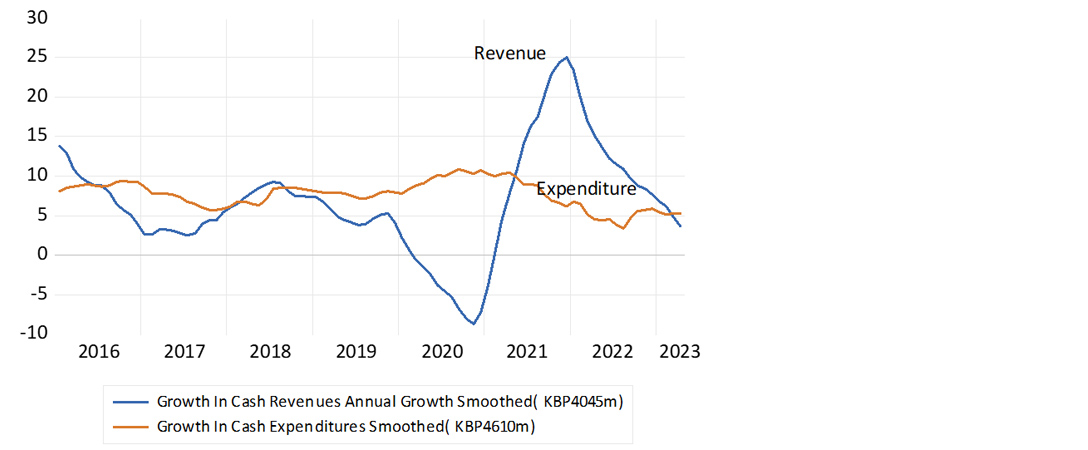

A shortfall in South African government revenues has provoked something of a fiscal contretemps. The government has raised R60bn less revenue than was estimated in the February Budget. This followed the large windfall in 2021 that was linked to the post-Covid inflation of metal prices. The recent pullback in metal prices and mining company profits has seen government revenues falling back sharply from peak growth rates of 25% in late 2021 to zero growth now. Government expenditure has stayed at an essentially modest growth rate of about 5% a year.

Recent trends in government revenues and expenditure

Source: SA Reserve Bank and Investec Wealth & Investment, 22/09/2023

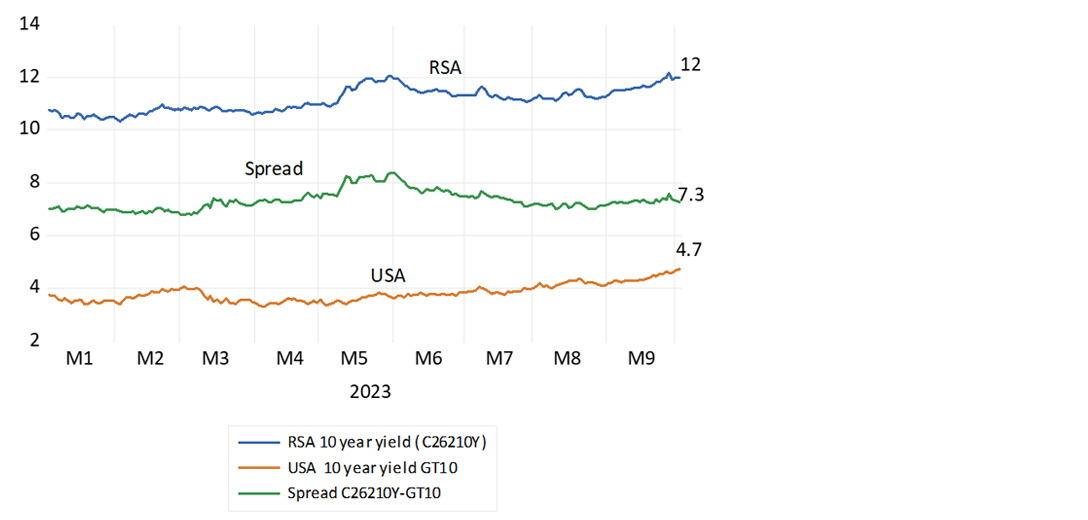

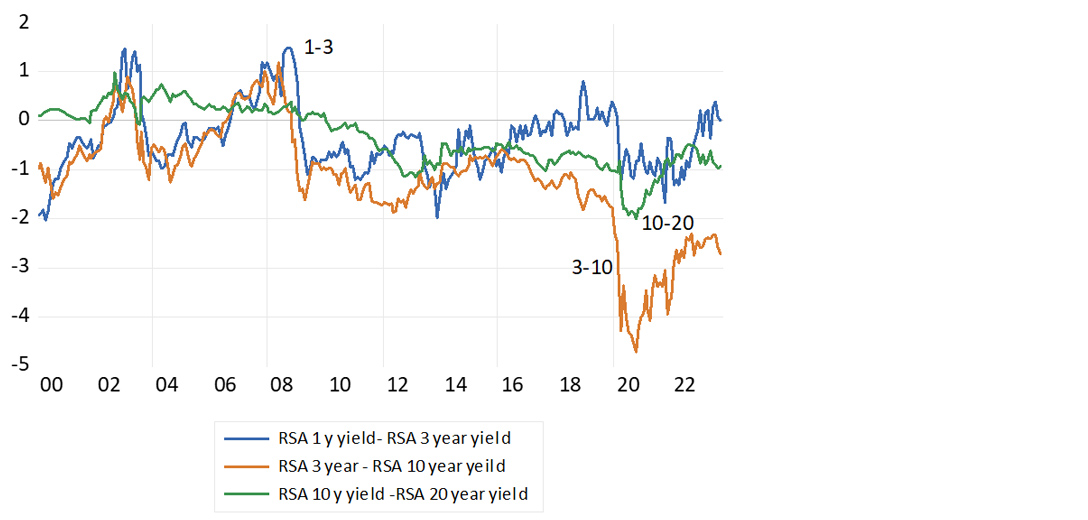

Less revenue means more borrowing. South African taxpayers are already paying a high price for our highly compromised credit rating. We pay an extra 2.7% more than Uncle Sam to borrow US dollars for five years. Towards the end of last month, the rand-denominated SA government (RSA) five-year bond offered investors 5.5 percentage points more than a US Treasury of the same duration (9.89% minus 4.39%). The spread on a 10-year RSA over the US Treasury yield was even higher and was at 7.3 % (12% minus 4.70%) on 3 October. The reason for such expensive (after expected inflation, borrowing costs and risk spreads) is the persistent scepticism on the part of potential investors, about the willingness and consequences of South Africa having to live within the limits of government revenue that is expected to be heavily constrained by very slow economic growth. The further forward lenders are asked to judge our growth prospects and fiscal policy settings, the wider have been the risk spreads and the higher the cost of issuing long-dated debt (what is called the “term premium” in the market jargon). We should add that the recent pressure on RSA yields has come from the strong upward move in the key US Treasury yields. The spread between the bond yields, while wide, has not increased in response to the news about declining South African tax revenues.

SA and US 10-year bond yields and risk spread

Source: Bloomberg and Investec Wealth & Investment, 22/09/2023

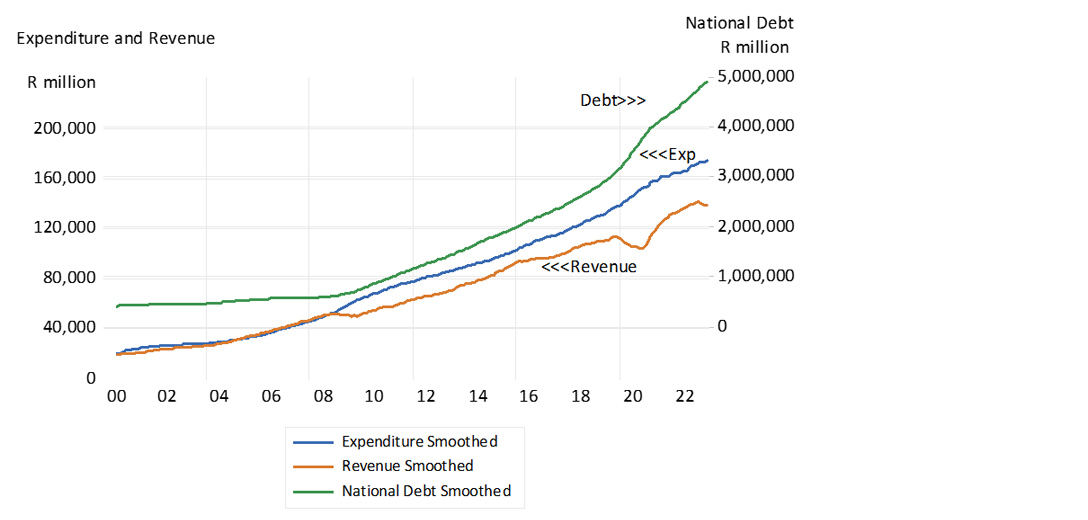

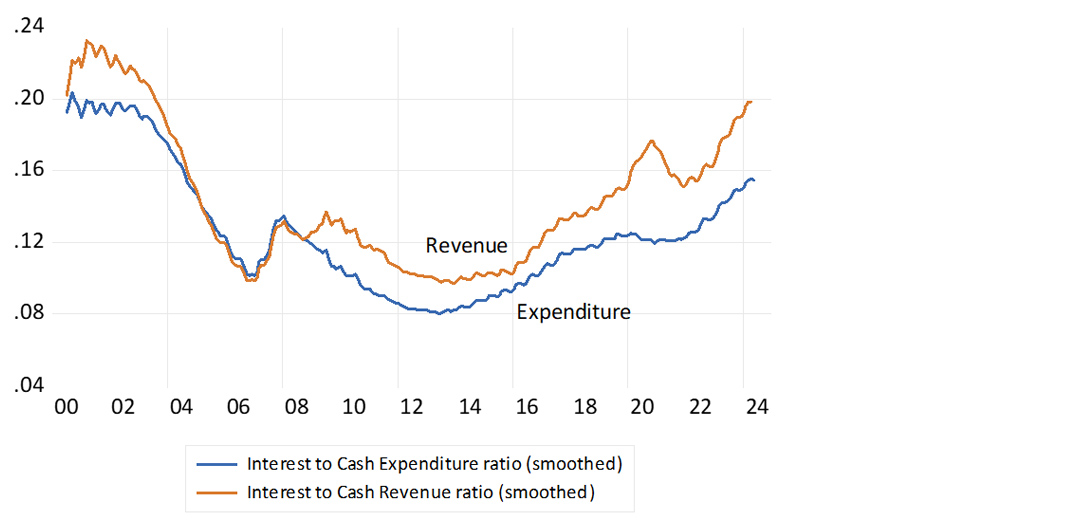

If there is a crisis in the bond market, then the burdens of raising debt on the taxpayer have been a long time in the making. Government revenues have consistently lagged spending, by a percent or two each year ever since the recession of 2010. The Covid-19 lockdowns were also naturally harder on revenues than government expenditure. These differences between revenue and expenditure have had to be covered by large volumes of additional government borrowing. The share of interest paid by the national government in revenues and expenditures has been rising sharply, doubling since 2014. Interest paid in serving the national debt is now 20% of all national government revenues and about 16% of all expenditures. It is not the kind of expenditure that helps to win elections.

Government revenue, expenditure and debt

Source: SA Reserve Bank and Investec Wealth & Investment, 22/09/2023

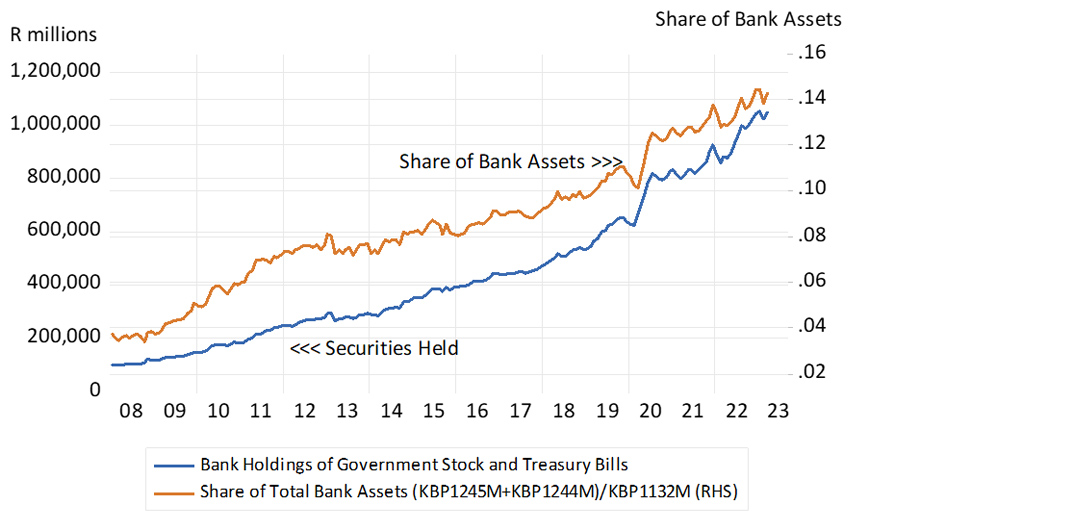

South African banks are now funding more of the national debt. In 2008 the share of government stock and Treasury bills was a mere 4% of all bank assets – this ratio is now 14%. After 2020, and as the fiscal deficit widened with less revenue and more post-Covid spending, the banks have increased their loans to the government by R600bn, mostly of short-term duration. The banks have thus substituted lending to the government for lending to the private sector, understandably so given the weakness of demand for credit by the private sector.

This has inflationary potential. Relying on banks to fund government expenditure when supported by abundant cash reserves supplied by the Reserve Bank may well lead to excess supplies of deposits (ie money) in the system. This is because banks lend more to the government on a scale that could become inflationary. If it leads to excess supplies of money, higher prices could follow as these excess supplies of money are exchanged for goods and services. These money supply effects of extra lending and spending apply as much to government borrowing from the banks as they would to private sector borrowing and spending that finds its way into extra bank deposits.

The banks now hold substantial sums of excess cash reserves with the Reserve Bank, which encourages this through the interest it pays on these reserves. It has become the policy-determined rate that sets the basis for all short-term interest rates. The SA Reserve Bank, like the Fed, believes it can control the demand for such cash reserves through its interest rate settings. By setting the right level of interest rates it pays on these reserves, it believes it will prevent the banks from turning cash into additional loans that end up as extra deposits as the loans are drawn down. It is a new world of monetary policy experimentation and it will be a space worth watching.

Holdings of Treasury bills and government stock by banks

Source: SA Reserve Bank and Investec Wealth & Investment, 22/09/2023

Interest payments as a share of government revenue and expenditure

Source: SA Reserve Bank and Investec Wealth & Investment, 22/09/2023

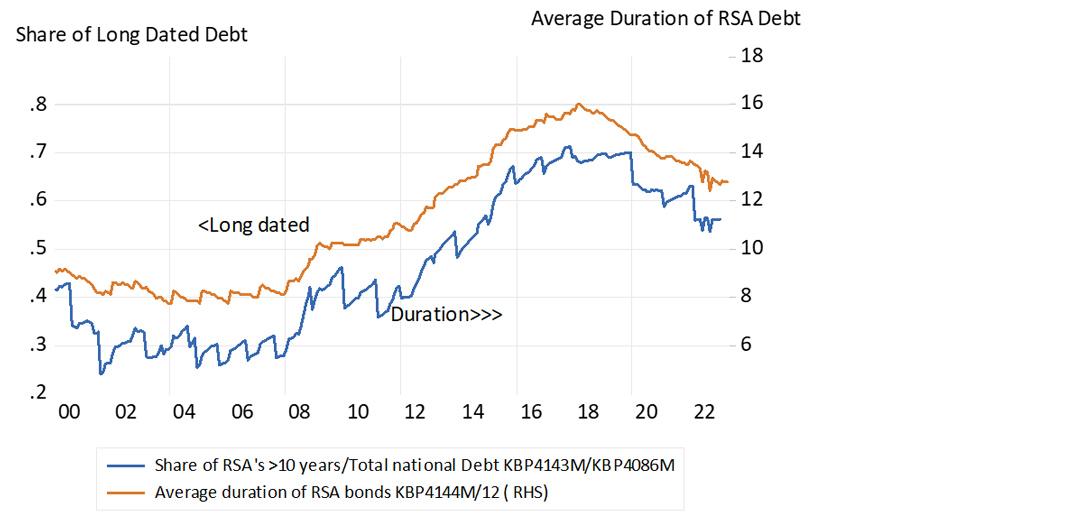

The share of government debt with a maturity of more than 10 years has risen strikingly, from 30% to over 70% of all national government debt between 2008 and 2020 – at inevitably higher rates. The government could immediately relieve part of the burden of high interest rates by reducing the extraordinarily long duration of its debt, as indeed it has been doing since 2018.

Long-dated debt as a share of total debt and the average duration of all debt

Source: SA Reserve Bank and Investec Wealth and Investment, 22/09/2023

Bond yield differences by duration

Source: Iress and Investec Wealth & Investment, 22/09/2023

It was a form of hubris to think that lenders would be willing to take a 20-year or longer view of the fiscal outlook for South Africa without compensation. The long-term lender is highly exposed to inflation, which the short-term lender largely avoids. The benefit of borrowing long is that it avoids the risks attached to having to roll over short-term debt at inconvenient moments in the money market. However, this made less sense when National Treasury was building its cash reserves at the Reserve Bank, from R70 billion in early 2010 to R183 billion by January this year.

Managing the interest payment burden of national debt can play a small part in solving the problem of slow growth for the government. This is the case even if government and private spending remain constrained in real terms this year and next. Only faster growth can avoid the interest rate trap, however, since interest paid/all government spending should rise further. Absent growth, the burden of paying interest, rather than undertaking other forms of spending, is likely to make a resort to money creation irresistible. The growth-enhancing choices for economic policy should be obvious. There is no other way.

About the author

Prof. Brian Kantor

Economist

Brian Kantor is a member of Investec's Global Investment Strategy Group. He was Head of Strategy at Investec Securities SA 2001-2008 and until recently, Head of Investment Strategy at Investec Wealth & Investment South Africa. Brian is Professor Emeritus of Economics at the University of Cape Town. He holds a B.Com and a B.A. (Hons), both from UCT.

Get Focus insights straight to your inbox

Disclaimer

Although information has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable, Investec Wealth & Investment International (Pty) Ltd or its affiliates and/or subsidiaries (collectively “W&I”) does not warrant its completeness or accuracy. Opinions and estimates represent W&I’s view at the time of going to print and are subject to change without notice. Investments in general and, derivatives, in particular, involve numerous risks, including, among others, market risk, counterparty default risk and liquidity risk. The information contained herein is for information purposes only and readers should not rely on such information as advice in relation to a specific issue without taking financial, banking, investment or other professional advice. W&I and/or its employees may hold a position in any securities or financial instruments mentioned herein. The information contained in this document does not constitute an offer or solicitation of investment, financial or banking services by W&I . W&I accepts no liability for any loss or damage of whatsoever nature including, but not limited to, loss of profits, goodwill or any type of financial or other pecuniary or direct or special indirect or consequential loss howsoever arising whether in negligence or for breach of contract or other duty as a result of use of the or reliance on the information contained in this document, whether authorised or not. W&I does not make representation that the information provided is appropriate for use in all jurisdictions or by all investors or other potential clients who are therefore responsible for compliance with their applicable local laws and regulations. This document may not be reproduced in whole or in part or copies circulated without the prior written consent of W&I.

Investec Wealth & Investment International (Pty) Ltd, registration number 1972/008905/07. A member of the JSE Equity, Equity Derivatives, Currency Derivatives, Bond Derivatives and Interest Rate Derivatives Markets. An authorised financial services provider, license number 15886. A registered credit provider, registration number NCRCP262.