Get Focus insights straight to your inbox

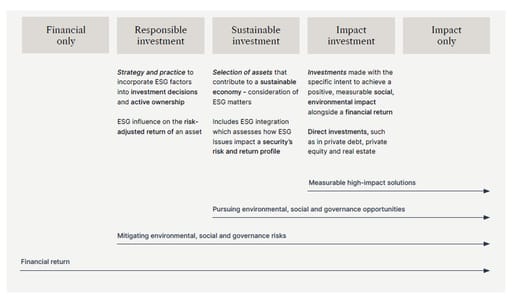

The spectrum of investing (Figure 1) can serve as a pathway to explore the evolution of investing and how responsible, sustainable and impact investing differ. It’s important for investors and philanthropists to understand these approaches to investing and how they align with their beliefs. This may be realised through the direct impact of funding provided to implementing organisations and/or indirectly through the investment strategies applied to capital.

Figure 1: The spectrum of investing

Source: Investec Wealth & Investment International, November 2022

A spectrum of investing

Figure 1 mirrors the evolution of a particular economic philosophy in relation to the role of business. Milton Friedman promoted a doctrine of shareholder primacy which held that decisions about social responsibility rest on the shoulders of the shareholders, not the executives, of a company. Under this view the aim is to maximise profitability or return while adhering to the rule of law and staying within the parameters set by government. This approach focuses on producing only financially targeted returns for investors (see the category to the left in Figure 1). Governments, however, have not been successful at establishing and maintaining parameters that enable a thriving and sustainable economic, environmental and social system for all. Lawmakers have been increasingly influenced by the powerful corporations which governments attempt to govern. As a result, negative externalities caused by inadequate policies and laws are being levied on society and the planet. Philanthropic efforts have played a pivotal role in minimising these negative impacts and have helped to hold society together as the systemic fractures have deepened. Such activities are often referred to as impact-only funding (see the category to the right in Figure 1).

Over the past decade, numerous organisations and initiatives have developed with the express purpose of measuring and reporting these negative costs of doing business, exposing the nature and extent of various undervalued company impacts. These include the Carbon Disclosure Project (CDP); the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI); the Value Reporting Foundation; and Harvard’s Impact-Weighted Accounts Project. The aim has been to quantify and, in some cases, recalculate a company’s profitability or valuation after taking its negative externalities or costs into account. These results then become material for investors to understand not only the financial valuation of the companies in which they are investing, but also to gain a more holistic recognition of these companies’ true value. This extends beyond financial considerations and seeks to price in their non-financial impacts too.

These initiatives help to promote responsible investing or environmental, social and governance (ESG) investing. Under a responsible-investing approach, asset owners and managers aim to determine whether companies are appropriately valued relative to their peers across sectors and geographies after considering material environmental, social and governance risk metrics. In some cases, this type of investing can be exclusionary – in other words, a particular company or sector may be excluded from the investment universe despite its valuation or profitability because it doesn’t align with the investor’s values or beliefs. They may even, through their activities, be contributing to the very environmental or societal problem that a particular charitable or philanthropic organisation was founded to resolve.

Moving beyond responsible investing, which focuses on how certain ESG risks may impact the valuation or future profitability of a company, sustainable investing focuses more on quantifying the positive or negative impacts that a particular company has on the environment or society through the products and services it provides or through its operations. This is a concept known as dual materiality which introduces impact into the spectrum of investing in the context of the impact that a company has on the world in which it operates. For example, it may consider issues of energy and water efficiency and/or regenerative, circular-economy solutions.

Impact investments, however, are made with the intention to generate positive measures of social and/or environmental impact alongside a financial return. In other words, the goal is additionality – a clear, measurable impact. There are different categories of impact investing dependent on the type of return being prioritised. Although many will be seeking a market-beating financial return, there will always be an objective to achieve certain outcomes under this form of investment. In some cases, the financial return received by the investor will reduce as impact targets are achieved and may even be a secondary focus if the aim is to provide capital to fund the implementation of an idea that should generate a positive impact. In this case, the only goal other than a return of the primary capital is for the project to be successful in terms of the environmental or societal impact it is trying to achieve.

At present, a key differential between impact investing and sustainable investing is liquidity. Sustainable investing typically focusses on listed asset classes providing sufficient liquidity for investors to redeem their capital quite quickly. Traditional “high” impact investments, however, are usually made into smaller unlisted businesses that are either raising private equity or private debt and have lower liquidity. These investments also typically lack transparency and, given the lower liquidity available, present additional risk.

Direct and indirect impact

While it is generally acknowledged that a listed corporate could have a positive impact through the products it sells or the way it operates – such as by being conscious of environmental impacts or through its adoption of favorable labour polices – it is not necessarily clear that any impact is being produced through the act of owning or buying shares in these businesses. For example, when such shares are purchased in the secondary market, no new capital is being raised through the purchase – the money paid goes to the seller of the shares, not the company itself. This is where the concept of “additionality” arises – in other words, the additional impacts that may accrue from one’s ownership of the shares rather than someone else’s.

One clear way of having an impact within the listed-company space is through stewardship and engagement activities. In particular, shareholders and those with savings invested in a particular company can wield significant influence through their corporate votes at annual meetings, driving change and holding management to account. In this respect, it is important to note that many investors take it for granted that their asset manager will vote on their behalf in line with their wishes, but this is not necessarily a given particularly in the case of passive investments, such as exchange-traded funds.

Shareholder activism provides the owner or manager of shares an important opportunity to have a real impact on the way a company is managed. While voting is the core of stewardship activities, “engagement” comprises a more active process. This may entail contacting the company in question either directly or collaboratively to try and spur meaningful institutional change. Such engagement can be as simple as asking for more ESG disclosure; or it could entail a request for specific information about changing policies or management teams. Engagement often requires escalation; and most companies that actively engage with their shareholders in this way will have a policy seeking to define the process, which may, in worst cases, lead to litigation or disinvestment from that company’s shares.

It is of utmost importance for investors to ensure that their risk requirements and financial priorities are aligned. In this context, responsible investing should be a minimum requirement for all investors, as well as a best practice in terms of asset managers’ fiduciary responsibilities. The question of achieving impact beyond this will then guide investors to find the investment approach that best aligns to their requirements. The opportunity in South Africa, where impact investing is a relatively small but rapidly evolving field of activity, is to solve for the liquidity and risk limitations posed by impact investing and perhaps create a unitised vehicle that provides investors with reasonable liquidity; lower risk through diversification; sufficient financial returns; and measurable impact. This is not an easy task, but it is not insurmountable. Humanity has shown that when people come together with a shared purpose, they can overcome the challenges they face.

As economic systems evolve to reflect their true purpose, which is to be of service to all stakeholders, so too does the spectrum of investment evolve, and at a pace that is faster than ever before. This means that the choices philanthropists make in seeking to achieve their desired impact are not limited only to funding implementing organisations, they have extended into being meaningful enablers of financing sustainable development and catalysts of lasting change. There is no greater time than now to be in a world that is finding new ways to unlock the power of capital to solve the most pressing challenges.

This article first appeared in the 2022 Annual Review of South African Philanthropy, published by the Independent Philanthropy Association South Africa.

Get Focus insights straight to your inbox

Disclaimer

Although information has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable, Investec Wealth & Investment International (Pty) Ltd or its affiliates and/or subsidiaries (collectively “W&I”) does not warrant its completeness or accuracy. Opinions and estimates represent W&I’s view at the time of going to print and are subject to change without notice. Investments in general and, derivatives, in particular, involve numerous risks, including, among others, market risk, counterparty default risk and liquidity risk. The information contained herein is for information purposes only and readers should not rely on such information as advice in relation to a specific issue without taking financial, banking, investment or other professional advice. W&I and/or its employees may hold a position in any securities or financial instruments mentioned herein. The information contained in this document does not constitute an offer or solicitation of investment, financial or banking services by W&I . W&I accepts no liability for any loss or damage of whatsoever nature including, but not limited to, loss of profits, goodwill or any type of financial or other pecuniary or direct or special indirect or consequential loss howsoever arising whether in negligence or for breach of contract or other duty as a result of use of the or reliance on the information contained in this document, whether authorised or not. W&I does not make representation that the information provided is appropriate for use in all jurisdictions or by all investors or other potential clients who are therefore responsible for compliance with their applicable local laws and regulations. This document may not be reproduced in whole or in part or copies circulated without the prior written consent of W&I.

Investec Wealth & Investment International (Pty) Ltd, registration number 1972/008905/07. A member of the JSE Equity, Equity Derivatives, Currency Derivatives, Bond Derivatives and Interest Rate Derivatives Markets. An authorised financial services provider, license number 15886. A registered credit provider, registration number NCRCP262.