Receive Focus insights straight to your inbox

Time has always fascinated us as humans. It may be because we are creatures who are aware of our own mortality and are therefore conscious of the constraints this imposes on us. Because we only have a certain number of decades on this planet, our time on earth should count for something, we tell ourselves. Time is, after all, an independent variable and a finite resource. We can’t create more time, nor can we store it for later use – it’s a classic use-it-or-lose-it scenario.

So we have to make our busy times as meaningful as possible and savour our “down time” as well. How best to do all of this has been the subject of many books, speeches, podcasts, TED talks, and courses. There are entire industries built around helping people to manage their time productively and meaningfully.

However, as we grapple with the concept of time, so we learn that time isn’t the simple, linear concept that we think it is. Albert Einstein’s theory of relativity seriously questioned the way we looked at it. He said that time and space are not the constants that we think they are and can be affected by how fast we are travelling or how far away we are from the centre of gravity.

Part of our problem as humans is that we see change in a linear way...

Subsequent research has shown how true this is. A team at the US National Institute of Standards and Technology in Colorado found that positioning two atomic clocks just a few feet apart above sea level revealed different time readings. Time really did go faster the higher above sea level the clock was (though the difference was tiny).

This is arcane stuff for us mere mortals to get our heads around. Moving to a bungalow at sea level isn’t going to buy us time in a meaningful way. Nonetheless, we deal with time’s relativity in other ways – metaphorically and perceptually – every day. A few everyday phrases highlight this: “Time goes by so fast when you’re having fun”; “Where did the time go?”; “It was as slow as a week in jail”. Anyone who has had to do exercises like “The Plank” will know that the final 10 seconds of a minute can seem like an eternity.

In short, our perception of time can make all the difference. It’s here where the philosophers, self-help specialists and mindfulness practitioners step in. They help us to appreciate the time we have available to us – over the short and long term. Some speak of managing our energy, rather than our time. We may find that we are more productive at certain times of the day, and less so at others.

The trick is to arrange our activities accordingly.

Read more: Why timing is everything

On the other hand, learning to think long term is also a skill that allows us to harness time to our advantage.

Here the famous phrase of Middle Eastern provenance (some attribute it to King Solomon, others to Persian Sufi poets) springs to mind: “This too shall pass”. The phrase reminds us of the transience of both good and bad times in our lives, encouraging us to appreciate the good while remembering that it won’t last; it makes us think beyond the bad times we are experiencing and to look to better times ahead.

This is particularly pertinent in the investment world. Markets are often subject to short-term shocks and bad news. Too often we get caught up in the noise as bad news comes to light and end up acting rashly and hastily when a more considered response would be best.

We also get caught up in the euphoria of rising markets, taking on too much risk and ignoring the warning signs. It’s better to look beyond the noise of the here and now and see the big picture.

The phrase also reminds us to use one of the most powerful forces in investment – the power of compounding. It’s been called the eighth wonder of the universe (again, the provenance is unknown, though some attribute it to Einstein) and for good reason: harnessing its power can be the difference between building a fortune and ending up with a pittance.

Compounding refers simply to allowing the earnings on your investments – dividends and interest – to be channelled back into your investment and build on a growing base. Compounding is particularly powerful when it takes place when planning for retirement, such as by investing in a retirement annuity, living annuity or other retirement structure. Tax on interest and dividends can be deferred, allowing all of the earnings to be channelled into growing the investment.

The key with compounding is to allow time to work its magic. While a couple of percent a year may not mean much over the space of a few years, the overall effect over a long period can be very meaningful.

Read more: Long-term investing: Make time your friend

But what about a world where change is happening so fast that time itself seems to be speeding up? Technological change (and other changes too, as we illustrate below) is happening at such a rapid rate all around us that it’s becoming harder for people and businesses to keep up, never mind get ahead.

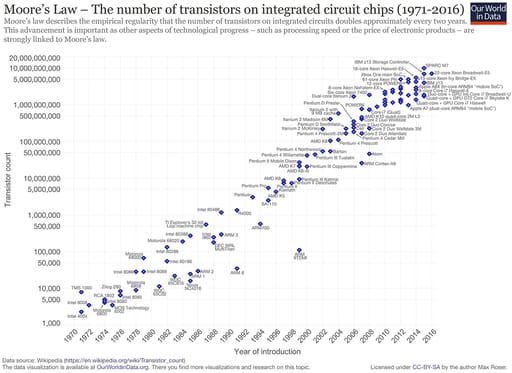

Part of our problem as humans is that we see change in a linear way – where things happen in easy-to-discern increments. But many things in the world change in non-linear, often exponential ways. Technology is a good example, where Moore’s Law has been a rule of thumb since the 1960s.

Intel co-founder Gordon Moore said in the 1960s that the number transistors that could be fitted into a chip doubled every two years, while the cost halved over that same time. While computer processing technology has changed over the years, the concept of continuous doubling in processing power and halving in costs, has held true since – and holds true of other technologies too, like solar power).

URL: https://ourworldindata.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/05/Transistor-Count-over-time.png; Article: https://ourworldindata.org/technological-progress; CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=71553709

The point about Moore’s Law and other forms of exponential change (and indeed compounding of earnings) is that it’s not always perceptible in the first few iterations. It’s usually only in the later iterations that we start to notice its raw power.

To illustrate this point, try this thought experiment. Imagine yourself walking at 2km/h. Now double your pace to 4km/h. A noticeable change but nothing unusual. Double it again to 8km/h, then again to 16km/h – you’re now moving briskly. Double it to 32km/h and again to 64km/h. Now you’re exceeding the speed limit on suburban roads. Another doubling to 128km/h and you’re exceeding the speed limit on the motorway. All of that in only six iterations, or doublings.

Technology isn’t the only thing that changes this way. So too do epidemics, ideas, and fashions. Barely perceptible at first except to the observant few, they suddenly burst onto the scene as if from nowhere, sweeping all before them.

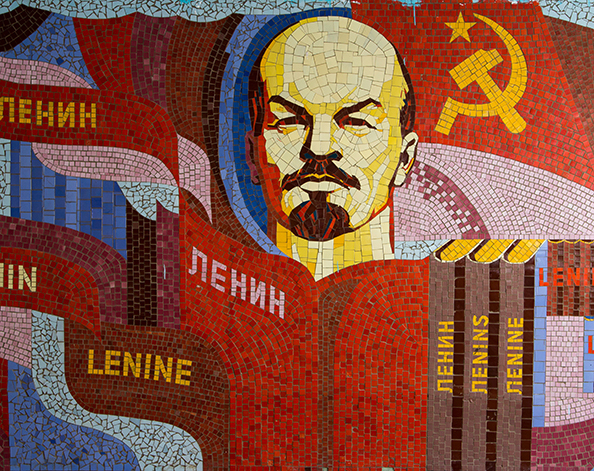

There are decades where nothing happens, and there are weeks where decades happen.

Vladimir Lenin was supposed to have said, “There are decades where nothing happens, and there are weeks where decades happen.” The quote is used to describe revolutions and the sudden toppling of long-established regimes – think of the fall of the Berlin Wall, the collapse of the Soviet bloc and the release of Nelson Mandela, all within a few months in 1989/90. But he could have been describing any movement or idea – whether in music, art or fashion. In the words of Victor Hugo, there is nothing more powerful than an idea whose time has come.

We humans can’t change time to fit our pursuits. But we can certainly change the way we perceive time and in this way manage ourselves better. If we can recognise in advance an idea whose time is about to come, we can certainly position ourselves to be on the right side of it when it arrives.