Despite the stereotypical portrait – Kalashnikov carrying, vodka drinking, oil drilling – Russians are also adroit farmers.

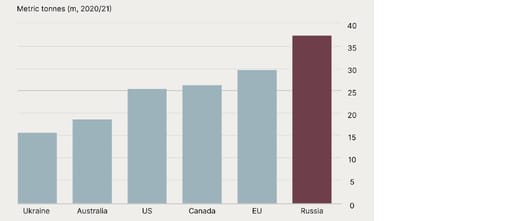

They till vast tracts of land, made increasingly arable by warmer temperatures, to produce bountiful bushels of wheat, maize and sunflowers; they are the world’s largest exporter of the former, with Ukraine not far behind.

Russia leads in global wheat exports

Source: USDA, Financial Times

South Africa is an offtaker of Slavic wheat surplus, accounting for 10-30% of our imports over the last three years. That begs an important question.

Wartime farming

What impact will the war have on Russian and Ukrainian agricultural output? It’s anything but clear-cut given the fluid nature of the conflict, but here are some things to think about:

Good news

- The Slavic wheat crop is already in the ground, with harvest season beginning in July/August

- Farmers should already have what they need to plant the maize and sunflower crops in April

- No trade embargo on Russian grains has yet been implemented

Bad news

- Financing for Russian and Ukrainian farmers will become scarce and expensive

- Shipping fleets to stay away from ports in Ukraine (safety risk) and Russia (reputational risk)

- Sanctioned Russian banks won’t be able to grease the wheels of their import/export businesses

In summary, farmers on both sides may reap a decent wheat harvest mid-way through 2022, but it might never ride the shipping lanes of the Black Sea and beyond. The longer-term outlook is perhaps grimmer, with no guarantee that farmers will have the funding nor incentive to plant their 2023 wheat, maize or sunflower crops.

Beyond food

The price per bushel of wheat is up circa 50% in sympathy of the uncertainty outlined above. Unfortunately, in the context of global food inflation, wheat is but one casualty of war.

Breath-taking fuel prices are going to increase the cost of anything that needs to be transported.

Sanctions on Russian aluminium producers (40% of global supply) will make packaging more expensive.

Fertiliser prices are likely to rise as Russia’s substantial natural gas and potash supplies become stranded.

The latter point is particularly concerning for the medium- to long-term cost of food production. Brazil, for example, relies on Russia for around 25% of their fertiliser imports needed to grow their world-feeding coffee, soybean and sugar crops.

War’s inflationary harvest

South Africa only produces about 50% of the wheat it needs and so must import the shortfall. But we do export maize in the region of 1 million to 2,5 million metric tonnes per year.

With the Slavic conflict taking on a siege-like pallor, now would be an opportune time for investment into additional maize production and the export infrastructure needed to fill and potentially capture a global supply gap in the yellow staple.

Our PGM producers are probably thinking the same way now that Russian supply is offline.

For local FMCG stakeholders looking to hedge against or take advantage of rising commodity prices caused by the war, we recommend exploring the following options:

- Buy commodity ETFs

- Increase raw material stock levels

- Use futures to buy forward

We listed a Russian invasion as a threat to SA food inflation in our last communication – we wish we’d been wrong.