It is crunch time for most central banks – but not the South African Reserve Bank (SARB). Inflation rates escaped the grasp of many of the world’s leading central banks and recapturing it will not be a comfortable or simple exercise. Rising prices, rising wages and the prices of other inputs, can be blamed on the usual suspect – more money has been created than has been willingly held by households, business and banks. Excess money holdings (deposits at banks) have been exchanged for goods, services and other assets, enough to raise their scarcity value. And supply has been unusually slow to respond to the unexpected strength of demand.

It will take higher interest rates and a sharp deceleration of the rate of growth of the money supply to reverse inflation trends. It will demand that less be spent and borrowed by governments and more tax collected. Paying interest will account for an ever-larger share of government budgets to constrain the much more agreeable benefits that might otherwise be provided.

Their further problem is that higher prices are part of the adjustment economies make to address an excess of demand over supply. Higher prices have causes and effects – they help absorb and restrain demands while they encourage additional output. Higher prices reduce the ability of households to spend and the lower spending may register as temporarily slower growth, slow enough to make central bankers more hesitant to act. But, if they fail to act, they may encourage expectations of more inflation that will show up in higher long-term borrowing costs.

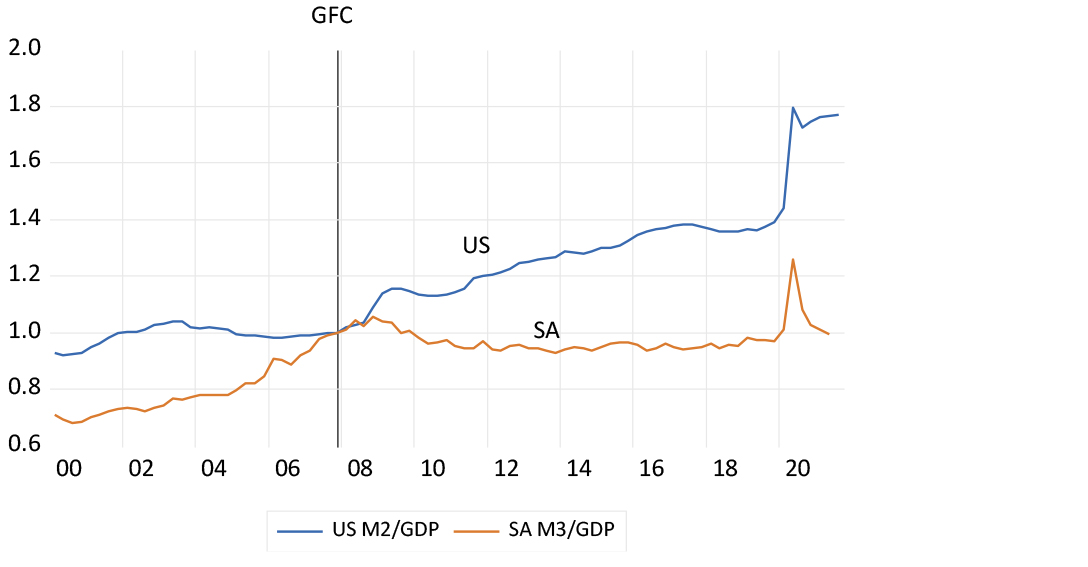

A further complication is that there is a great deal of money sitting on the sidelines waiting to enter the markets. The ratio of money relative to income (GDP) in the US has exploded since the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) in 2008 and in response to Covid-19 two years ago. There is now 80% more money, mostly in the form of bank deposits, per unit of income than there was in 2008. A ratio of close to one between income and money was very much the understandable case before the GFC and before the brave new world of quantitative easing (central bank money creation on a vast scale) was discovered. A new money/Income equilibrium will have to be established in the US. A mix of higher prices and less money added will have to bring this about.

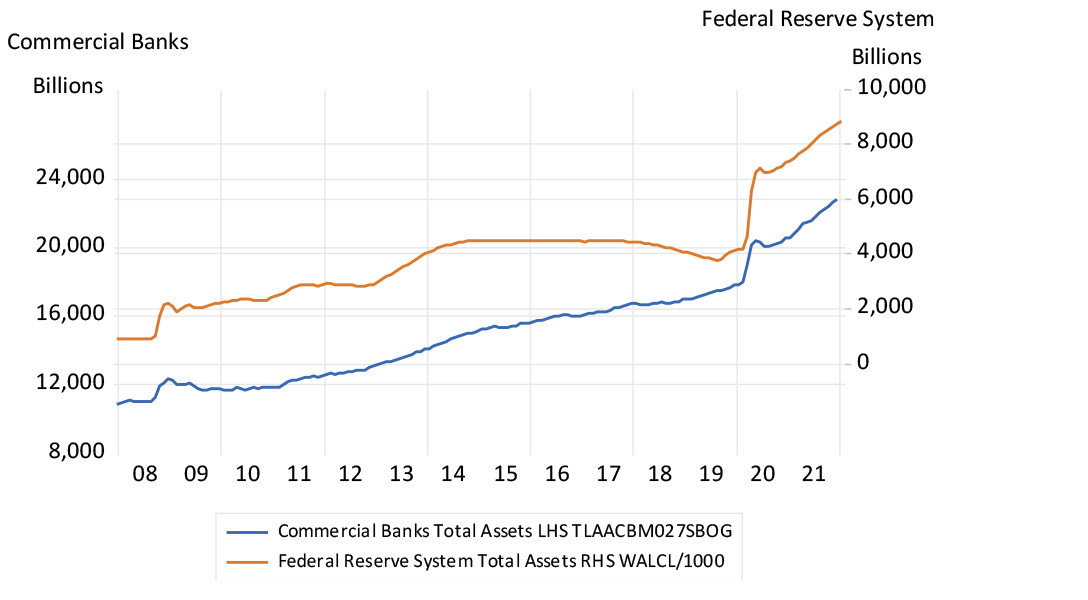

The commercial banks play a large role in determining the supply of deposits, through their lending. And they have vast reserves of cash to convert to loans if they choose to do so in response to demand for credit to expand the money supply further. The last time the Fed reversed quantitative easing in 2015, to shrink its own balance sheet, the balance sheets of the commercial banks continued to rise as they reduced their cash holdings in exchange for other assets. They may do so again. It might take much higher short-term interest rates to discourage them.

Assets of the US commercial banks and the Federal Reserve System 2008-2021 (in US$bn)

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St Louis (Fred) and Investec Wealth & Investment, 17/02/2022

We have a clear case of monetary excess in the US, in the form of an explosion of the money/income ratio. At the same time, we have too much monetary constraint in SA. This is enough to infer that the relationship between money and incomes has undergone a systemic change – in an inflationary direction for the US and a contractionary one for SA.

The US and SA – money to income ratios (2007 = 1)

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St Louis (Fred), South African Reserve Bank and Investec Wealth & Investment, 17/02/2022

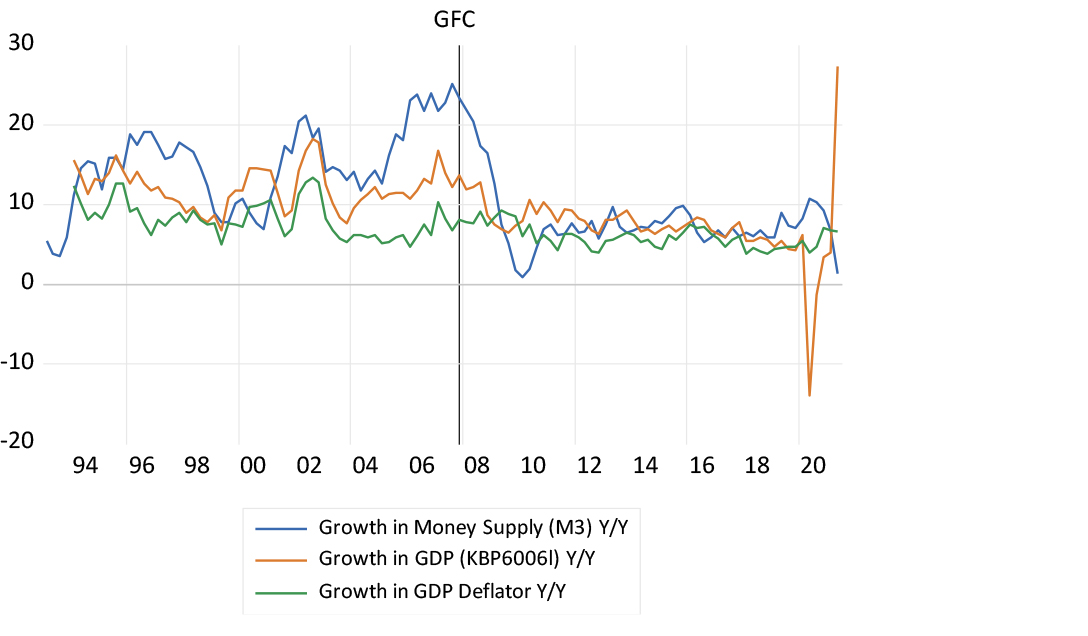

The sense of systemic change in South Africa is reinforced by a comparison of growth rates in money and income, before and after the GFC. Growth rates were much higher and more variable before 2008. They have declined significantly since. The Fed will have to tighten up to control inflation and the SARB should lighten up to facilitate faster growth. It’s essential that it supplies enough money – not too much nor too little – to achieve this.

Growth in South African money supply (M3), GDP and prices (quarterly data)

Source: South African Reserve Bank and Investec Wealth & Investment, 17/02/2022

About the author

Prof. Brian Kantor

Economist

Brian Kantor is a member of Investec's Global Investment Strategy Group. He was Head of Strategy at Investec Securities SA 2001-2008 and until recently, Head of Investment Strategy at Investec Wealth & Investment South Africa. Brian is Professor Emeritus of Economics at the University of Cape Town. He holds a B.Com and a B.A. (Hons), both from UCT.

Get Focus insights straight to your inbox