Global inflation has seemingly come as a surprise to all but the small tribe of monetarists who hold that any model of inflation should include a genuflection (a bending of the knee) to the role played by money.

More money, in the form of bank deposits, is likely to mean an excess of the supply of money over the willingness to hold onto that money and for other assets, goods and services to be substituted for money, thus adding to demand and to upward pressures on prices and output.

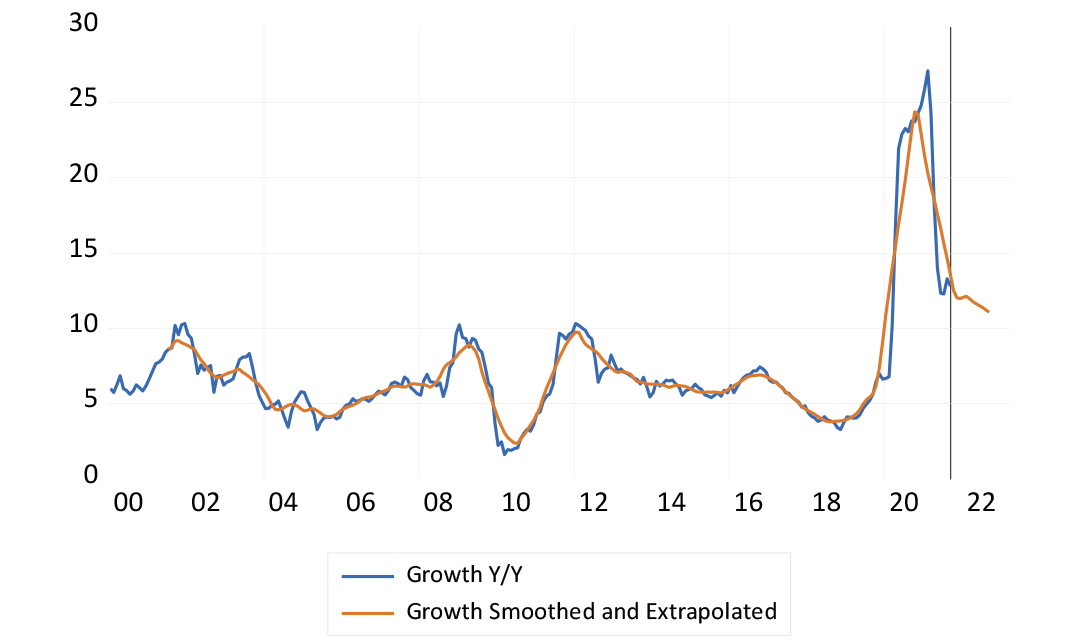

The value of deposits held in US banks and money market funds has grown by approximately 36%, or by US$5.5 trillion since January 2020. The system is heavily overweight with money and underweight with other assets, goods and services. Its impact on the demand for assets, goods, services and labour has been felt for some time. Covid stimulus has worked, if anything, too well.

Figure 1: Annual percentage growth in the US money supply (M2 – deposits and money market funds)

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St Louis, Investec Wealth & Investment, 18 November 2021

More wealth for home and share owners, including in the form of additional bank deposits, usually means less money saved and more consumed. And for those with extra deposits provided as Covid income relief, and who usually must live from pay cheque to pay cheque, are likely to continue to exchange their extra savings for goods and services, leading to additional pressure on prices. Banks, with vastly additional cash reserves at the central bank, are more likely to provide additional loans to fund additional spending. There is much more than lower or higher interest rates that explain the impact of money on output and prices.

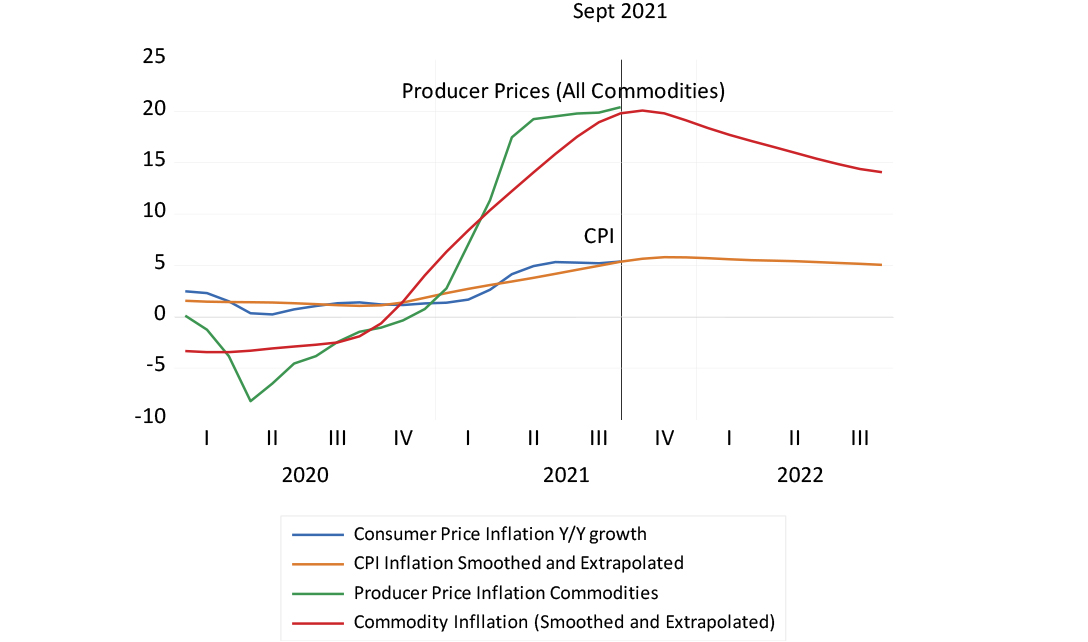

Prices paid by consumers in the US are 6% higher than they were a year ago and commodity prices for producers in September were 20% higher than they were a year ago. A mixture of too much demanded and too little supplied, has inevitably meant higher prices.

Consumer and producer inflation in the US

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St Louis, Investec Wealth & Investment, 18 November 2021

Will the current rate of price increases in the US extend beyond the next 12 to 24 months? The answer will depend on the pace of money supply growth in the years to come. It will have to slow down to something like the long-term average growth rates in money supply – about 6% a year between 2000 and 2020 – to return inflation rates to an average of 2%. This will require higher short-term interest rates and conservative fiscal policies to restrict demand. These are the adjustments to monetary and fiscal policy called for to restrain inflation over the longer run, but they will test the political independence of the Fed to raise interest rates and reverse its quantitative easing sooner rather than later.

The Federal Open Markets Committee, at its latest meeting, resolved to “taper” (reduce) its purchases of government and mortgage bonds in the market, at the rate of US$15bn a month. This will still mean a large amount of money added to the system, and to additional spending for another 12 months. Furthermore, increases in short-term interest rates and borrowing costs are not expected until the tapering operations are completed. The state of the US economy and its especially buoyant labour market – with job vacancies far exceeding potential applicants and strong upward pressure on wage rates and employment benefits – calls for more urgent responses. It calls for not only tapering, but the reversal of it. In other words, net bond sales rather than net purchases and a reduction in the size of the Fed’s balance sheet, including the bank deposits (liabilities) held with it.

The ambition of the Biden administration to spend more on both physical and (as it is described) human infrastructure seems uninhibited.

The strength of the economy and the pressure on prices – and on the supply side of the economy – will test the willingness and ability of Congress to vote for higher taxes or reduce spending if inflation is to be contained. The ambition of the Biden administration to spend more on both physical and (as it is described) human infrastructure seems uninhibited. The connection between such plans and their inflationary consequences will never be made obvious, though in the final analysis the voters will decide how much extra government spending and taxes will go ahead. Inflation is not a popular condition in the US and that may well be the best reason to expect it to be contained in the end. Persistently high rates of inflation over the next two years however, seems unavoidable.

The SA economy, without the stimulus of QE and with minimal growth in its money supply since early 2020, suffers by contrast from too little demand. Yet we will also be subject to supply side shocks on the prices we will be paying. The Reserve Bank would be well advised not to add to the negative effects of higher supply side driven prices on demand with higher interest rates.

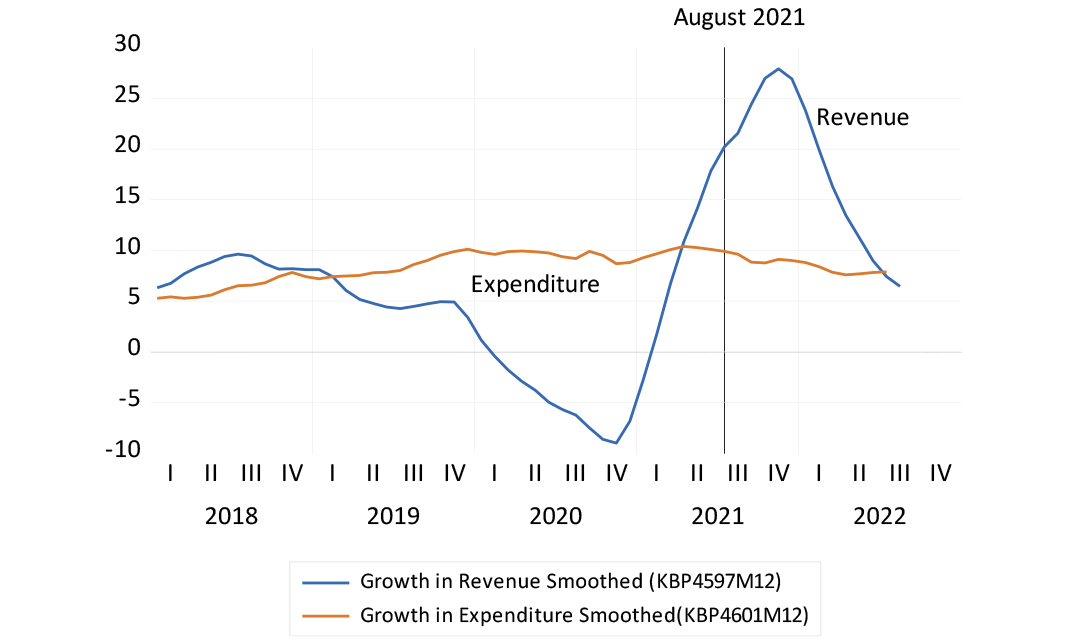

The global inflation of metal prices nevertheless has come as a most welcome boost to our economic prospects. It has boosted incomes earned and taxes paid by the mining sector. Revenue banked this fiscal year may be of the order of R160bn (running more than 20% ahead of last year’s R1.4 trillion Budget estimate), with more revenue to be expected next year. The Minister of Finance in his updated Budget Statement of November 2021 (MTBPS) recognised an extra R120 billion of revenue, which may well be too conservative. He also decided to use much of the extra revenue to borrow less rather than spend more. This should be helpful for the economy and its credit rating over the long run, but it represents a degree of fiscal austerity in the short term.

Growth in national government revenue and expenditure (annual growth, smoothed and extrapolated)

Source: SA Reserve Bank and Investec Wealth & Investment, 18 November 2021

Ideally, this windfall should be used to strengthen the economy over the long term. Extra consumption spending by well-paid government employees or improved welfare benefits is not advised. The government, simply by borrowing less, could strengthen the national balance sheet and improve our credit rating. Lowering tax rates would add to our economic potential.

So would allocating an extra R200bn to earmarked infrastructure funds – capital invested to generate extra revenue from supplying additional water, electricity, pipelines, port capacity and toll roads. All are desperately needed and are projects that users would pay enough to justify the extra spending. These funds ideally would welcome and attract additional private sector contributions of equity and loan capital.

About the author

Prof. Brian Kantor

Economist

Brian Kantor is a member of Investec's Global Investment Strategy Group. He was Head of Strategy at Investec Securities SA 2001-2008 and until recently, Head of Investment Strategy at Investec Wealth & Investment South Africa. Brian is Professor Emeritus of Economics at the University of Cape Town. He holds a B.Com and a B.A. (Hons), both from UCT.

Get Focus insights straight to your inbox