That the SA economy has performed quite as poorly as it has in recent years is not easily explained. The rate of growth of less than 2% a year represents a very low hurdle to leap, with little prospect of any lift-off, according to the economic forecasters in and outside government.

Yet there are more corrupt economies with poorer endowments that grow faster. The SA economy, after all, operates largely according to the dictates of a market economy, where businesses openly compete for their share of household budgets and, in general, appear to be profitable enough to survive without notable strain on balance sheets. The quality of the services they provide is not found wanting by the standards of peer group economies.

The barriers to foreign direct investment – or controls on their freedoms to pay dividends or repay capital – are not especially inhibiting by global standards. These foreign-owned and managed firms play an important role in the economy, though we could do with more of them. Their reluctance and those of their local competitors to invest more of their internally generated savings, rather than pay dividends or borrow more, or else raise more equity capital to grow their enterprises, points to slow growth now and in the future.

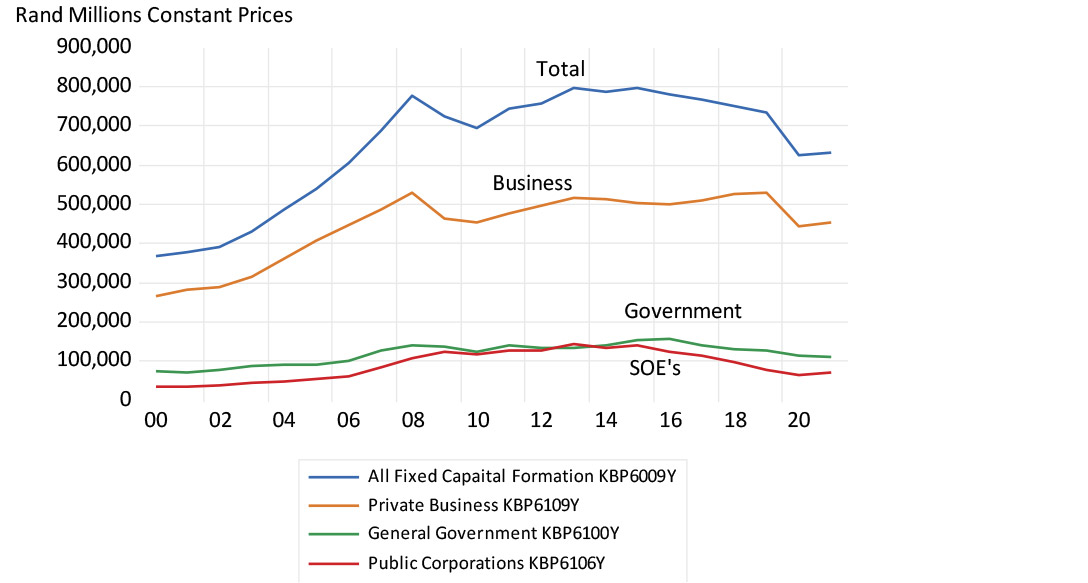

The low ratio of capex to GDP and its recent abrupt reduction is a key feature of a stagnant economy. After all, less invested today means less output and employment tomorrow. It describes slow growth but does not explain the reluctance to grow capacity. SA business generally may be described as, at best, being in a holding pattern. The clear reluctance to invest in future output, income generation and workforce, needs to be understood and addressed if the outlook for the economy is to improve.

Figure 1: Fixed capital formation at constant 2015 prices

Source: SA Reserve Bank and Investec Wealth & Investment, 25/04/2022

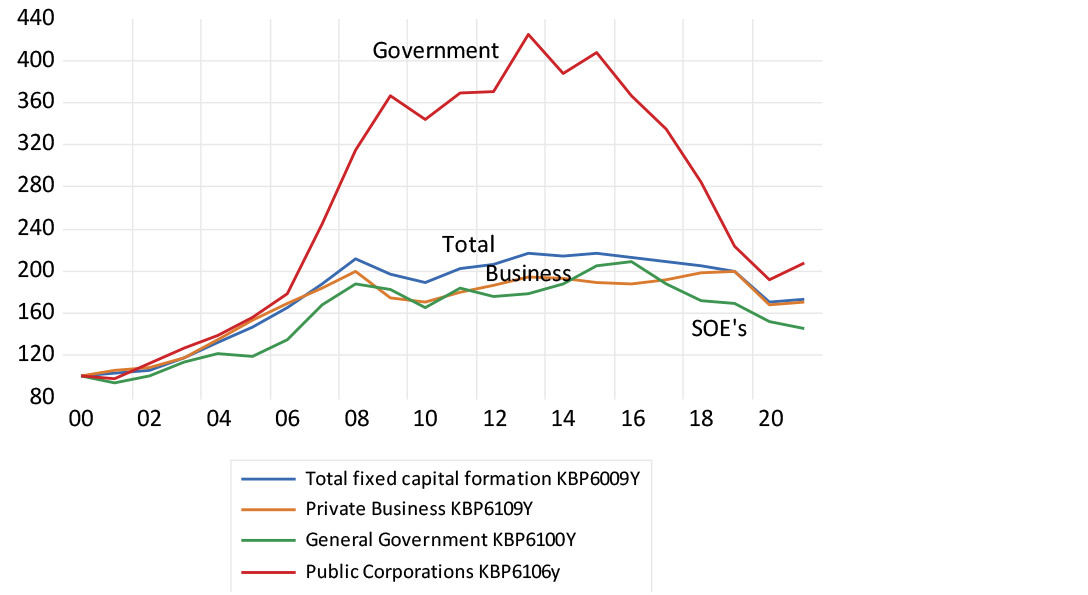

Figure 2: Total real fixed capital formation, 2000-2020 (2000 = 100)

Source: SA Reserve Bank and Investec Wealth & Investment, 25/04/2022

We need look no further for a large part of the explanation of pedestrian growth than to the now highly conspicuous and abject failures of the SA public sector in almost all of its guises. No business or household is a self-sufficient island. They depend on collectively supplied services to operate effectively. The old and new SA relied and relies heavily and unwisely on the state as a producer of essential services, including electricity, water, transport (including ports) and education, through the state-owned enterprises (SOEs). The inability of Eskom to meet depressed demand for electricity set limits to growth, as do the failures of Transnet to run the railways and ports anything like competently for their users. The failures of almost all of the SOEs to allocate resources adequately have meant large amounts of waste and diminished growth potential.

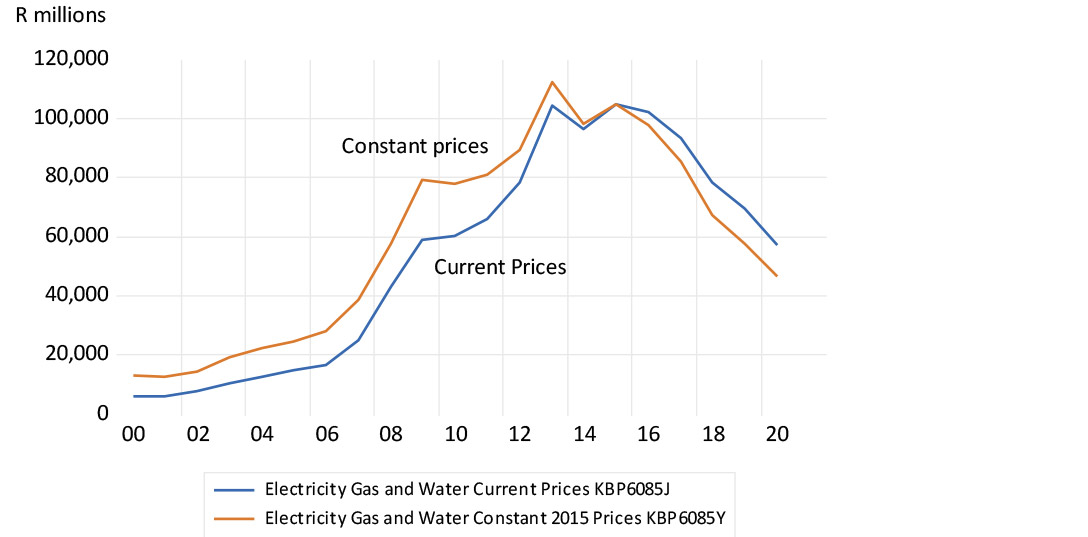

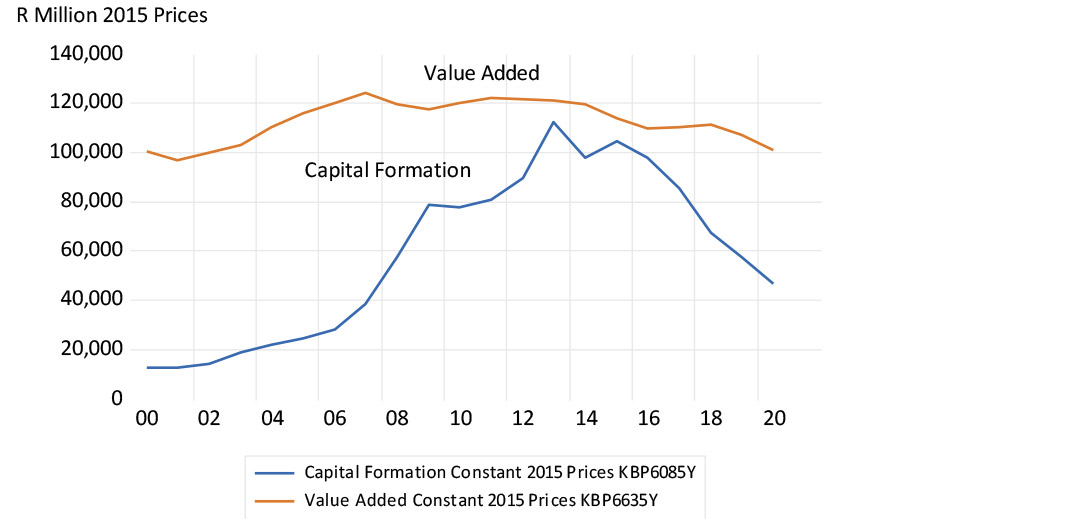

The relationship between what has been spent on the large new electricity-generating stations Medupi and Kusile and what has come out as additional electricity is especially egregious and damaging. As much as R1.1 trillion was invested in electricity, water and gas between 2000 and 2021, much of it in electricity generation. Shockingly, the real output of electricity, etc. have declined by 20% since 2000. If Eskom were privately owned the losses, would have to be borne by shareholders, not its customers.

Figure 3: Electricity, gas and water – capital formation in constant (2015) and current prices

Source: SA Reserve Bank and Investec Wealth & Investment, 25/04/2022

Figure 4: Electricity, gas and water – capital formation and value-added in constant (2015) prices

Source: SA Reserve Bank and Investec Wealth & Investment

Other government agencies have also failed. Provinces and, in particular, municipalities have failed to maintain the quality of the services they provide, to maintain their infrastructure and add to it. Their failure has also become destructive to economic opportunities for businesses and households, which are dependent on the provisions of key services such as water, roads, sewage, development, building plans, education and training, at reasonable costs to the tax or ratepayers. Such failures are reflected in the declining real value of the homes South Africans own – representing a large percentage of the wealth of the average household – which has made them less able and willing to demand goods and services from SA businesses.

The ever more conspicuous failures of the public sector to deliver the basics at a reasonable cost have come to a conspicuous head. Hopefully, the economy will not continue on a path of failing to improve the living standards of all South Africans, especially the poor who are increasingly dependent on welfare provided by constrained taxpayers. Restructuring their operations and ownership structures, and changing the management incentives of the public sector is an obvious and urgent requirement for growth, as is reducing the reliance on the public sector to deliver the essentials.

But more importantly, we need a meta explanation of why the public sector has failed South Africans so badly since the advent of democracy. What’s required is an explanation that might account for SA’s, especially poor performance. The answer to all questions of economic outcomes is to be found in the incentives offered to those leading and working for any economic agency. It is an economic truism that you get what you pay for. Managers and workers should deliver what they are paid to deliver. If we observe the SA public sector, the key political objective on which its performance is evaluated is not the efficient use of resources, with delivery-related rewards for the officials held responsible within constrained sensible budgets.

The key objective they have had to meet has been the transformation of the public sector workforce. Worthy as this objective may appear, it has come at great cost, including to the poor, who depend so heavily on the state, directly and indirectly.

About the author

Prof. Brian Kantor

Economist

Brian Kantor is a member of Investec's Global Investment Strategy Group. He was Head of Strategy at Investec Securities SA 2001-2008 and until recently, Head of Investment Strategy at Investec Wealth & Investment South Africa. Brian is Professor Emeritus of Economics at the University of Cape Town. He holds a B.Com and a B.A. (Hons), both from UCT.

Get Focus insights straight to your inbox