With great fanfare, Swedish super group Abba announced in September that it was making a comeback, some 40 years after breaking up. The comeback will involve an album release called Voyage and a special concert experience in London in May that features digital versions of the band members.

Mamma mia, here we go again

Abba isn’t the only 1970s phenomenon people are talking about. Another one is grabbing the headlines and it’s unlikely to make anyone nostalgic for the past – inflation. Spurred by excess demand and supply chain blockages, prices of all sorts of commodities, from energy to metals to foodstuffs, have been rising to multi-year highs. As a result, both producer and consumer inflation rates have soared, even in countries that have grown used to very low levels of inflation.

Spurred by excess demand and supply chain blockages, prices of all sorts of commodities, from energy to metals to foodstuffs, have been rising to multi-year highs.

Partly, the rise reflects what economists call base effects. Because inflation rates are expressed as a percentage change from a year before, the numbers over the last few months have looked particularly high, simply because of the collapse in prices due to falling demand during the most severe of the lockdowns last year. Oil futures, for example, fell into negative territory in April last year.

For this reason, central banks such as the US Federal Reserve have been talking about the transitory nature of the currently high levels of inflation. The inflation rates we are seeing in the world’s leading economies, according to this thesis, reflect the ongoing disruptions to consumer behaviour and supply chains, because of the pandemic. These should hopefully dissipate as the global economy returns to normal.

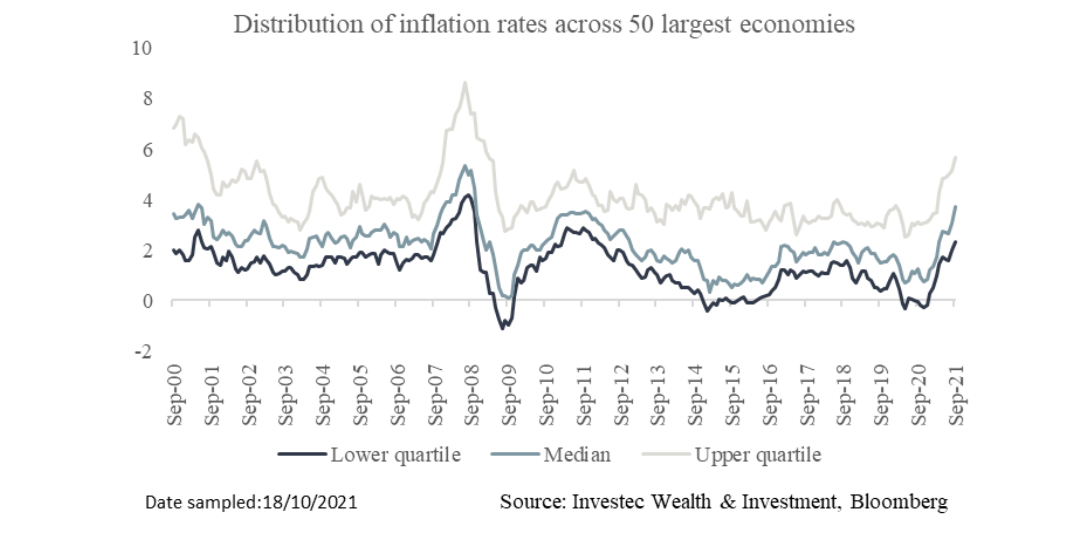

Figure 1: Global inflation picking up

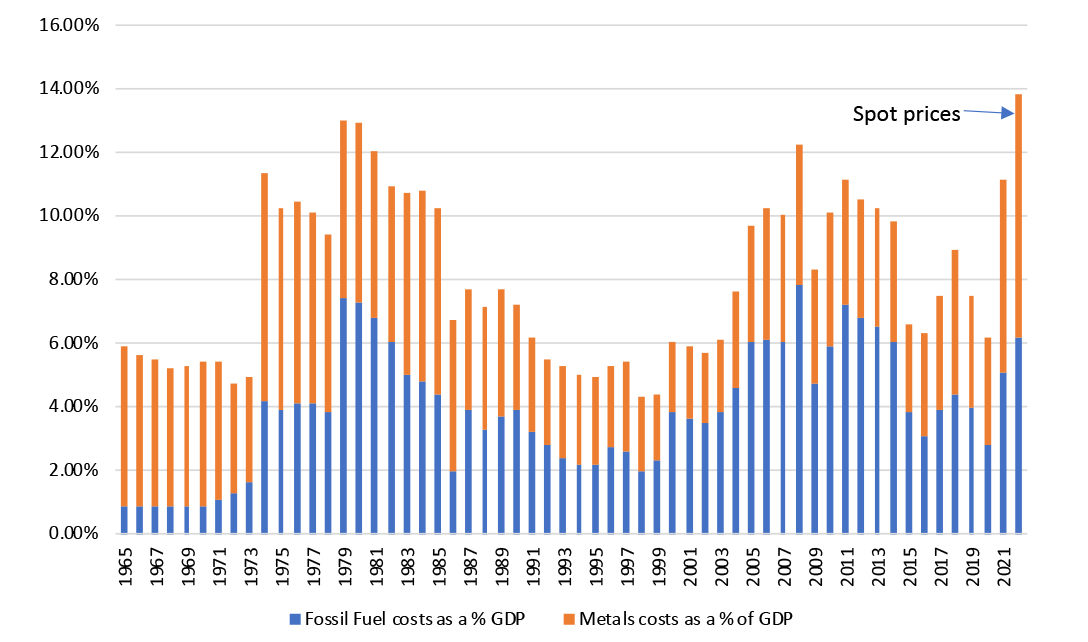

For example, in response to severe lockdowns and the collapse in demand last year, many suppliers cut back on production and distribution. At the same time however, stimulus measures in many of the world’s leading economies, which involved direct payments to households on a massive scale, resulted in a build-up of cash in people’s pockets and bank accounts. Consumers soon started to look for something to spend it on. Their mobility curtailed, consumers who previously would have spent a major portion of their disposable income on services or activities like travelling, the cinema or night clubbing, were now spending more of their money on goods. More demand for goods of course means more demand for the commodities that go into them, either directly as materials or indirectly as fuel used to transport them. It also means more demand for workers to make, transport and distribute them. These effects are being seen in the rising contribution by metals and energy to global GDP and spending.

Figure 2: The cost of raw materials as a percentage of GDP

Source: Bernstein, Investec Wealth & Investment, October 2021

And I think it’s gonna be a long, long time

As restrictions are lifted, Sars-Cov-2 vaccination rates increase and mobility rates rise, so we should expect a sense of normality to prevail. Stimulus cheques will no longer be sent to pay people to stay at home and service expenditure will regain its former share of wallet. Supply chain dynamics will go back to normal and pressures will dissipate. People will leave home to take up jobs in logistics and other services. Or so we hope.

Some market commentators are less sure however. Nouriel Roubini, from New York University’s Stern School of Business, points to a number of trends that he believes will be longer lasting and contribute to another phenomenon that the 1970s became known for, the combination of rising prices and sluggish growth – also known by the portmanteau ‘stagflation’ (The Stagflation Threat Is Real – Nouriel Roubini, Project Syndicate, 30 August 2021).

One of these trends, which had already started before Covid-19, is increasing deglobalisation and protectionism among the world’s leading economies. Countries are likely to strive to be less dependent on their trading partners, imposing tariffs on imports and restricting immigration. Companies will look to ‘reshore’ activities previously managed overseas, while countries may also look to hoard strategic products such as key metals and microchips.

Countries are likely to strive to be less dependent on their trading partners, imposing tariffs on imports and restricting immigration.

Many of these new trends will be propelled by the new Cold War between the US and China. On this score, it is interesting to note that US President Joe Biden has not made major changes to the tariffs introduced by his predecessor, Donald Trump.

Populism, another trend in place from before the pandemic, will drive many of these trends, Roubini argues. It will also keep government spending high as the backlash against inequality – exacerbated in many instances by the pandemic – intensifies. Governments will find it hard to reduce spending despite already high levels of debt.

Climate change could also spur inflation, in two ways. One is through disruptions such as droughts or extreme weather events like tropical storms that undermine production and logistics of key goods and commodities. The other is through the costs of climate change mitigation, which in turn manifests in two different ways. Firstly, this is through the costs of investing in non-carbon emitting forms of energy and in particular the metals and other products needed for a decarbonised future; and secondly through the reduced investment in fossil fuels as a result of this, which is ironically likely to drive up the cost of fossil fuels in the short to medium term.

When will I see you again?

Is Dr Doom (as Roubini is sometimes known) being overly pessimistic? To answer that question, we should perhaps look a little more closely at the years of high inflation of the 1970s. The period was remarkable for how long inflation remained entrenched in many leading economies over that period. On the face of it, the two main drivers of persistent inflation over that time were the two large energy crises of 1973 and 1979, which caused major fuel shortages and spikes in prices.

A closer look reveals a different story however. According to a paper by the European Central Bank (The “Great Inflation”: Lessons For Monetary Policy, ECB Monthly Bulletin, May 2010), inflation was already on the rise in the mid to late 1960s in the US, years before the energy crises had such a devastating effect. In the post-war years, the orthodoxy of US fiscal and monetary policy was to strive for full employment, even if this meant tolerating a little bit of inflation (the so-called Phillips Curve). Hence there was little alarm when prices started to rise.

Even when inflation rose further, the Federal Reserve was generally reticent to raise rates decisively. This was the case even after the collapse of the Bretton Woods agreement in the early 1970s, meaning that, according to the ECB paper, a “case has been made that OPEC’s oil price increases of 1973 and 1979 could only have occurred under the conditions of global liquidity expansion associated with the collapse of Bretton Woods”.

You can go your own way

The ECB paper contrasts the US experience with that of Germany. While Germany saw inflation rates rise in the 1970s, it was never to the extent of that seen in the US. Unlike the Federal Reserve and other major central banks, the Bundesbank adopted a policy of monetary targeting, which helped it to not only control demand through its interest rate settings, but to anchor inflation expectations.

In the end, it took a series of aggressive rate hikes by the Federal Reserve under Paul Volker to usher in a long period of low inflation that started in the early 1980s.

(Interestingly, SA continued to experience high inflation in the 1980s, even as it receded in its major trading partners. Faced with sanctions and a debt standstill, SA kept rates low in an attempt to stimulate domestic growth. It took the arrival of Governor Chris Stals, following the orthodoxy of the Bundesbank and Volker, to eventually bring inflation in the 1990s down to single digits).

Don’t worry about a thing

Perhaps the lesson of the 1970s is for central banks to act decisively when they see signs of inflation entrenching itself at higher levels. There’s an understandable worry that, after so many years since the Global Financial Crisis of 2008 of low rates and quantitative easing, central banks will be reticent to make the big calls when the time comes.

Yet the statements by central banks so far have not indicated any sense of complacency about rising prices. The Federal Reserve seems on track to start unwinding its asset purchase programme in November and a hike in rates could come as early as next year. A number of central banks have already started to hike rates – including the likes of Mexico, Brazil, Chile, the Czech Republic, Norway, Russia, Poland, New Zealand and Hungary.

What about the non-monetary aspects of inflation? A recent article by The Economist notes that cost-of-living adjustments and union-wide wage bargaining, which were a commonplace in developed economies in the 1970s, are less common today, meaning that there is less scope for inflationary increases in wages to become entrenched.

Productivity is also at higher levels than seen in the 1970s, notes The Economist. This may even increase if countries roll out infrastructure projects. At the same time, the withdrawal of Covid-related assistance programmes may also dampen consumer spending.

Technology will also help to drive productivity and contain inflation. Manufacturers will find ways to use less material in manufacturing goods and the investment in decarbonisation should eventually translate into improved productivity. Advances in 3D printing could minimise the need to transport finished goods over large distances. Artificial intelligence and the internet-of-things will make supply chain logistics smarter and less vulnerable to bottlenecks. More and more of the goods we consume will be intangible (think of how the delivery of music has moved over the years from vinyl to CDs to streaming services).

It may take years for these technological advances to have an impact. But they do show that higher inflation is neither inevitable nor necessary long lasting.

About the author

Patrick Lawlor

Editor

Patrick writes and edits content for Investec Wealth & Investment, and Corporate and Institutional Banking, including editing the Daily View, Monthly View, and One Magazine - an online publication for Investec's Wealth clients. Patrick was a financial journalist for many years for publications such as Financial Mail, Finweek, and Business Report. He holds a BA and a PDM (Bus.Admin.) both from Wits University.

Receive Focus insights straight to your inbox