Inflation, and in particular food and petrol/energy inflation has come under sharp focus in recent times. In this note, we explore some of the salient themes over the last year and share our thoughts on the current inflation trajectory, particularly taking into account some of the identified upside risks.

At the outset, we should draw attention to an article by Luke Fraser that appeared in BusinessTech a few weeks ago, South African food producers need to brace for drought: economist, quoting leading agricultural economist Wandile Sihlobo’s warning of dry conditions prevailing from October, as the country enters into the El Niño weather pattern. This was a worrying headline considering the consensus that we are moving towards the tail-end of elevated food inflation (if we have not already passed it), with expectations of an imminent moderation.

Local agricultural production has been excellent and local and global agricultural demand has been robust, but changing weather patterns could pose a risk next year. The demand-supply mismatch is expected to push up food prices should drought conditions take hold and affect livestock and agricultural production.

The events of 2022 are still fresh in the memory. The residual impact of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, and global supply chain challenges, among others, continue to filter through the system. These two events had significant implications for global inflation, which remains stubbornly high. Just recently, the US reported year-on-year inflation for February at 6%. US inflation is moving in the right direction but is still uncomfortably high relative to the central bank target of 2%. China is the only major economy where inflation is below the central bank target. Meanwhile, emerging markets are expected to tame inflation to within their central banks’ targets this year, while developed markets should follow suit next year.

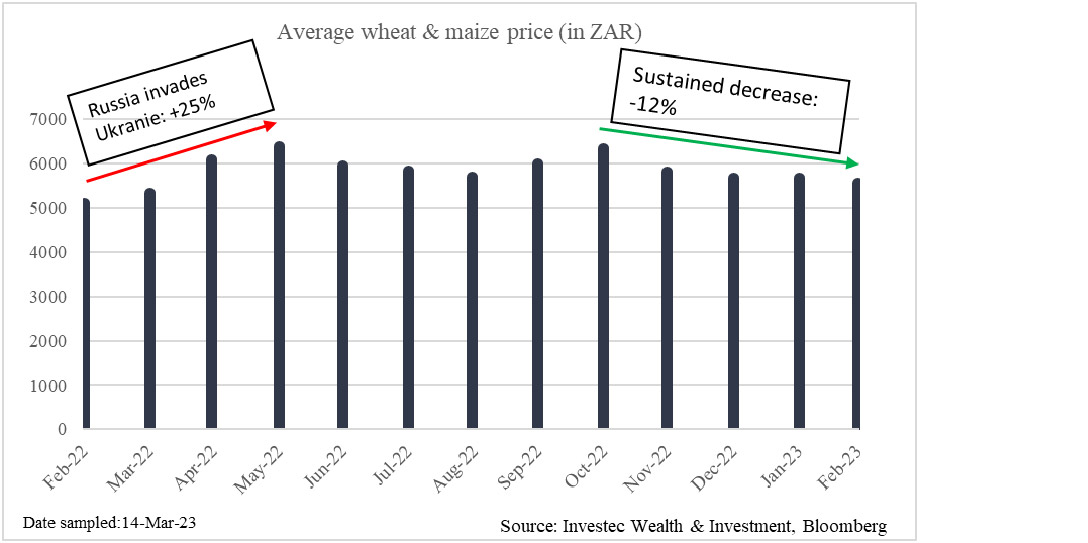

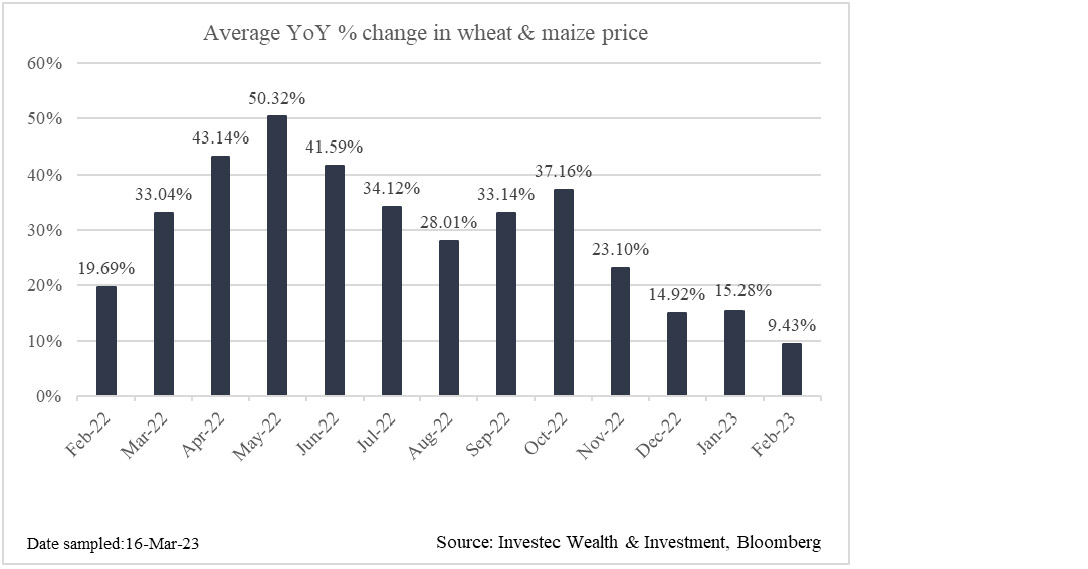

In South Africa’s case, the first important point to make is that the average SAFEX wheat and maize pricing has seen a relatively sustained moderation over the last five or so months. This should be a net positive for the directionality of food inflation in South Africa. Prices at the end of February for maize and wheat were up 9.43% year-on-year. Charts 1 and 2 below show just how pronounced the moderation in price rises has been, since peaking at +50.32% year-on-year in May.

Chart 1: Average SAFEX wheat and maize price

Chart 2: Average YoY % change in SAFEX wheat and maize price

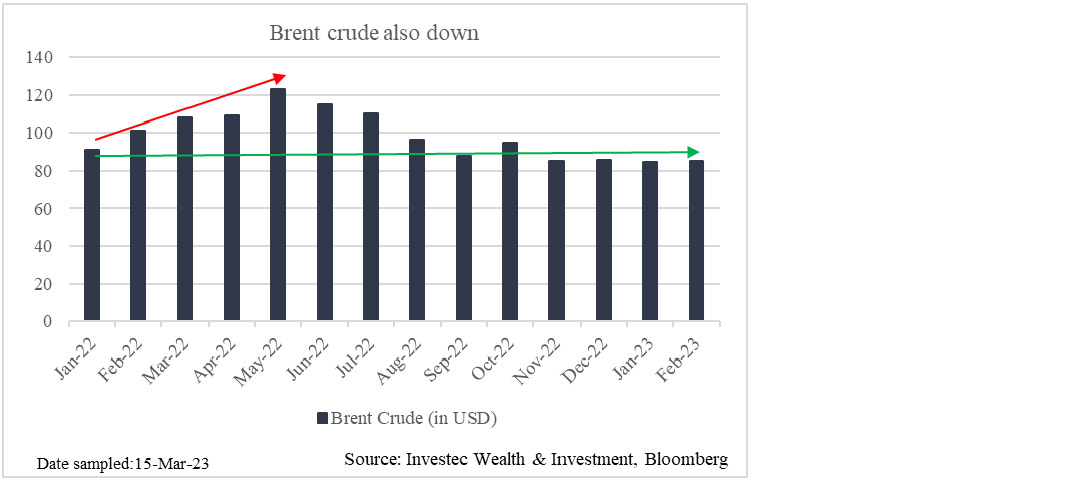

The increases in food pricing coincided with increases in the price of Brent crude. The spillover effects of the war in Ukraine drove prices higher, the result of Europe’s reliance on Russian oil and gas, as well as the global supply chain glut. But, as has been the case for agricultural commodities, what we have seen of late is a sustained decline in the price of brent crude (see chart 3 below). The price of Brent crude is now below what it was in January 2022, just before the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

Chart 3: Brent crude price

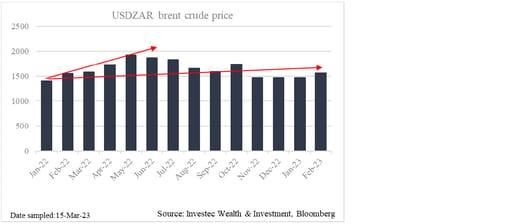

But despite the moderation in agricultural commodities and oil prices, there are several risks to the South African food inflation trajectory. The first of these is the weaker rand/US dollar exchange rate. The weaker currency has offset the benefits of lower-priced oil (see chart 4 below) and marginal benefits of lower agricultural prices. Petrol pricing in South Africa would be materially lower had the rand been stronger against the dollar, which would have been a net positive for South Africa’s inflation dynamics. The price of Brent crude in rands is not yet below the levels seen in January and February 2022.

Chart 4: Brent crude price in rands

Another factor is the cost of fertiliser. South Africa imports around 80% of its NPK (nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium) fertiliser. Fertiliser is one of the key inputs for agricultural production and this is another way in which the weakness in the rand/dollar exchange rate filters through the agricultural goods value chain and poses a risk to the inflation outlook.

Then there are the other ongoing challenges, such as Eskom and its impact on the agricultural sector or the wage-setting impact of higher inflation, which becomes a labour issue.

But all hope is not lost. According to our Investec Wealth & Investment food inflation model, the declines in the rand/dollar-adjusted pricing of wheat and maize suggest that food inflation should be somewhere between -2% and +3% relative to core inflation by year-end. Following the January 2023 Monetary Policy Committee meeting, the Reserve Bank expects core inflation to be 4.6% in the third quarter of this year, which suggests food inflation should be somewhere between 3% and 8% by then.

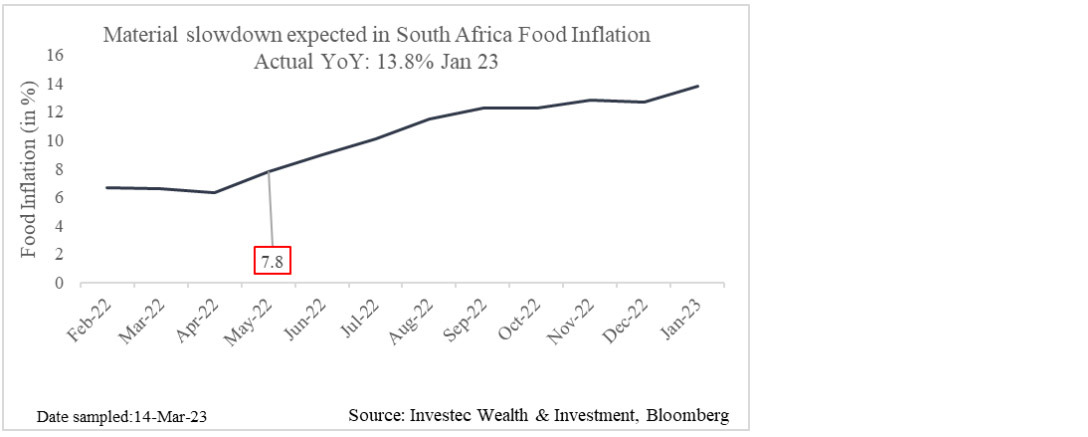

Based on the model, we would expect a material deceleration in food inflation. It’s worth noting that the last time food inflation was below 8% was in May last year (see chart 5 below).

Chart 5: South Africa Food CPI over the last year

But we must assess our base trajectory in the context of the prevailing risks in South Africa. A weak exchange rate, continued rolling blackouts, the sensitivity of oil prices to dynamics beyond our control, labour issues, and a potential El Niño-induced drought, among others, are threats to bringing food inflation under control. This could manifest itself in the form of higher headline inflation, as a combination of these factors, plus the NERSA tariff increase, education and medical aid inflation also come into play over the coming months. A wide range of retailers, in recent financial results, have already put into perspective the devasting effects of rolling blackouts.

These are material risks, with wide-ranging implications, including interest rates and the relative cost of living for South Africans.

You can also sign up to the Investec Focus newsletter for our latest insights