Get Focus insights straight to your inbox

Among the many participants in the eighth edition of the Investec Cape Town Art Fair (ICTAF) are three young Johannesburg photographers: Sibusiso Bheka, Thembinkosi Hlatshwayo and Lunathi Mngxuma. Each uniquely promising, all three photographers are alumni of an innovative social art project called Of Soul and Joy. The project’s inspiring backstory offers a window onto similar projects in South Africa, and elsewhere.

Established in 2012 in Thokoza, a low-income community southeast of Johannesburg, Of Soul and Joy offers its mostly school-age participants an introduction to photography.

Framed around two weekly classes led by photographer Jabulani Dhlamini (who is represented by Goodman Gallery), and backed up by intensive workshops directed by renowned photographers, the project aims to provide participants with basic camera skills.

In a community still haunted by the memory of internecine political violence in the early 1990s, as well as persistent poverty, the hope is that these skills will empower Thokoza youths both creatively and professionally. Promising participants additionally have the potential of receiving scholarships to tertiary institutions like the Market Photo Workshop in Johannesburg.

Of Soul and Joy photographers at this year's Investec Cape Town Art Fair

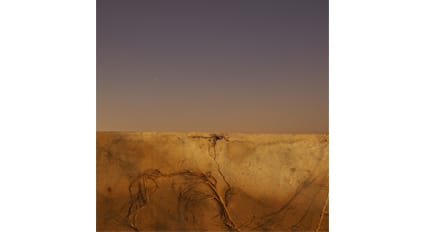

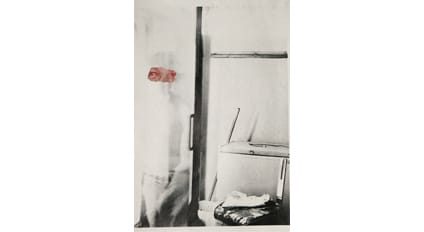

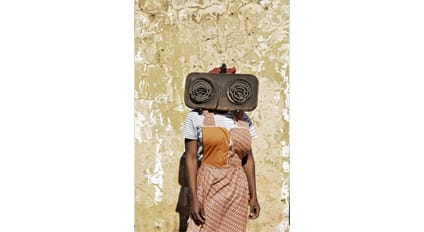

Sibusiso Bheka

Thembinkosi Hlatshwayo

Lunathi Mngxuma

Of Soul and Joy is one of three socio-cultural projects initiated and supported by Rubis Mécénat, an endowment fund created by French petro-chemical and logistics company Rubis.

Photography agents and dealers have enthusiastically responded to the work of star graduates like Lindokuhle Sobekwa and Sibusiso Bheka, whose work is on view at ICTAF.

Sobekwa joined Of Soul and Joy in 2012 and was mentored by photographers Bieke Depoorter and Mikhael Subotzky (also represented by Goodman Gallery). He was widely hailed for his gritty essay on drug abuse in Thokoza and in 2018 was invited to be a nominee of prestigious agency Magnum Photos. Bheka, in turn, had his innovative nightscapes exhibited in Mali, at the legendary African photo biennale Rencontres de Bamako, in 2017.

The choice of locale for the project, Thokoza, is not arbitrary. The settlement is near Easigas, a supplier and distributor of liquefied petrol that is majority-owned by Rubis. “A lot of people working at Easigas are or were from Thokoza,” says Lorraine Gobin of Rubis Mécénat. The hope, she adds, is that social art projects like Of Soul and Joy will enable lasting social art initiatives in communities where Rubis companies are based.

Art is a human investment

Social Impact Arts Prize

A similar concurrence of geography and corporate history underpins the creation of the newly launched Social Impact Arts Prize. The aim of the new prize is to award a socially engaged art project that has a “direct, measurable effect” on individuals and communities in the Karoo town of Graaff-Reinet.

The non-profit Rupert Art Foundation and the Rupert Museum in Stellenbosch support the prize, which is a clue as to the choice of site. Businessman Anton Rupert was born in Graaff-Reinet and throughout his career made the town a point of focus with his philanthropy.

Opened in 1966, the Hester Rupert Art Museum in Church Street houses an important collection of post-war modernist painters like Christo Coetzee and Walter Battiss. By contrast, the new art prize is a very different proposition to a static museum in that it actively promotes the concept of mobility, of being a “museum without walls” to quote the prize’s executive chairperson Hanneli Rupert.

It was the French philosopher and cultural minister Andre Malraux who coined the expression “museum without walls” in his book Le Musée Imaginaire (1965). In practice, in the water scarce community of Graaff-Reinet, the meaning of this imported concept is simple: the winning project has to be an instrument of social change.

“We believe that a prize of this type will draw attention towards arts practices which can point towards societal change,” said the prize’s director Roelof van Wyk at its launch in 2019.

Art projects that deliver real social impact

Six projects have been shortlisted for the award, the winner of which will be announced on 12 March at the Rupert Museum. A common theme of community and heritage, as well as food and water scarcity, links the shortlisted projects.

Architectural practice studioMAS and technology entrepreneur Gustav Praekelt have joined forces to propose a water-generating machine that also offers free internet access. Artist David Brits and music producer Raiven Hansmann have proposed a choir project as a tool to educate people about water resources.

Two projects are focussed on Graaff-Reinet’s indigenous plant life and its uses in medicine and food security. Kasthuri Naidoo and Ayesha Mukadam’s idea of seeding an indigenous food garden is not as fanciful as might seem as it connects with similar, successful interventions elsewhere.

Social Impact Arts Prize finalists

Hello Wolk!

By studioMAS and Gustav Praekelt, Hello Wolk! is a water-scarcity focused project that begins as an artwork, provides a certain amount of water, whilst also connecting to the community digitally.

PLANTed

PLANTed by Lorenzo Nassimbeni, Andrew Brose & Casper Lundie, is a public project which gives visibility to the loss of local knowledge of medicinal plants and recognising the under-represented disciplines of craft, tech know-how, local food culture, architecture and indigenous languages.

Tears Become Rain

By David Brits & Raiven Hansmann, Tears Become Rain is a mass choir programme in response to the climate crisis.

Mirage

Mirage, by Studio August, is a public-space, sculptural concept that will act as a meeting place for sharing and contemplations.

Revealing The City

Revealing The City, by Kim Lieberman & Paragon Architects, will use lace as a visual metaphor to reflect on the potential of an inclusive society where individuals lives are closely woven together, and also to resemble the complexities of our histories, politics and people.

The Long Table Project

The sixth finalist in the Social Impact Arts Prize is The Long Table Project by Kasthuri Naidoo & Ayesha Mukadam, that will look at sharing food as a means to rebuild connections across geographical and social boundaries. Communities will be invited to share in traditional food projects including an indigenous food garden, food heritage education and wild foraging.

“The time for protest has ended”

One of the most lauded is a two-decades-old project created under the umbrella Torolab. Founded in 1995 by Mexican architect and artist Raúl Cárdenas Osuna, Torolab’s base is a concrete bunker in Camino Verde, a poor hillside neighbourhood of Tijuana that is plagued by gang violence.

One of the features of the immediate landscape is a community vegetable garden tended by local families. The garden is a small aspect of Torolab’s broad range of activities. These activities are at once practical (food growing, culinary skills, computer training) and ephemeral (data gathering, media hacking).

“Part of our work is diagnostics, and protest is a diagnosis of something,” he said during a 2013 visit to South Africa about his data-interested, solution-driven approach.

Described as an “all around amazing thinker” by the Museum of Modern Art, where he has been a frequent speaker, Cárdenas Osuna has also travelled to South Africa on a number of occasions to speak about his art-inspired methodologies for creating social impact, most recently in 2019.

It is something he said in 2013, to a gathering a city administrators and town-planning officials in Ekurhuleni, that captures the urgency of social art projects in an unequal world. It is a favourite mantra of Cárdenas Osuna, one he has repeated often, but which doesn’t tire in its repetition. “The time for protest has ended; the time for proposal has begun.”

About the author

Sean O'Toole

Art journalist

Sean is a Cape Town-based journalist and editor. He's also a contributor to Investec Focus content for the Investec Cape Town Art Fair. He holds separate degrees in English literature, law, and creative writing.