The UK government has set a deadline for ending the sale of new internal combustion engine cars by 2040. And although hybrid vehicles are currently exempt from this ban, this could change because governments are under pressure to bring forward that deadline to 2032.

Fully electric vehicles, or EVs, currently account for only 2.6% of new vehicle sales in the UK. Broad adoption of EV technology also faces significant infrastructure and logistical hurdles. It bears mentioning that even with the number of EV models proliferating, affordability is an issue for many people, especially because they remain scarce in the used car market.

Interim solution

Marc Elliott, equity research analyst at Investec, believes hybrid vehicles are essential. “I think they are an interim solution, but on a time scale that could be surprisingly extensive.”

This is for two main reasons: one is that, by 2021, CO2 emission standards for new car fleets in Europe will move from an average of 130 grams per kilometre (g/km) set in 2015 to 95g/km.

In practical terms, this means manufacturers will have to pay an excess emissions premium for each new car registered from the 2021 deadline if they miss the target. It doesn’t help that average CO2 emissions for new cars registered in Europe rose in 2018 to 120.4g/km, marking the second consecutive year that emissions rose.

The other reason is that when looking beyond 2021, average CO2 emission standards are likely to continue to tighten, with the European Commission proposing to reduce the 2021 limit for emissions by a further 15% from 2025 and by another 30% from 2030.

Manufacturers' dilemma

Car manufacturers have a limited number of options for getting their fleet average CO2 emissions down to levels that meet these standards. The idea of building more diesel-powered cars, which produce less CO2 than petrol, is unlikely to appeal to anyone because of ‘dieselgate’, where it was revealed in 2015 that car manufacturers starting with Volkswagen developed and installed software designed to cheat the emissions testing procedure.

Not only have sales of new diesel cars collapsed in the wake of that scandal, so has the secondary market for these vehicles. This is making many buyers wary of putting good money into new cars that they might not be able to resell. In addition, many cities in Europe and the UK are considering legislation to ban diesel-powered cars from city centres altogether because in real world conditions their emissions of Nitrogen Oxides (NOx) and particulate matter (PMs) are so much more toxic at ground level than petrol car emissions such as SO2 that they are considered a public health hazard. New diesels today are much cleaner in this context but it may too late.

“OEMs [original equipment manufacturers] know they’ve got to electrify, and investing more money in diesels doesn’t marry up with that strategy,”

Dead-end technology

Newly available mild hybrid diesel cars are on the market today. These combine a small battery with a motor-come-generator, capturing engine breaking to improve fuel economy by c.10%. However, plug-in, or full hybrid diesel variants are not widely available due to cost and complexity, particularly when trying to tackle emissions. Diesel engine emissions are much harder to treat than gasoline, particularly in an on/off context, as would be the case with a high degree of electrification.

Elliott believes that these mild hybrids are not solving the underlying issue to enable diesels to remain a key part of a fleet as they have been in the past. They improve efficiency but not enough.

“OEMs [original equipment manufacturers] know they’ve got to electrify, and investing more money in diesels doesn’t marry up with that strategy,” he says, particularly when they consider that any new engine technology requires a 20-year investing commitment.

Elliott is more optimistic about the prospects for hybrid petrol technology, particularly as plug-in hybrid electric vehicles (PHEV) become widely adopted. These vehicles benefit from a larger battery storage capacity than earlier ‘closed-system’ hybrid cars such as the Toyota Prius, allowing them to achieve potentially very good fuel consumption if they are regularly plugged-in between uses. Their CO2 emissions are also considerably lower – typically between 25-50g/km around 46g/km in real world terms.

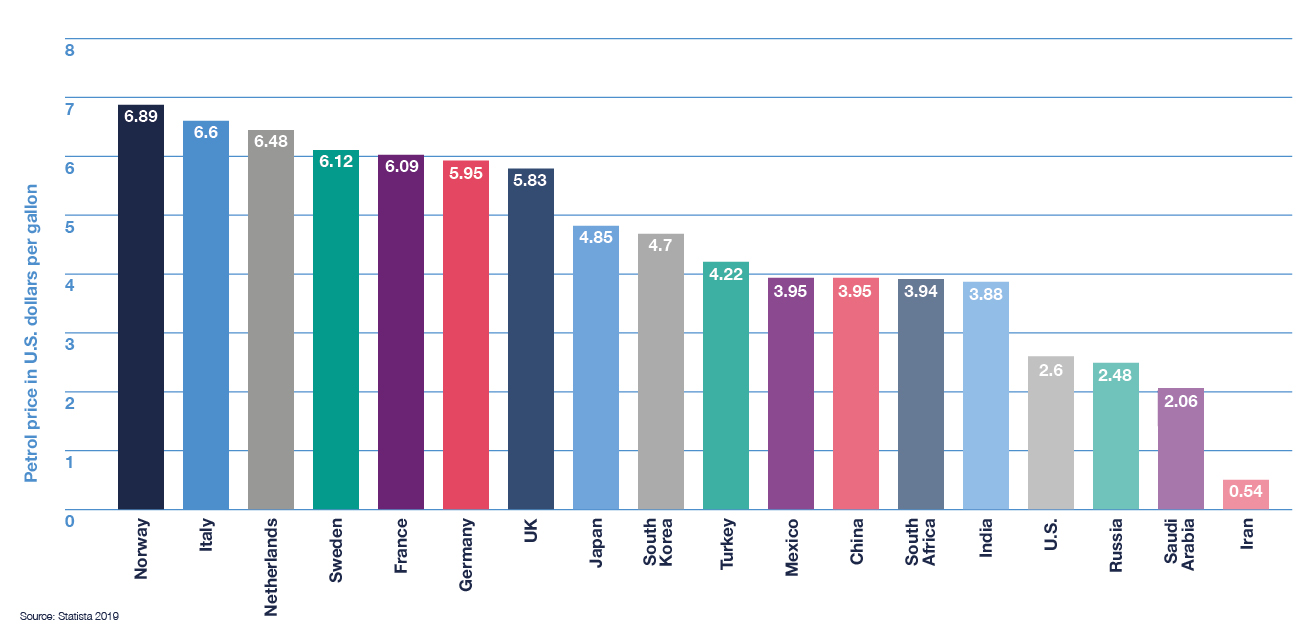

Petrol prices around the world in 2018

An attractive autonomous car option

Elliott believes this is important from a fleet perspective, because OEMs can use PHEV production to sharply lower average CO2 emissions across their fleets. This gives manufacturers a better chance of achieving their future emission standards, and avoiding the increasingly heavy penalties for breaching the targets.

From a commercial perspective as well, Elliott says PHEVs are likely to prove popular throughout Europe and the UK because of the potential savings on fuel, which is much more expensive here than in other parts of the world.

Additionally, as autonomous vehicles start to roll out, the operating efficiencies and extended range capabilities of PHEVs could even make them a vehicle of choice for fleet operators until a fully electric technology becomes widely adopted.

Achieving a zero-carbon transportation system by 2040 is likely to be accomplished in stages. While EV technology is advancing, logistical challenges to its broad adoption by consumers and fleet operators will take years to overcome. In the interim, a continuing role for hybrid vehicles, particularly plug-in models that are capable of operating without running their petrol-powered backup unit on shorter units, seems a prudent way forward for manufacturers.

While cars are making headway to being fully electric, there are smaller steps being made towards a successful adoption of an electric HGV fleet. Progress is underway, most recently Daimler Trucks North America delivered the first of its electric Freightliner eCascadia Class 8 trucks in August. Two carriers, including NFI, each took one of the eCascadias into their fleets and will use them in drayage operations at the ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach.

Despite positive moves, Marc Elliott believes that more work needs to be done for the adoption of an electric fleet in the UK; “While the adoption of electric cars are making swathes, for HGVs the battery technology is still needing improvement.

The eCascadia battery provides enough energy for approximately 250 miles, so this is useful for local distribution of goods that battery power is suitable for.

The low energy density of batteries vs fuels is a significant issue for longer range applications where fuel cells and hydrogen are likely more suitable in a decarbonisation context. Charging times and durability are also issues to contend with as commercial vehicles are often higher mileage higher usage activities than passenger cars. But it’s great to see steps being made in electrifying the fleet.”

Marc Elliott

Equity Analyst - Energy

Browse articles in

Please note: This page is provided for information purposes only and should not be construed as an offer, or a solicitation of an offer, to buy or sell financial instruments. This page does not constitute a personal recommendation and is not investment advice. Any predictions, or forecasts expressed are based on significant judgement and analysis of available information at the time of writing and actual outcomes may be materially different and may be affected political, economic or any other relevant circumstance changes