There is a recognition in South Africa that welfare benefits of the type one finds in developed economies (such as a basic income grants) are impossible without developed economy social security taxes, of the order of a 10-15% salary sacrifice imposed on the formally employed.

However, higher taxes discourage growth by discouraging enterprise and encouraging the emigration of scarce skills and capital. Redistribution can also lead to slower growth, by reducing the incentive to be economically active. The numbers in South Africa of the not economically active (NEA) have been rising as disturbingly fast as the estimated unemployed. Many of those classified as unemployed are in fact NEA. They say they would be willing to work when asked, but only for what are unrealistically high rewards, and for work that is simply not available, particularly in the rural areas where the unemployment rates are double those in the urban areas.

The numbers in South Africa not economically active (NEA) have been rising as disturbingly fast as the estimated unemployed.

It is striking to note how little income the poorest South Africans earn from working. Of the 16.3 million people in the lowest fifth of the income distribution bands in 2016 (31% of the population of SA), only 15.9% were employed, and their unemployment rate was over 60%. About 53% were NEA. Their average monthly wage was R1,017. This contrasts with the R3,500 national minimum wage recommended by a special panel appointed by National Treasury. For the second poorest fifth (25% of the population), about 42% were NEA. Of the middle fifth, only 52.5% were then employed (NEA 33%) for an average monthly wage of but R2,651. Meanwhile, the national minimum wage is only exceeded by the workers in the top two fifths of the income distribution, 25% of the population.

Of course it should be noted that cash grants, housing supplied, subsidised utilities, education, hospitals and clinics have all helped meaningfully to relieve absolute poverty. They have allowed many of the poor to survive without work. It has also raised the wage at which it is sensible for many to work.

Unemployment of the order of 40% (and higher for the youngest cohorts of potential workers) cannot only be explained by a lack of demand for labour, the result of slow growth and the host of regulations and other factors that discourage demands for low skilled labour. This they surely do.

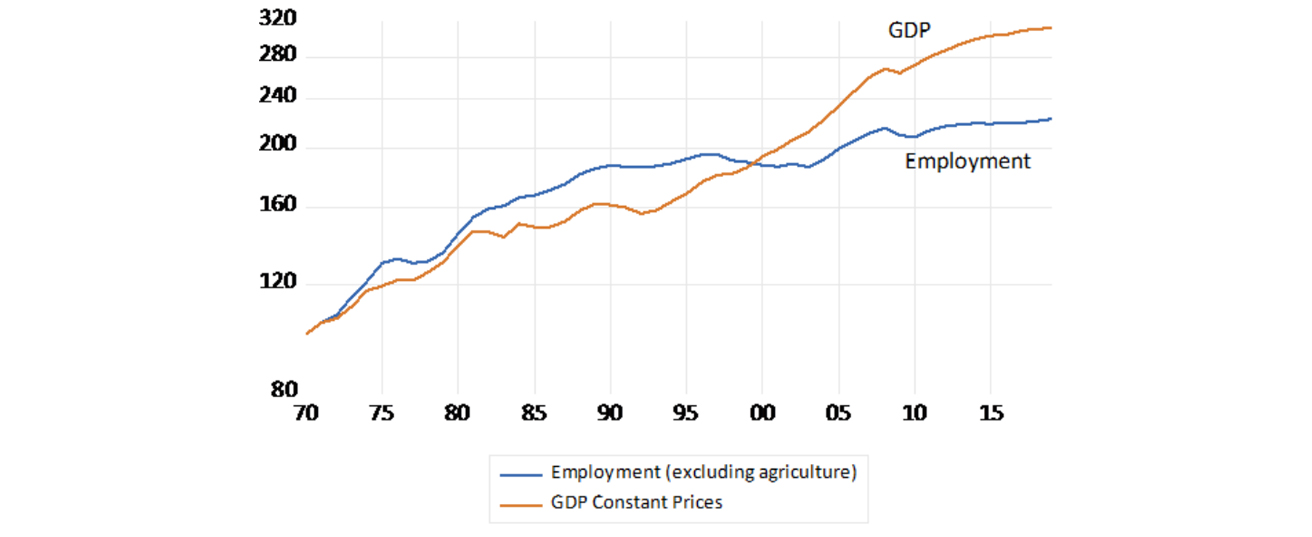

However, the relationship between GDP (growing slowly) and the numbers employed outside of agriculture has become much weaker since approximately 1990. Each percentage point of growth in GDP now results in fewer jobs created. Much improved poverty relief helps explain this trend.

Figure 1: GDP (constant prices) and employment outside agriculture (1970 = 100)

Source: SA Reserve Bank and Investec Wealth & Investment, September 2021

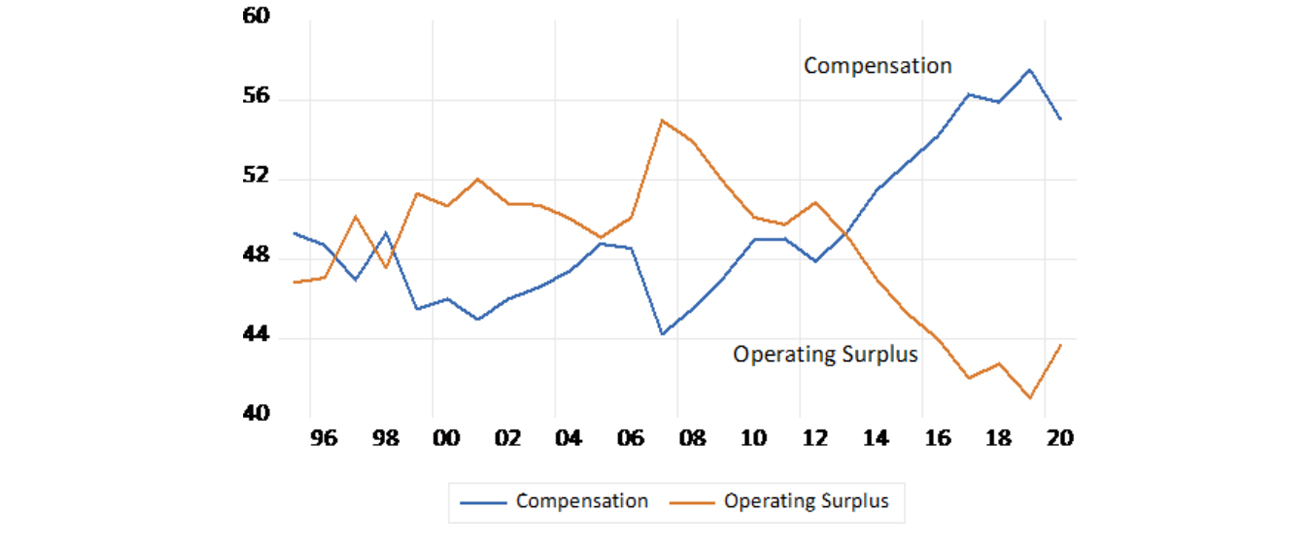

Yet the share of the economy received as wages and salaries has increased significantly in recent years, while the share of operating surpluses of the firms providing employment has shrunk. This is a worry, given the importance of profits for growth-enhancing investments in equipment and people. Those with better-paid jobs, the favoured and well-protected insiders of the developed sector of the SA labour market, have benefited. Meanwhile, the observed unemployment has not affected the active competition for skilled, better-paid workers.

Figure 2: Percentage share of gross value-added (current prices) compensation of employees and operating surpluses

Source: SA Reserve Bank and Investec Wealth and Investment, September 2021

South Africa has chosen to address poverty with welfare rather than with jobs. Further redistribution without growth is wishful thinking. It cannot solve the poverty problem and will exacerbate the unemployment problem. Educating and training the many potential entrants to the labour force so that they can command the rewards that make it sensible for many more to work, and sensible to hire more productive workers, will raise incomes and employment.

About the author

Prof. Brian Kantor

Economist

Brian Kantor is a member of Investec's Global Investment Strategy Group. He was Head of Strategy at Investec Securities SA 2001-2008 and until recently, Head of Investment Strategy at Investec Wealth & Investment South Africa. Brian is Professor Emeritus of Economics at the University of Cape Town. He holds a B.Com and a B.A. (Hons), both from UCT.

Get Focus insights straight to your inbox