability to support a wide range of crops, for our insulation against rampant global food inflation – we don’t need to import much. And with our vast unemployment, the wage pressure building across the world is unlikely to materialise on home soil.

Breaking points

When things are going right, it’s time to be vigilant. The following factors – in estimated, descending order of likelihood – could stir SA food inflation:

Russia invades

Ukraine is the 5th biggest exporter of wheat, a commodity that SA does import. War could remove that supply from the market and push prices higher still.

Retailers take no more

In the last financial reporting season, most retailers made it clear they were considering price increases to protect their margins from rising input costs. As lean as they are, the breaking point is near.

Fuel and fertiliser on fire

The big rise in fuel costs is arguably not yet reflecting in our food prices. If the oil price stays high or rises further, distribution costs will eventually stir those on the shelf. The same can be said for production costs, with the price of the chemicals (ammonia, nitrogen, urea) and energy (natural gas) used to manufacture crop fertiliser well through the roof.

The rand blows

Although somewhat agriculturally self-sufficient, a materially weaker currency would stoke food inflation. This is unlikely in an environment of strong commodity prices; political risk or a global risk-off event are better candidates.

Wet, wet, wet

The prevailing La Nina climate pattern has sowed some concern that our summer crops would suffer the wash of floodwaters. Those fears seem to be subsiding, but with saturated soil, a tail risk remains.

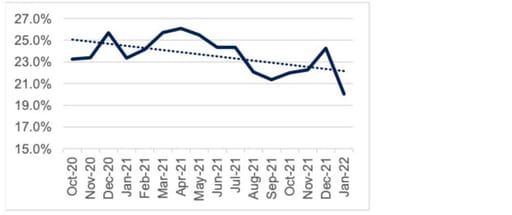

A private-label hedge

The argument could be made that the risk to SA food inflation is to the upside. And with weak economic growth and stubborn unemployment, producers and retailers alike will need to balance margin goals and an increasingly fickle consumer. For example, evidence (Figure 3) suggests that shoppers are already shifting away from brands in favour of private-label offerings.

Figure 3: Average premium of branded goods over private label

Source: Investec Securities estimates

An exploration of the above trend line, and what it means for private-label development, will be the subject of another piece. In the meantime, enjoy your relatively cheap morning coffee.