Receive Focus insights straight to your inbox

Black tax is a term for financial support that a professional or entrepreneur of colour is obliged to provide to their family on a continuous basis outside of their own living expenses. Sometimes it is taken on subconsciously, as a kind of payback for sacrifices made by previous generations or family members.

In this first article in a series, I highlight the fundamental elements of black tax and unpack some of the issues underlying the concept, often drawing on my own experience. I will discuss what it means for young professionals trying to build their wealth as well as contribute to uplifting their families.

In a nutshell, black tax seeks to address the continued economic imbalances that can be traced back to apartheid, slavery, historical injustices, structural inequality and educational disparities. While others have described it as a form of investment – Ubuntu – it also has an incapacitating element. Whichever way it is framed, the giving is not cheerful.

Black tax seeks to address the continued economic imbalance that can be traced back to apartheid, slavery, historical injustices, structural inequality and educational disparities.

In black communities, the concept often arises from the cultivation of certain characteristics in a child from a tender age and phrases such as “remember where you are coming from” are repeated, instilling the idea that they are the umbrella in the family and a part of the success of the family rests in their hands.

While the term originated in South Africa, it is now used globally and the framework is common across the African continent and the US.

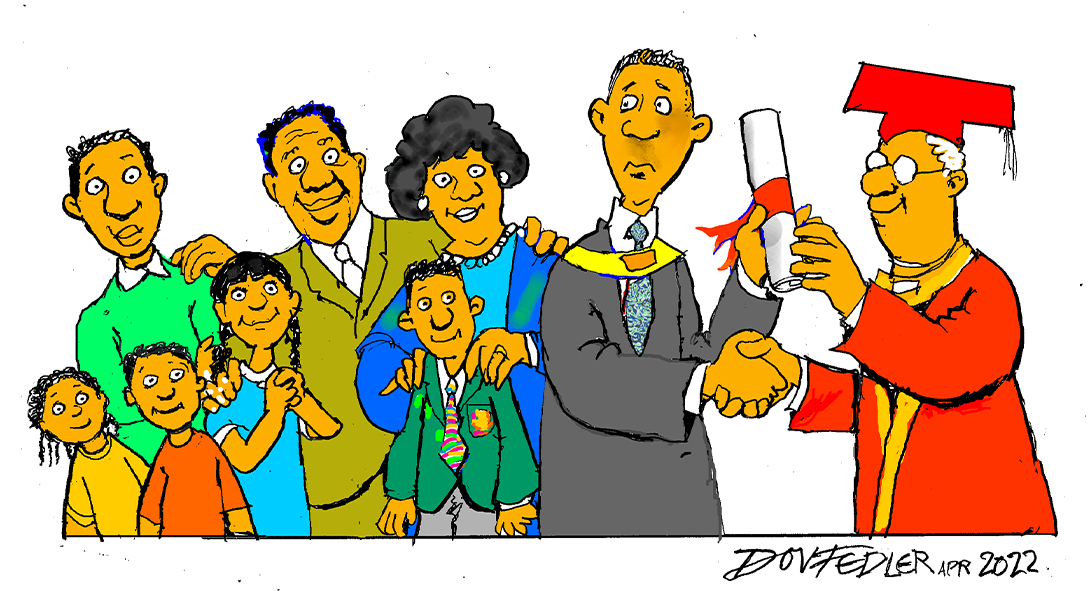

Often, the givers of these remittances are individuals with a higher education, a better paying job than the rest of the family or a small business – someone who has “made it”. It’s usually an aspiring individual who works hard to achieve good marks at school, gets a bursary to study at a prestigious university, puts their head down and graduates, and then becomes a chartered accountant, engineer, medical professional, investment professional, or embarks some other kind of professional career.

Their achievements bring hope of financial relief to the family, but in some instances the achievements become a burden for them. The assumption is that the individual now has the wherewithal to support even the extended family, and the “taxation” begins. And it’s not just the monthly expenses that are a burden – ad-hoc payments, such as contributing to a relative’s funeral expenses, can set you back as well.

Changing the course of our destiny

In my own case, I grew up in an intimate family of seven – my mother, older brother, two older sisters, younger brother and cousin. My mother worked hard to give us a relatively comfortable childhood, all on a nurse’s pay cheque. As such, I have happy childhood memories of feasting and monthly family outings like going to the zoo, and it often felt like we were living like royalty because we did not know better. My mother prioritised education and pushed us all to go to university.

When my older brother went to university huge changes were made and we had to sell assets and cut out family outings. Going to the beach became an annual occasion. Two years later, belts were tightened further in order to send my older sister to university. The only times we would have treats were on payday and our lunch boxes started to look similar to the school’s feeding scheme food. We collectively made sacrifices to carry my siblings. I started a small business in primary school selling sweets and biscuits to pay for stationery. We did not mind; we counted the years each were left with till they graduated because the hope was that once one sibling had graduated, they would immediately help pay for the next one’s university fees. It was a recurring system of sacrifice to pull each other up and change the course of our destiny.

While at university I juggled two and half jobs, and when I graduated I understood that I had limited time to take up the first available job so I could send money back home. However, I was not prepared for the unspoken challenges of a black female entering the wealth management business. I had to grapple with the harsh reality of my gender, race, background, ranking in society, and the impression of my colleagues and clients. Yet, I had to start sending money, even as I had to build an acceptable image (I needed new clothes, etc). The system I grew up in encouraged a universal law of sacrifice.

My brother and sisters before me had no choice but to contribute to helping reverse the poverty caused by the sacrifices made by my family to put them through university. As the second last born, by the time I graduated my younger brother was already at university and my mother only had my brother and herself to support. In my case, there was an expectation to contribute, even though the need to help fund others’ educational needs was no longer there. It was a kind of dividend on the investment my mother had made through her hard work and sacrifices. She wanted the extended family, friends and community to see the payoff of her investment in us.

Is it an investment or a burden?

While many might see black tax as a burden on individuals, it also has a pivotal socio-economic role to play. It lifts families out of poverty, uplifts communities, and builds generational wealth.

If my family had not subscribed to this system of sacrifice, if my older brother and sister had not contributed once they had graduated, we would have never gone to university and I would have never become an investment professional. My life and that of my siblings would have turned out very differently. But we defied the odds, collectively, and we broke the cycle of generational poverty, of scraping by, thus allowing us to concentrate on the long-term goal. Today I have the generational wealth to start my adult life.

Hence, when people speak of generational wealth, in this context, it has a personal meaning for me. For people like me, we had no real safety net other than family. There was no inheritance coming.

At the same time, the unintended consequences cannot be ignored. A young professional of colour is already starting on the back foot when it comes to creating wealth. There was never any generational wealth to provide a nest egg or a cushion to allow risk-taking, such as becoming an entrepreneur. In addition, the burden of having to share your salary diminishes your capacity to invest, save towards retirement, or build capital to start a business.

This is seen in other parts of the world as well. A report by the Institute of Policy Studies revealed that 37% of black families in the US (where black tax is also common) have debts that are equal to or greater than their assets.

A report by the Institute of Policy Studies revealed that 37% of black families in the US (where black tax is also common) have debts that are equal to or greater than their assets.

The system embedded in Africa (and the US) is failing black people

In contrast with Western societies, the African system encourages black tax, or at least creates the conditions where families have no other choice. The black middle-class is obliged to take care of the poor and the culture of taking care of each other is in the fibre of black communities. It is second nature, and the essence of the concept of Ubuntu.

In many Western societies, where the middle and upperclasses form a larger proportion of the population, the social system takes off the burden from the shoulders of its citizens. If you are rich and your brother is poor, he does not have to come to you – the government will make sure his necessities are met, including free education and healthcare.

While the US has a broad social system relative to African countries, people of colour are systematically disadvantaged when it comes to building wealth. The practice of “redlining” certain areas, under which the government does not guarantee loans for black Americans trying to purchase homes, is just one example.

Governments in many African countries fail their people by not using their taxes efficiently or appropriately to provide for people’s basic needs. Black tax then becomes a double tax on black professionals because they end up paying for the services that are supposedly provided for by government from the taxes they pay.

The good news is that some governments are starting to recognise the role these remittances play and offer some form of subsidy. The Central Bank of Nigeria in March last year introduced a “Naira 4 Dollar Scheme” which allows the sender and recipient to earn ₦5 on every US dollar remitted from abroad by Nigerian expatriates, to encourage an increase in the inflow of remittances (and foreign currencies). These and other initiatives may well be the blueprint for future policies.

Ancient law of sacrifice

Black tax, or at least the philosophy behind it, is part of the backbone of communities of colour. Through this ancient law of sacrifice, the African child can change the course of their destiny.

However, the deck is often heavily stacked against and the weight of it all can feel overwhelming — no matter your net worth, or how much you’ve achieved. For a black female like me, systemic inequities and generations of poverty can make it seem like whatever you’ve done is never enough, especially when you know you will have to support your family.

Keep an eye out for our upcoming articles as we explore this important element of our economy and attempt to educate, offer optimal solutions, and lobby for stakeholders to find creative ways to lessen the burden while uplifting families and communities.