Receive Focus insights straight to your inbox

As with many things in life, where the potential rewards are the greatest, so are the risks. Some of South Africa’s most successful businesses can be classified as family businesses: Pick n Pay, Nando’s, Pam Golding, De Beers. There’s plenty of research that shows1 that family businesses:

- Are more profitable in the long run.

- Are less likely to retrench staff even during economic downturns.

- Are more likely to become involved in philanthropic initiatives in the communities in which they operate.

- Have a more long-term strategic outlook, given the goal of creating a cross-generational legacy.

- Are less likely to finance by debt and tend to be financially conservative.

Disproportionate economic impact

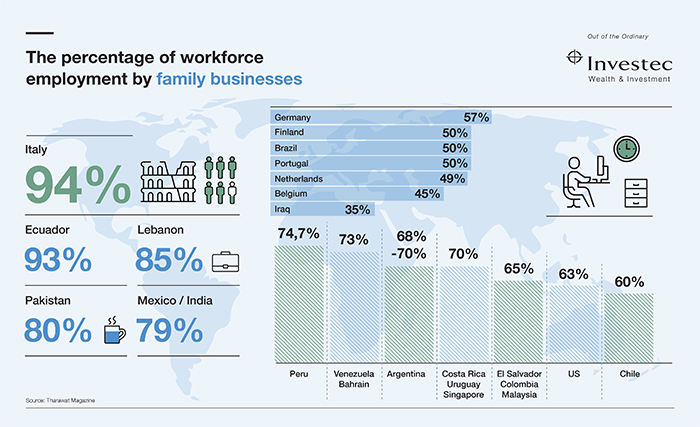

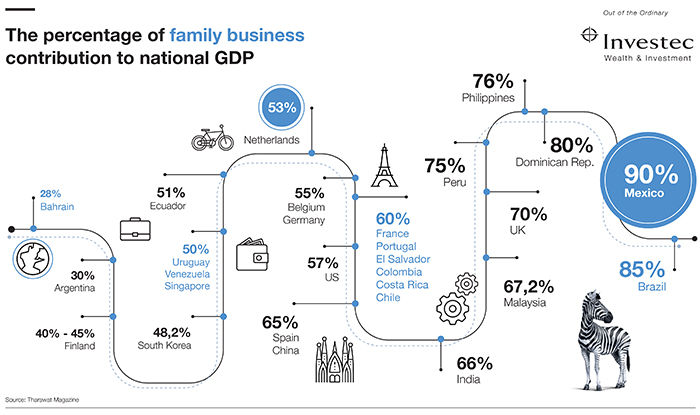

These qualities may go some way to account for the apparently disproportionate impact that family businesses have on the market economy. A study by Tharawat Magazine2 revealed some startling statistics, about the role of family-owned businesses, as we show below:

The percentage of workforce employment by family businesses

The percentage of family business contribution to national GDP

However, on the risk side of the pendulum, we also know that the chance of a family-owned business surviving the transition from the first to the second generation are regarded as around 30%; and the chance of surviving from the second generation to the third seems to be around 10%. As the saying goes, it’s often a case of going from clogs to clogs in three generations.

Unique risks

During the first generation phase of a family business, ownership and management vest in one person, the founder. By the time the business transitions to the second generation, various ownership and management structures emerge. It is at this stage that one begins to see a divergence in who owns shares and who manages the business. Once you get to the transition to the third generation (sometimes referred to as a ‘cousin-consortium’), the divergence between ownership and management will be even wider, and will often involve multiple non family members at both levels.

There is a higher potential for internal conflict where business and personal lives are not appropriately separated. Family values such as equal treatment, such as between siblings, may conflict with business values where not all siblings are as involved in the business or one outperforms the others. These dynamics create fertile ground for conflict. Such conflict stifles employees’ ability to develop and achieve common business objectives and will negatively impact the work environment for both family and non-family employees.

Once non-family members become embedded in the management and ownership structure, another potential area of conflict arises, namely between outside shareholders (family members who do not work in the business) and inside shareholders (family and non-family members who do work in the business). Conflicting views and priorities typically emerge over issues such as reinvesting profits as opposed to paying dividends, remuneration, transparency, perks for those working in the business and the long-term strategic direction of the business.

The Gucci Family provide us with an interesting case study. It started out as a textbook example of first to second generation success. When the founding patriarch, Guccio Gucci, died in 1953, the business was left to Aldo, the oldest of the three sons. Aldo quickly expanded the business to the major markets outside of Italy. This soon made Gucci an international name in fashion. However, without a clear direction for the future of the company, problems arose when his son Paolo wanted to launch a new fashion line. When his father and uncle shot down the idea, he launched it behind their backs. As a result, he was fired and exiled from the family business.

Paolo sought revenge by exposing Aldo’s tax issues, which saw him eventually serve a year in prison for tax evasion. Eventually, Paolo and his cousin Maurizio took over the business. However they still lacked clear direction and they found themselves with a negative net worth of some $17.3 million and more than $40 million in personal debt. They were finally forced out of the company by Investcorp3.

Sunny Tan, the youngest son of the Tan family patriarch, Tan Siu Lin, and CFO of Luen Thai Holdings Ltd, has spoken openly about the fight for unity, living family values and the business of expansion.

By contrast, the Luen Thai Group is an example of a family business that has successfully tackled the inevitable challenges. Together, this family controls a multi-billion dollar global conglomerate incorporating businesses in the shipping, airline cargo, hospitality and apparel-manufacturing sectors, among others. Sunny Tan, the youngest son of the Tan family patriarch, Tan Siu Lin, and CFO of Luen Thai Holdings Ltd, has spoken openly about the fight for unity, living family values and the business of expansion. He explained that his father’s guiding principles for the family were: honesty, integrity and respect for the elders. However, as the children grew older and became part of the business, they realised that implementing these values across an organisation was a different matter. They hired experts to guide them through a crucial turning point. At an offsite workshop, the second generation siblings addressed the fundamental questions: What were their dreams and ambitions? Did we want to stay together?

The result, as he explained: “Despite our differences, we knew we were stronger in union, that we all learn from each other. But if we wanted to be together we had to address our shortcomings. Accepting that we are all different and that we have to always find ways to work things out between us, was key.”

They realised that they needed corporate governance and family governance. They established a family office, hired external staff to maintain impartialness and implemented policies that were geared towards the good of the whole family and not someone’s personal preference. They also have family committees in place and try to develop various aspects of the family business by sharing their time in as structured way.

Strategy for success

The three areas that successful family businesses navigate well are business governance, ownership governance and family governance.

On a business level, successful family businesses ensure that:

a) There are systems in place to enable the founder or the family members to obtain objective advice from non-family member directors or formally appointed non-family member trusted advisers (the ‘consigliere’, in ‘The Godfather’ parlance);

b) The business is professionalised (by creating a formal work/professional business culture distinct from the informal family culture); and

c) Full buy-in is obtained in the creation of a clear succession plan for management and leadership positions in the business. In many cases, the shares in the business are held by family trusts and these boards as well as the company boards of directors should include independent trustees and / or directors who provide objective business advice at these levels of business governance.

Successful family businesses pay adequate attention to the health of the family’s emotional system.

On an ownership level, trusts are often used to hold the shares in a family company or group of companies. Trusts provide protection in the event of risk events such as litigation, divorce or insolvency. In addition, trust deeds supported by a detailed letter of wishes typically provide detailed rules for the transfer of beneficial ownership between generations. The detail needed here covers rules governing how the voting rights on the shares are to be exercised, the requirements for quorums, the required majority for different types of decisions, and what to do in the event of a deadlock; representation of each branch of the family on various committees or board, or otherwise explaining the rules dealing with membership and succession of such committees and trust and company boards. Another tool frequently used is a shareholders’ agreement or liquidity plan allowing a mechanism for family members who are not emotionally committed to the business to realise their interests.

Thirdly, successful family businesses pay adequate attention to the health of the family’s emotional system. The key mechanism used to achieve and maintain this objective is the ‘family meeting’ (or in larger families, the ‘family council’). Formal family meetings create a framework for the discussion of family issues so that trust and communication between family members can be continuously fostered. These meetings enable shared family values to be re-articulated and embedded into the everyday life of the family and the business. They provide a space for the family to plan for challenges or transitions the family will face.

Tool for success

A key tool for success is a timely and carefully negotiated family constitution. The process by which the document is created and the detail it covers are crucial. The process creates a unique and facilitated opportunity for a family to engage in a deep and meaningful reflection about its history, values, principles and goals. The conversation should be aimed at creating alignment between family members on these fundamental issues and motivators. The buy-in achieved and agreements reached in a successful process shape the decisions taken and documented around the business, ownership and family governance mechanisms discussed above. And these mechanisms, in turn, serve to maintain the alignment achieved between family members during day to day, cross generational and unforeseen challenges that the business and the family will face.

1 ‘Economic Impact of Family Businesses – A Compilation of Facts', Tharawat Magazine, 1 June 2016

2 Issue 22, 2014

3 ‘When Succession Goes Awry – Four Famous Examples of Failure’, By Tony Sekulich -2018-10-24

4 'The Tan Family and the Strength of Unity' - Tharawat Magazine, Issue 28, 2015

Investec Tax & Fiduciary helps Investec clients, that meet the discretionary minimum investment requirements, to navigate the complexities of local and international wealth structuring.

Trust us to manage your wealth today