Get Focus insights straight to your inbox

Around the world, governments and central banks are pouring money into the system to mitigate the impact of the lockdowns on their economies.

Already high levels of government spending have increased further, leading many economists to start to talk about a new age of inflation coming down the track in the next few years. Could this come to pass?

Even before the pandemic, economists and strategists had been suggesting that higher inflation could be seen in the coming years. Michael Hartnett, of Bank of America, suggested in September last year that inflation could be one of the themes of the coming decade

(Hartnett also suggested a number of other reversals from the previous decade, including shifts from inequality to redistribution, from globalisation to protectionism, from monetarism to Keynesianism, from lower taxes to higher taxes, from bank deleveraging to corporate deleveraging, and from quantitative easing (QE) to modern monetary theory (MMT). These shifts are linked, as we shall explain below).

Making the analogy between the fight against Covid-19 and a major war, some economists believe that the levels of spending and increased debt could have the same inflationary outcome as the spending on wars in previous generations.

Many others are now saying something similar. Making the analogy between the fight against Covid-19 and a major war, some economists believe that the levels of spending and increased debt could have the same inflationary outcome as the spending on wars in previous generations. Germany for example, tried to inflate away its First World War debt in the early 1920s, leading to the hyperinflation with which the Weimar Republic has become synonymous. The UK’s government debt levels of 250% of GDP after the Second World War were partly alleviated by mildly higher inflation.

According to Charles Goodhart and Manoj Pradhan of the London School of Economics, the initial impact of the pandemic and lockdown measures has been disinflationary. Any supply-side disruptions have been met by a collapse in demand. The oversupply in the oil market in late April (which briefly pushed crude oil prices into negative territory) may also keep the lid on prices for a while.

Moreover, inflation might not emerge in a hurry after the pandemic has ended. Household and government balance sheets will take time to repair, while the trauma of the lockdown period may weigh on consumer confidence for a while.

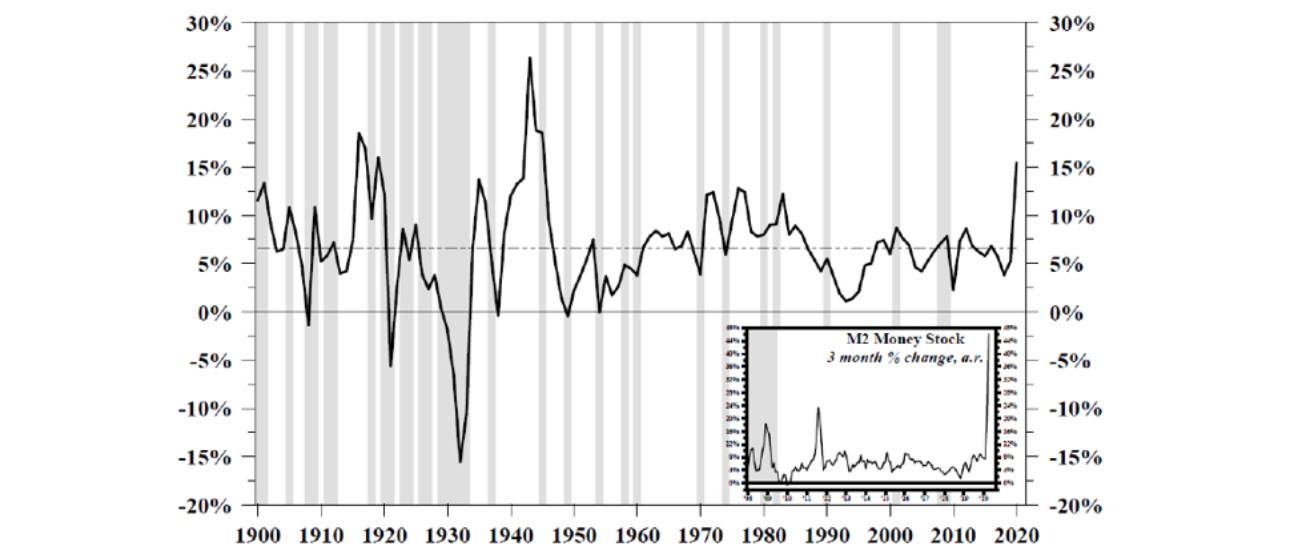

For how long though? And could higher inflation emerge thereafter? Traditional monetarists point to rises in the money base as a harbinger for future inflationary pressure. Writing in the Wall Street Journal in the early stages of the global lockdown, Tim Congdon of the Institute of International Monetary Research, noted how the Federal Reserve had pumped money into the system at its fastest rate in over 200 years. Using deposits at banks as a measure of the quantity of money, Congdon said the number could increase by as much as between 15% and 20% by this time next year.

“That wouldn’t quite match the peak rates of expansion seen during and immediately after the two world wars of the 20th century, but it could surpass peacetime records, outpacing the previous peaks in the inflationary 1970s,” he wrote.

US M2 money stock (annual percentage change) to 20 April 2020

Source: Federal Reserve, Hoisington Investment Management

Warnings of higher inflation are not new. The central bank interventions in the post-financial crisis years – notably QE – were widely expected at the time to become inflationary. Large levels of public debt and swelled central bank balance sheets created fears of a major inflationary jump later on.

Yet inflation has remained very low, particularly in the developed world. Part of the reason, as Goodhart and Pradhan explain, is that QE kept cash within the banking system in the form of excess reserves – rather than in broader money. Congdon notes that the quantity of money in the US from 2010 to 2018, matched nominal GDP growth, at an average of 4% a year. Furthermore, China played a key disinflationary role in the post-crisis years, through its competitively priced exports.

However a different story may play out in the coming years. One reason, according to the monetarists, is the rise in the quantity of money. Another is the likelihood of structural changes to the world economy. As noted above, some of these trends were already playing out before the coronavirus started to spread: populism, anti-globalisation and trade wars in particular could gain momentum in the coming years.

Part of the reason why inflation has been so well contained over the last three to four decades has been thanks to globalisation, particularly China’s growing role as an engine of global growth. The removal of tariffs and the creation of sophisticated global supply chains have made the provision of goods and services a ruthlessly competitive business. From foodstuffs to clothing to electronic goods and outsourced services, consumers and businesses have benefited from greater choice, quality and keen pricing.

Protectionism may intensify, in the form of higher tariffs to support local industries and jobs, while the backlash against immigration, already present in many developed economies in the last few years, could intensify.

However, faced with having to pick up the pieces after the pandemic, governments may find themselves tempted to follow populist policies. Protectionism may intensify, in the form of higher tariffs to support local industries and jobs, while the backlash against immigration, already present in many developed economies in the last few years, could intensify.

Keynesianism and its cousin, modern monetary theory, may come into vogue again. Governments may discard concerns about budget deficits to finance social spending or even introducing a universal basic income for their citizens.

Protecting local jobs and businesses is likely to have its own costs, including lower productivity, quality and efficiency. With diminished competition from abroad, local businesses will have less incentive to control costs or keep prices low. Workers, facing fewer threats from abroad or from migrants, will have greater wage bargaining power.

Governments may also be tempted to deal with the higher levels of debt incurred in the pandemic and in the spending programmes to satisfy their electorates, by allowing some inflation.

Central banks, with memories of QE still strong, may be loath to hike rates once inflationary pressures start to emerge, leading to inflationary overshoots further down the line. Those central banks that do try to raise rates may also face a backlash and threats to their independence.

Is inflation inevitable?

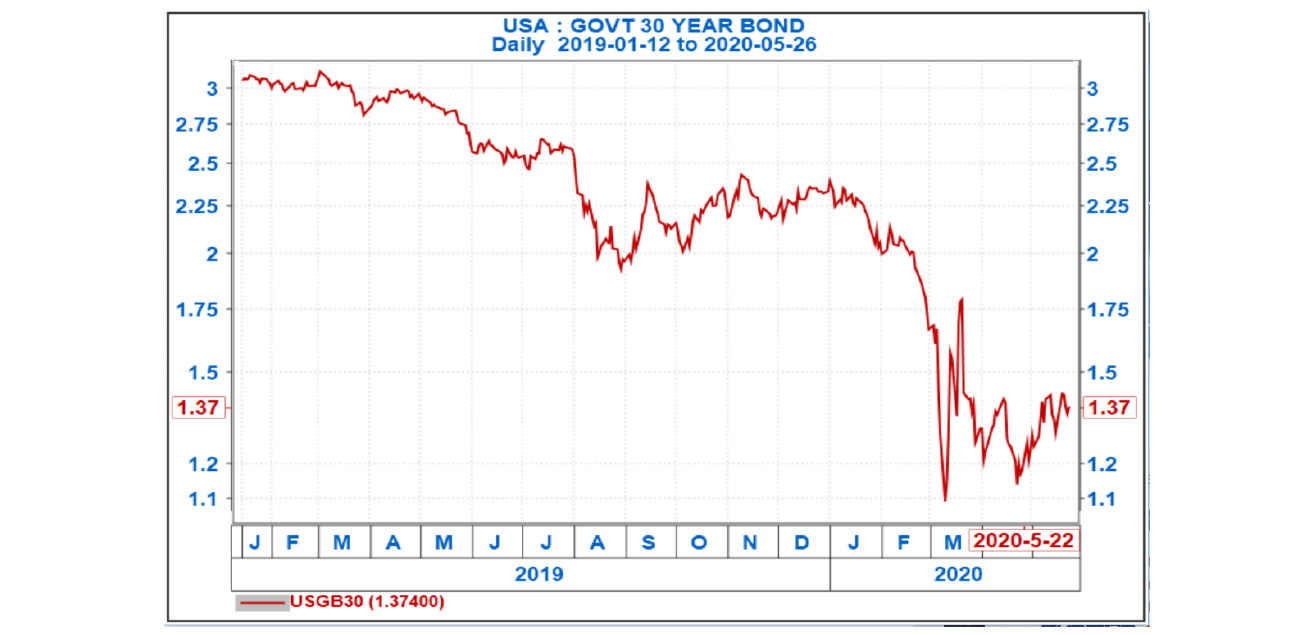

If markets were expecting inflation down the pike, we would probably be seeing it in higher long-dated bond yields. Thus far, developed market bond markets are telling a different story. US 30-year Treasuries currently trade around 1.5% and are down from around 3.5% in 2018. German 30-year Bunds trade at close to zero.

Figure 1: US 30-year Treasury yields

Source: Iress

At such rates, it would be reasonable to expect governments to use the current opportunity to fund their spending through longer-dated bonds, lessening the impact of higher indebtedness in years to come and the incentive to inflate their way out of trouble.

Furthermore, output gaps in the developed world may persist for a while longer as economies battle to emerge out of the damage caused by Covid-19. Demand-pull inflation seems a long way off, as bond markets appear to be telling us.

Equally, it’s not a given that central banks will be reticent to act decisively when faced with rising inflationary pressures.

Protectionism is a possibility, but so is the opposite. While the pandemic may have increased the temptation for governments to put up the shutters and look inwardly, its aftermath may also herald new efforts at cooperation between countries.

While goods may find their paths between countries blocked, the same is less true for services and intangible goods. Lockdowns may have confined people to their homes, but they have opened us up to the possibilities for working and interacting remotely, even between countries.

Technology too, can offset inflationary forces to some degree. Automation, artificial intelligence and robotics will help to keep costs down. At the same time, while goods may find their paths between countries blocked, the same is less true for services and intangible goods. Lockdowns may have confined people to their homes, but they have opened us up to the possibilities for working and interacting remotely, even between countries. Many skilled individuals may not need to emigrate from their home countries to realise their potential.

Advances in 3D printing could also transform manufacturing. With the basic materials and access to designs, a number of branded products can be “made” close to their markets, without having to be shipped from elsewhere or attract tariffs.

Which of these scenarios will play out? Clues will come from the broad money supply and bank credit trends, which central banks will be watching. We will then have to see how decisively they act to reverse policy and rein in any nascent inflation, if and when it appears.

In short, while we cannot rule out the dangers of rising inflation in the years to come, we should also not underestimate the counter-inflationary forces in the world.

About the author

Patrick Lawlor

Editor

Patrick writes and edits content for Investec Wealth & Investment, and Corporate and Institutional Banking, including editing the Daily View, Monthly View, and One Magazine - an online publication for Investec's Wealth clients. Patrick was a financial journalist for many years for publications such as Financial Mail, Finweek, and Business Report. He holds a BA and a PDM (Bus.Admin.) both from Wits University.