Receive Focus insights straight to your inbox

Perhaps the biggest headlines to emerge from the recent G7 gathering of government leaders was the agreement to back a global minimum tax of 15% for the world’s largest companies. The countries also agreed on the principle of broadening taxing rights to jurisdictions where companies do sales, not just where companies have offices.

The proposals are aimed at a group of large, highly profitable multinationals – still to be defined, but likely to include the world’s tech giants – whereby those countries in which the multinationals have at least 20% of their profits, can tax above a 10% margin.

The proposals still face a number of hurdles before they become reality. First, they need to be approved by a broader group of countries, notably the G20 (which includes the likes of India and China). Resistance may also come from European Union countries, such as Ireland, which has a 12.5% corporate tax rate.

According to The Economist magazine, the wealthy G7 countries would reap over 60% of the revenue gains under a minimum tax of 15%.

Developing countries are also likely to show some resistance to the proposals. According to The Economist magazine, the wealthy G7 countries (the US, Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan and the UK, representing 40% of global GDP), would reap over 60% of the revenue gains under a minimum tax of 15%.

Even if the global tax minimum gets support from the broader group of 20 nations, it still needs to get 139 countries in the OECD’s Inclusive Framework to sign. The proposal is likely to face resistance with developing countries, as the global tax minimum operates to limit a state’s ability to make tax policy as it deems fit, essentially limiting its right to sovereignty in the name of updating a global taxing framework.

A global tax rate will inevitably redefine what is an acceptable tax base and what is an acceptable tax rate. As such, it does not necessarily attempt to harmonise taxes, but instead, it sets boundaries within which a country is expected to operate. If the global tax minimum were to pass, it would essentially undermine investment incentives of many tax havens and developing countries that offer lower tax rates to attract tech companies, call centres and the like. Furthermore, countries such as the Netherlands and the UK would also be affected as they both offer low tax rates on income from the development of intellectual property. One might even argue that the global minimum tax will limit appropriate tax competition between nations and that this will have massive ramifications for smaller nations who may now no longer be able to compete with larger nations that have inherent economic advantages.

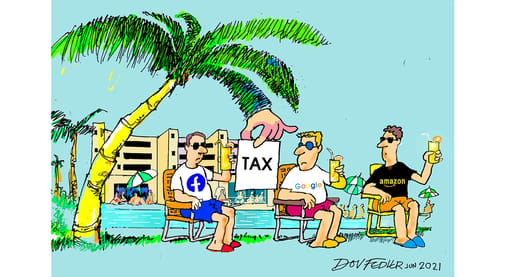

It is worth noting that the G7 proposal does not make mention of digital services taxes. There is speculation that if the corporate tax minimum becomes a reality, the digital services taxes will be scrapped, meaning that big tech companies such as Amazon, Google and Facebook would benefit immensely, since digital services taxes are levied on their gross revenue rather than profits.

All of the above suggest that rolling out a new global corporate tax regime will take time and that the end result may look rather different. Nonetheless, it shows a clear turning point in the approach by the world’s governments to tax. For decades, global legislation has favoured multinationals looking to minimise their tax by being able to have bases in different, low-tax geographies.

Critics point out that there has been little alignment between economic activity and tax paid in any one country. Many argue that the effective implementation of a global tax minimum requires an independent international tax body to oversee the implementation of a tax minimum, ensure compliance and to act as a tax collector. Perhaps it’s time we considered building an international tax court so that we may increase international cooperation amongst states.

Against this background, it should be noted that governments around the world embarked on ambitious stimulus programmes during the pandemic, aimed at minimising the economic impact on their citizens and to address long-standing issues such as infrastructure, healthcare and inequality. They are therefore likely to target tax optimisation over tax competition in future.

What are the implications for high net worth individuals?

While the G7 summit did not directly address taxation of individuals, the world’s wealthy are likely to be in the cross hairs of tax regulators in the years to come. Most countries have units dedicated to increasing the efficiency of tax collections among high net worth individuals (HNWIs). Examples include HNWI units in the UK and Australia, and US Internal Revenue Service’s wealth squad.

Earlier this year, SARS launched its first High Wealth Individual Taxpayers Unit (the Unit), which aims to improve compliance among wealthy taxpayers. The Unit will enable SARS to conduct more lifestyle audits and use alternative sources of information to investigate the discrepancies between money spent by HNWIs and the tax income declared, with the goal of ultimately increasing collections from this segment of the tax base. SARS has promised that the Unit’s service offering will be informed by global best practices. We will watch these developments, both locally and globally, with interest.

Trust us to manage your wealth today