The Nobel Prize for economics was recently awarded to former Fed Chair Ben Bernanke and two other American economists, Douglas Diamond and Philip Dybvig. The award was for their analysis that helped overcome the Global Financial Crisis of 2008-09. Which is fair enough. However, the award honouring central bank judgement ironically comes at a time when central bankers are struggling to cope with a more recent crisis, caused by the Covid-19 lockdowns, its inflationary aftermath and the still more recent shock to energy prices caused by the war in Ukraine.

There are many precedents for the best way to deal with a banking crisis, which boil down to printing more money. There are no obvious precedents for the best way to deal with the lockdowns that were accompanied by an even larger increase in the money supply. Having said that, a glance at monetary history, especially at what happens to economies when wars break out, would have told us that the post-Covid acceleration in spending and prices should not have come as a surprise. The Fed could have done with a little more acquaintance with monetary history.

The participants in financial markets responsible for managing the accumulated savings of their communities have had difficulty in anticipating the recent central bank actions and their consequences. The agreed task of central banks is to make it easier for the market to do so. Yet the prospect of a recession, as policy-determined interest rates have been pushed dramatically higher – with more increases to follow – has loomed ever larger. This confusion does no credit to central bankers.

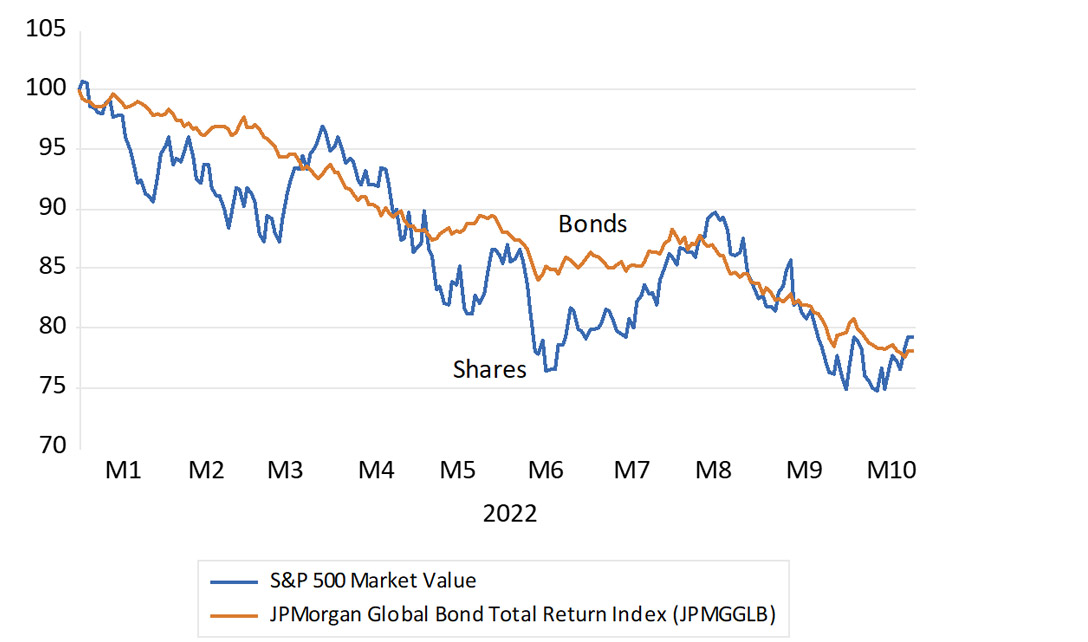

The destruction of hard-earned wealth has occurred on a devastating scale. The benchmark S&P 500 has lost 20% of its value (or US$8.7 trillion) since the start of the year. The larger portfolios of government bonds have suffered even greater losses in US dollars. The global government bond index is also about 20% weaker, year-to-date.

Performance of global equities and bonds in US dollars (1 January 2022 = 100)

Source: Bloomberg and Investec Wealth & Investment, 25 October 2022

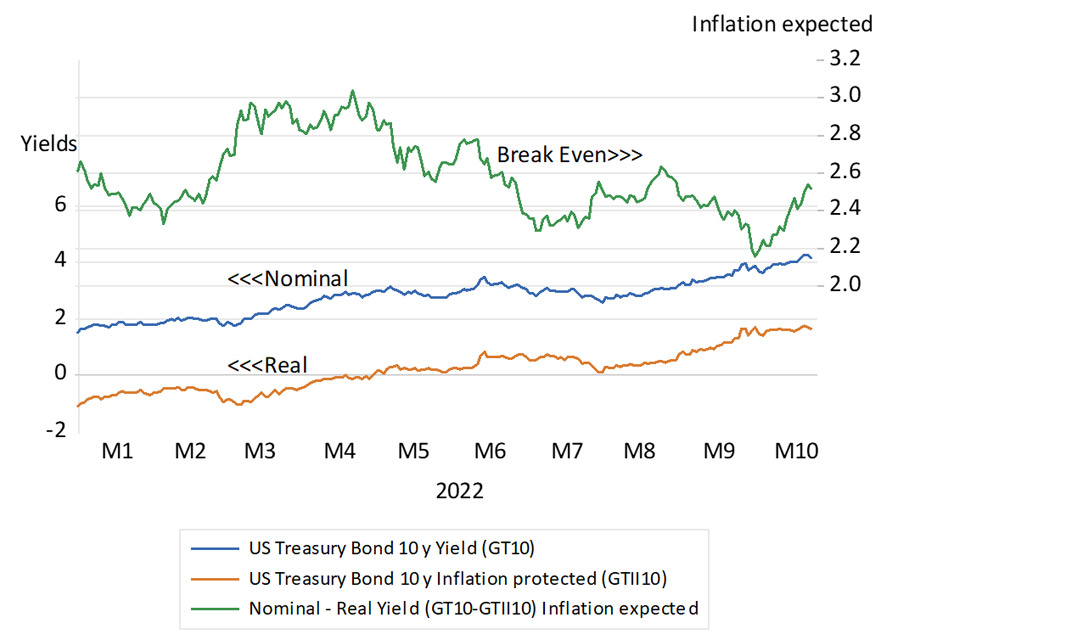

The most surprising feature of recent market moves has been the failure of the bond markets to provide the protection for portfolios that they usually do. The safe haven has been to hold US dollars on very short maturities. Moreover, US long bond yields have increased not because more inflation is expected. It has been the real yields on inflation protected government securities (TIPS) that have moved higher, reducing the gap between real and nominal yields that represent compensation for assuming inflation risks in bond portfolios.

The market now expects inflation to average 2.5% a year over the next 10 years, in other words less inflation in the US than it expected earlier in the year, and little more than the 2% a year average rates of inflation over the next 10 years, which is the Fed target. So why the panic at the Fed? And why has the real cost of capital risen when the outlook for growth has deteriorated and the value of capital has fallen? Nobel prizes will be on offer for anyone who comes up with good answers to these conundrums.

US 10-year Treasury yields (nominal and real)

Source: Bloomberg and Investec Wealth and Investment, 17/08/2022

The Fed and other central banks will argue that the economic pain is necessary to avoid currently elevated inflation rates becoming embedded in their economies. However the theory that inflation is simply an extrapolation of past inflation is inconsistent with economic rationality and without evidence to support it. Supply side shocks, for example an oil or gas embargo, that can cause the CPI to rise, are temporary. They pass through unless more money is created to sustain demand at higher prices.

Inflation can only perpetuate itself when the supplies of money and credit are allowed to increase continuously in response to higher prices (whatever their cause). We then understandably expect them to carry on doing so to sustain higher rates of inflation. This is the case in many countries where printing money to fund government expenditure becomes an expected norm. This is not (yet) the case in Europe or the US, where the money supply is already in decline and where demand has already weakened enough to take the demand-side pressure off prices. The market appears to recognise this even though the central banks appear not to. An inflation reality check is on the way; the sooner the better.

About the author

Prof. Brian Kantor

Economist

Brian Kantor is a member of Investec's Global Investment Strategy Group. He was Head of Strategy at Investec Securities SA 2001-2008 and until recently, Head of Investment Strategy at Investec Wealth & Investment South Africa. Brian is Professor Emeritus of Economics at the University of Cape Town. He holds a B.Com and a B.A. (Hons), both from UCT.

Get Focus insights straight to your inbox

Disclaimer

Although information has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable, Investec Wealth & Investment International (Pty) Ltd or its affiliates and/or subsidiaries (collectively “W&I”) does not warrant its completeness or accuracy. Opinions and estimates represent W&I’s view at the time of going to print and are subject to change without notice. Investments in general and, derivatives, in particular, involve numerous risks, including, among others, market risk, counterparty default risk and liquidity risk. The information contained herein is for information purposes only and readers should not rely on such information as advice in relation to a specific issue without taking financial, banking, investment or other professional advice. W&I and/or its employees may hold a position in any securities or financial instruments mentioned herein. The information contained in this document does not constitute an offer or solicitation of investment, financial or banking services by W&I . W&I accepts no liability for any loss or damage of whatsoever nature including, but not limited to, loss of profits, goodwill or any type of financial or other pecuniary or direct or special indirect or consequential loss howsoever arising whether in negligence or for breach of contract or other duty as a result of use of the or reliance on the information contained in this document, whether authorised or not. W&I does not make representation that the information provided is appropriate for use in all jurisdictions or by all investors or other potential clients who are therefore responsible for compliance with their applicable local laws and regulations. This document may not be reproduced in whole or in part or copies circulated without the prior written consent of W&I.

Investec Wealth & Investment International (Pty) Ltd, registration number 1972/008905/07. A member of the JSE Equity, Equity Derivatives, Currency Derivatives, Bond Derivatives and Interest Rate Derivatives Markets. An authorised financial services provider, license number 15886. A registered credit provider, registration number NCRCP262.