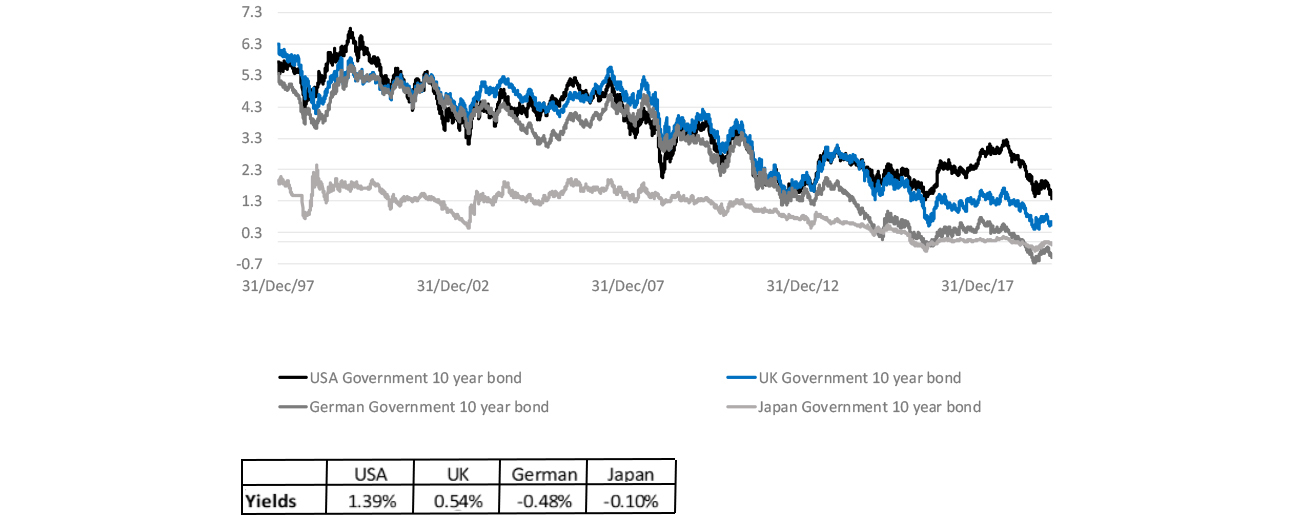

If we are to take the signals from global bond markets seriously, then savers should expect a decade or more of very low returns. The decline in bond yields due to mature in 10 years or more has accelerated dramatically during and after the global financial crisis (GFC):

Developed Market Government Bond yields

Source: Bloomberg and Investec Wealth & Investment

The expectations of low inflation is part of the explanation for these lower yields. But it is more than lower expected inflation at work. Yields on inflation-protected securities – those that add realised inflation to a semi-annual payment – have declined to rates below zero. Before the GFC, the US offered savers up to a risk-free 3% return per year for 10 years, after inflation. The equivalent real yield today is a negative one of (-0.11%).

Real yields on US 10-year inflation-linked bonds (TIPS)

Source: Bloomberg and Investec Wealth & Investment

These low risk-free rates also mean that firms investing the capital of their shareholders have very low investment hurdles to clear, in order to justify their investment decisions. A 6% internal rate of return would be enough to satisfy the average shareholder given the competition from the fixed income market. You might also expected equity market returns to gravitate to these lower levels.

Another way to describe these capital market realities is to note that the rate at which the value of pension and retirement plans compounds is expected to be at a much slower one than in the recent past. Savers will need to save significantly more of their incomes to realise the same post-retirement benefits.

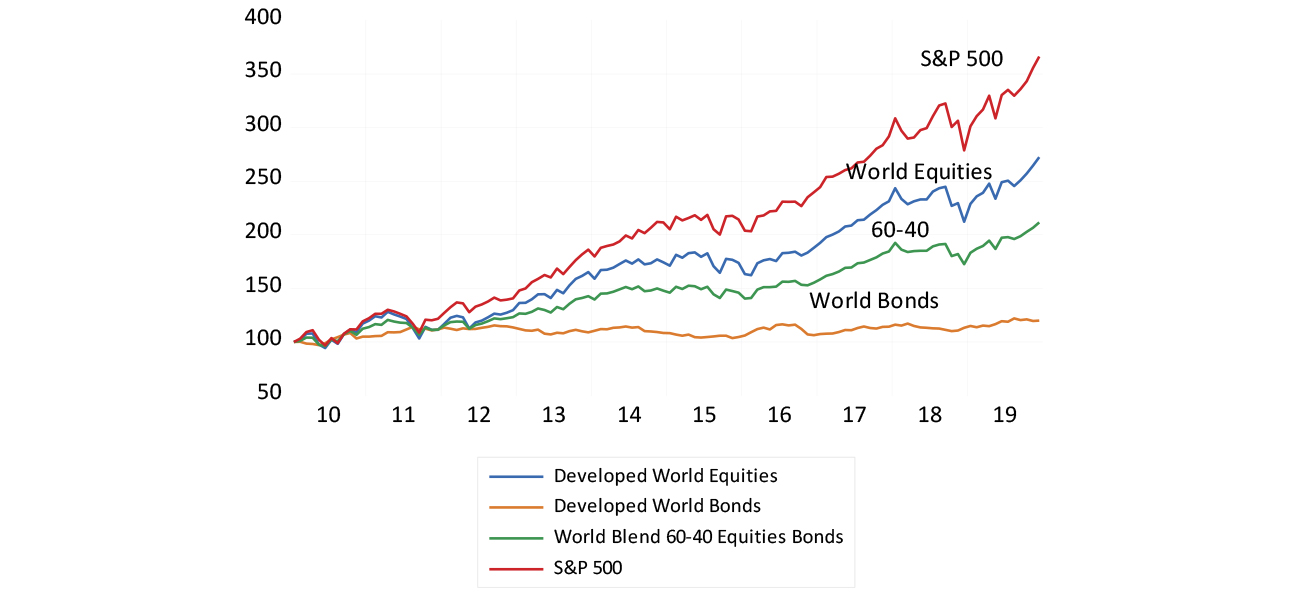

The past decade has been particularly good for global pension funds. In the 10 years after 2010, the global equity index returned 10.5% a year on average while a 60/40 blend of global equities and global bonds returned an average 6.4%, with less risk. US equities would have served investors even better, realising average returns of 13.4%, well ahead of US inflation of 1.8% over the period.

Total portfolio returns 2010-2019 (January 2010 =100)

Source: Bloomberg and Investec Wealth & Investment

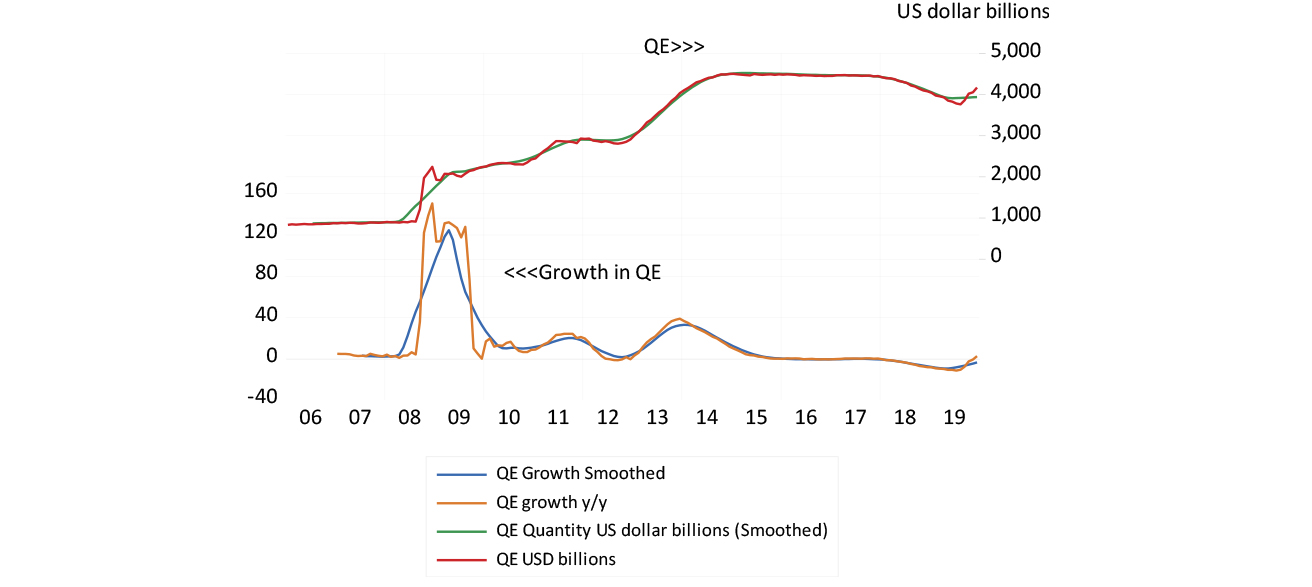

Why then has global capital become so abundant and cheap over recent years? Many would think that quantitative easing (QE), the creation of money on a vast scale by the global central bankers, has driven up asset prices and depressed expected returns. More thanUS$3 trillion has been added to the stock of cash since the GFC.

Global money creation

Source: Bloomberg and Investec Wealth & Investment

But almost all of this cash has been added to the cash reserves of banks and not exchanged for financial securities or used to supply credit to businesses that could have stimulated extra spending. Bank credit growth has remained muted in the US and even more muted in Europe and Japan.

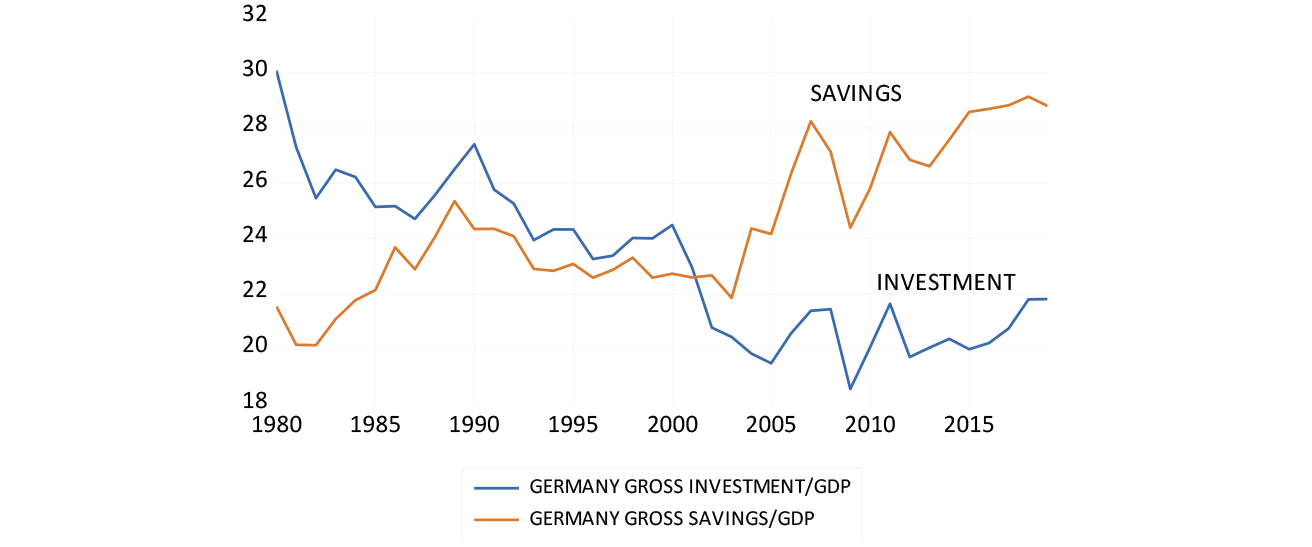

The supply of global savings has in fact held up rather better than the demand for it, helped by an extraordinary increase in the gross savings-to-GDP ratio in Germany. These savings have increased from about 22% of GDP in 2000 to 30% of GDP in 2018, while the investment ratio has remained at around 22% of GDP. Government budget surpluses have contributed to this surplus of savings in Germany.

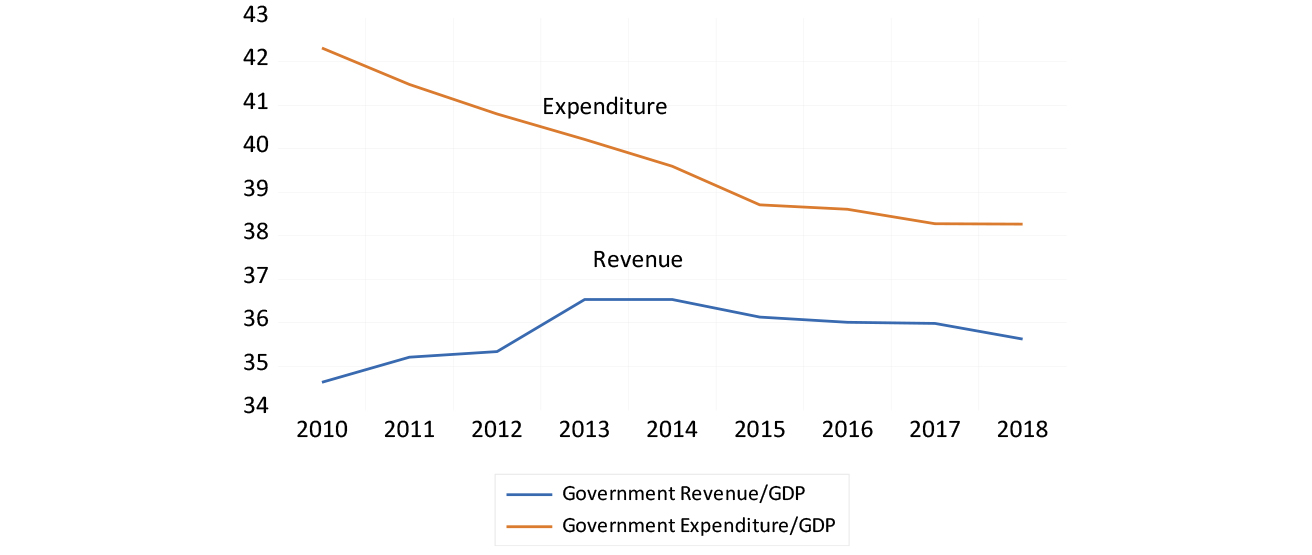

For advanced economies, the share of government expenditure to GDP has fallen from 42% in 2010 to 38% in 2018, while the share of revenue has remained stable at about 35% of GDP. This could be described as global fiscal austerity, in the wake of the confidence-sapping GFC.

Germany – Ratio of gross savings and investment to GDP

Source: IMF World Economic Outlook database and Investec Wealth & Investment

Advanced economies – Ratio of government expenditure and revenue to GDP

Source: IMF World Economic Outlook database and Investec Wealth & Investment

What might be depressing the demand for capital is the changing nature of business investment. The production of goods and services (which command a growing share of GDP), may well require less capital today than in previous years. Investment in research and development is often not counted as capital at all. At the same time, intangible capital is not easily leveraged.

Lower interest rates have their causes, but they also have their effects. They are likely to encourage more spending – by governments and firms and households. US President Donald Trump does not practise fiscal austerity. UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson also appears eager to spend and borrow more.

It would be surprising if firms and other governments did not respond to the incentive to borrow and spend more and compete more actively for capital. Permanently low interest rates and returns and low inflation may be expected – but they are not inevitable.

About the author

Prof. Brian Kantor

Economist

Brian Kantor is a member of Investec's Global Investment Strategy Group. He was Head of Strategy at Investec Securities SA 2001-2008 and until recently, Head of Investment Strategy at Investec Wealth & Investment South Africa. Brian is Professor Emeritus of Economics at the University of Cape Town. He holds a B.Com and a B.A. (Hons), both from UCT.

Get Focus insights straight to your inbox