White labelling is a long-established strategy in the South African consumer market and continues to be widely used by manufacturers and retailers.

It’s a strategy that’s extended to other products over the years, including electronic goods, computers and even packaged services, such as mobile data or credit cards.

White labelling works for many manufacturers or suppliers because it provides a ready market for their products. Meanwhile for retailers, it’s an opportunity to place their brand name on high turnover product lines, as an alternative to branded products, and in that way build their own brands.

A growth opportunity for retailers?

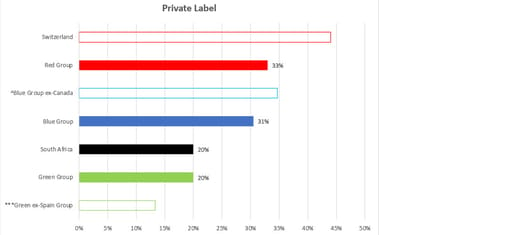

There appears to be significant scope for South African retailers to build scale through white labelled products. Data on the subject by Statista (in 2018) showed that private / white labelled goods made up an average 20% of the sales of South Africa’s top five retailers. This was shy of the 31% average in a peer group of countries (where the largest five retailers had a market share of between 70% and 80%).

Where retailers are looking to grow sales in white labelled goods, they will also want to ensure the products on their shelves that bear their name are associated with quality and value for money. For this reason, retailers will work closely with their white label partners to ensure ongoing quality control. Examples of such a deeply collaborative and mutually beneficial white labelling supply arrangement include Rhodes Food Group (RFG) and Libstar, both of which supply Woolworths.

As a result, many white labelling arrangements are long-standing in nature, reflecting a relationship that works for both parties. Many manufacturers will of course provide their own branded products to retailers. For instance, RFG supplies both white label and branded products to its food retail customers.

Figure 1: Top five retailers combined market shares

Source: Statista, Investec

Challenges for manufacturers

In an environment where producer prices are rising due to global bottlenecks, manufacturers may be finding their margins under pressure. To counter for the loss of margin, manufacturers may look to increased use of white labelling agreements to secure and grow their revenue lines.

This could also dovetail with retailers’ strategies in growing their white label lines, especially among cost-conscious consumers. Our own back-of-the-envelope analysis of a small group of products (milk, sugar, rice and dishwashing liquid) at four of SA’s leading FMCG retailers, showed that branded products are often priced at 20% or higher (and in a few instances, much higher) than their white label equivalents. We should note that these numbers can vary considerably from month to month and from retailer to retailer, but the broad implication is that there is considerable opportunity to grow the white label offering among value-driven consumers.

There are of course a number of factors and risks to consider when going down this road, such as securing shelf space in already competitive product lines, possible cannibalisation of the manufacturers’ own branded products and customer loyalty towards branded products in any particular line.

Fortunately, South Africa can however count on a number of high quality – and in many cases, world class – FMCG manufacturers and retailers. For this reason, considerable scope exists for maximising white labelling for retailers and manufacturers alike, while delivering a value-for-money offering for consumers, and a trend we will be keeping an eye on in the future.