Predictions are part and parcel of our everyday lives. Whether it’s minor decisions like picking a restaurant for dinner or major ones like buying a new house, making an investment or choosing a spouse – all involve some sort of forecast about the future. Will the food be good? Will my new house or investment go up in value? Will I live happily ever after with my chosen life partner?

Moreover, we set great store by the forecasts of highly qualified professionals to guide us in our decision making. Armies of pundits and experts have built careers around making predictions. These range from economists to political analysts to climate scientists and gurus in several other fields.

Despite their qualifications and the analytical tools at their disposal, it turns out that pundits are often no better at seeing the future – whether it’s the economy or global politics – than we are in making our own personal decisions. Frequently they are spectacularly wrong, yet we nonetheless continue to depend on them for making vitally important decisions.

The dart-throwing chimpanzee

Unfortunately, we humans are not usually very good at it. One famous 2005 study found that, over a 20 year period, a dart-throwing chimpanzee was as good a forecaster as the average expert in a broad range of fields (more on this further on).

Forecasters moreover appear to be prone to biases. My colleague in the UK, John Wyn-Evans, notes that analysts have a tendency to downgrade their earnings forecasts as a year unfolds – they have done so in 20 of the last 28 years (the median global annual earnings downgrade since 1988 has been 7%).

This points to a collective bias towards optimism at the start of each year – though in fairness, of those 20 downgrades, 12 have resulted in higher markets, so even in a downgrade year, it’s a toss-up whether markets rise or fall.

Similarly, august bodies like the International Monetary Fund (IMF) have also shown a bias towards downgrading in recent years. In April, the IMF World Economic Outlook projections for GDP growth, which are updated every quarter, showed a downgrade in just about every geography from the January projections, which in turn were down from October.

In that vein, since the financial crisis of 2008, actual US GDP estimates have consistently fallen short of projections.

Analysts have a tendency to downgrade their earnings forecasts as a year unfolds – they have done so in 20 of the last 28 years.

Perhaps as disturbing is that we continue to put our faith in the abilities of the professional forecasters. We seem to be drawn to those gurus who appear in the media making forthright predictions about how the political situation in a war-torn part of the world will unfold, or what a global strategist says about global growth or earnings. We seem to quickly forget their mistaken forecasts a year later, even as we soak up their brand new prognostications.

The above may leave one feeling despondent. The chimpanzee story made great copy for newspapers, but it was also depressing in a way. The story implied that forecasting was an exercise in futility and that we might as well toss a coin or hire Bonzo the chimp to throw a dart before buying a car or choosing a mutual fund.

However, the leader of the chimpanzee study, Philip Tetlock of Wharton Business School, offers some hope. Tetlock last year released a book, Superforecasting: The Art and Science of Forecasting, (co-authored with Dan Gardner), which examines whether or not we can learn anything from our forecasting activities and become better at it.

Tetlock’s chimpanzee research encouraged him to look a little closer at the findings. While the average pundit did no better than the chimpanzee, he broke down the research a little by breaking down the forecasts and forecasters by accuracy – the forecasts came out of thousands of political, economic and other questions posed over a number of years – and seeing if there were any common traits between the most successful and least successful pundits.

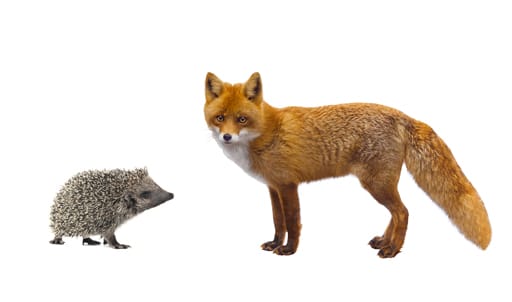

Foxes and hedgehogs

“The fox knows many things but the hedgehog knows one big thing.”

Tetlock found that the forecasters largely fell into two broad camps. On the one side were those who organised their outlooks on one or other Big Idea (which could be socialist or free market; or eternal optimism or pessimism, for example). On the other were those who were more pragmatic and keen to use as many analytical tools as possible, rather than looking at problems through a particular ideological or partisan lens (note that the two are two ends of a spectrum, many forecasters will fall in between them).

Tetlock called the former hedgehogs and the latter foxes, based on the line from a poem by ancient Greek writer Archilochus: “The fox knows many things but the hedgehog knows one big thing.”

The foxes beat the hedgehogs by a wide margin. Interestingly though, the hedgehogs tend to be the better-known pundits, despite their poor forecasting records.

Perhaps this says something about human nature. We prefer the the gurus and the pundits who “talk a good story” and have conviction around a few simple to understand ideas. It certainly makes for good television. The foxes, who preface their ideas with caveats and conditions, in short who recognise uncertainty, are less likely to draw news headlines or be studio guests. In the words of HL Mencken: “For every complex problem, there is an answer that is clear, simple … and wrong.”

This analysis of forecasters led to the launch of an ongoing research project, called the Good Judgement Programme, which invites people from all walks of life to participate in various forecasting exercises (see the end of the article for links on the programme).

The message behind Tetlock’s research and the book is not at all defeatist; he concludes that we can be better at making predictions. By engaging people from all walks of life in forecasting exercises over several years, he finds that some people are actually very good at it (and not necessarily the supposed experts). The book distils some of the findings and common characteristics of these “superforecasters” and reveals that it really is a skill that we can work on and get better at over time.

Good forecasters, those most resembling the foxes, he finds, are intelligent, but need not be super-intelligent. They are humble and open to questioning of their thinking by others. They set out their predictions in detail, including time horizons, and they then assign probabilities to outcomes.

This assigning of probabilities is crucial. Tetlock argues that some of the great military mistakes, like the failed Bay of Pigs invasion of Cuba in 1961, and the invasion of Iraq in 2003 that was wrongly predicated on the “certainty” that Saddam Hussein’s regime had weapons of mass destruction at their disposal, could have been avoided, if the intelligence teams had assigned probabilities to their conclusions upon which the military decisions were taken. More on this idea further below.

Good forecasters record their previous predictions and try to understand where and why they went wrong (or right). This helps to build a disciplined approach to predicting that minimises mistakes. The result may be a less forthright view of the future – and hence maybe a less appealing outcome for some – but rather something more nuanced to take into account the various risk factors.

They also draw on the aggregations of as many experts in a field as possible, recognising that good information can often be dispersed widely (this concept is explored in James Surowiecki’s famous book, The Wisdom of Crowds).

To conclude, Tetlock’s findings can be summarised in the “10 commandments” espoused in “Superforecasting”, which provide a good basis not just for forecasting better, but for how we assess the prognostications of the experts that we read or hear every day. They are a useful guide for all of us, even in our daily lives as we choose holiday accommodation or investments.

The 10 commandments for better forecasting

1) Triage: Focus on questions where your hard work is likely to pay off (what Tetlock and Gardner call triage – a medical term that assigns an order of priorities to patients or ailments based on their urgency). Don’t try to forecast too far in advance (eg don’t try to predict whether it will be raining in your hometown on New Year’s Day in 2030) or things where information is too patchy to draw meaningful conclusions.

2) Break it down: Break down complex and seemingly intractable problems into sub-problems. “Decompose the problem into its knowable and unknowable parts,” say the authors. “Flush ignorance into the open. Expose and examine your assumptions. Dare to be wrong by making your best guesses. Better to discover errors quickly than to hide them behind vague verbiage.”

3) Get an outside opinion: Balance the internal view of things with an outsider’s view. Compare your own estimates, or those of your colleagues, with those of people outside of your organisation or sphere. An outsider may lack the knowledge of the intricacies of a particular field, but is also less likely to be tied to insider’s ways (or biases) of assessing situations.

4) Clear out the noise: Constantly update your beliefs and assumptions based on new information, taking care to neither over- nor underreact to new evidence, but rather to strike a balance between the two. Through this process, we learn what new information is relevant and what is “noise”.

5) Watch out for cognitive bias: Look for clashing causal forces at work in any problem. Acknowledge the circumstances or forces that would make you change your view on any particular issue. Ask yourself: “If I strongly believe that X is so, what would make me believe Y instead?” This helps us overcome the cognitive biases that drive a lot of our forecasting.

6) Assign probabilities: Try to quantify the degree of uncertainty in a problem – at least as much as the problem requires. To use a poker analogy, a good player doesn’t vaguely say “I might lose this bet” but rather assigns proper probabilities – he knows the difference between a 60/40 bet and a 40/60 bet. This is an area where a lot of forecasting goes wrong.

Many tend to use vague terminology around the likelihood of a particular outcome, eg “a fair chance of X happening” (30% chance? 50% chance? 75% chance?); “I believe this product will be a success” (what time horizon – a year, two years, or more? And what metric will determine success – sales of X? Market share of Y%?).

By forcing forecasters to apply this sort of “granularity” one can avoid ambiguity and hopefully lead to better decision making. Would the US have invaded Iraq in 2003 if the experts had put the likelihood of the presence of weapons of mass destruction at 60%, rather than speaking as if they were 100% certain?

7) Balance is key: Strike a balance between decisiveness and thoughtful prudence. Work at recognising both over- and underconfidence. Rash decisions are bad, but so are dawdling and “analysis paralysis”.

8) Own your mistakes and your successes equally: Conduct post-mortems on both, because your incorrect forecast might have been well thought through but thwarted by something minor; by the same token, your correct forecasts may have been down to pure luck that hid some poor thinking. This process also feeds the process described in 6 above.

9) Master the art of teamwork: Good forecasting requires inputs from many perspectives but this can lead to conflict, especially if ego gets in the way. Equally, we shouldn’t let those with strong personalities drown out the perspectives of the rest, particularly the quiet but insightful team member.

10) Failure is an option: Forecasting is like learning to ride a bicycle – you can only get so far by reading a textbook. Make mistakes and learn from them. Again, this reinforces the processes described in 6, 8 and 9 above. As Irish playwright Samuel Beckett wrote: “Try again. Fail again. Fail better.”

About the author

Patrick Lawlor

Editor

Patrick writes and edits content for Investec Wealth & Investment, and Corporate and Institutional Banking, including editing the Daily View, Monthly View, and One Magazine - an online publication for Investec's Wealth clients. Patrick was a financial journalist for many years for publications such as Financial Mail, Finweek, and Business Report. He holds a BA and a PDM (Bus.Admin.) both from Wits University.

Receive Focus insights straight to your inbox