A bullish case for oil and integrated European majors

With a strong case for further upside risk to oil prices in the near term, there are some very attractive opportunities in this space.

There are good arguments for further upside risk to oil prices in the near term. Declines in Venezuela and other more mature basins will continue just as Iranian sanctions bite. With US producers hamstrung by offtake bottlenecks, Saudi will struggle to keep OPEC production flat and the global market in balance.

At the same time oil equities are valued off longer dated prices which are $15/bl below SPOT and, even using these prices, the stocks still discount value destruction. There are some very attractive opportunities in this space.

Go to Google Maps and look at a satellite image of West Texas.Zoom in until you see a lattice of service roads linking rectangular patches of bare desert. It won’t take long to see this pattern, it dominates the landscape.

Zoom closer on an individual patch and you will see the shadow of an ubiquitous Texan totem, the nodding donkey oil pump. This exercise will give you some idea of just how familiar and comfortable Texas is with large scale oil production.

It will also give you some idea of how much drilling has occurred in Texas overmore than 100 years, and how well Texans know their own geology. These are vital attributes for the state and its inhabitants.

They can adapt and thrive as last century’s ‘Texas Oil Boom’ is followed by a modern sequel, ‘The Shale Revolution’. A thirsty worldBefore we get into the astounding growth of onshore US oil and gas production, it is worth recapitulating why this industry matters.

Surely with cheap solar power, wind, biofuels and the growing sale of electric vehicles, the increasing investment in electricity storage, self-conscious governments and conscientious consumers, hydrocarbons are a relic, an arcane and damaging source of energy?

Don’t substitution and a history of value destruction prejudice investment in the oil industry? Without hesitation, our answer is no.

We may be keeping a lid on our hydrocarbon demand... but this is not enough to arrest global demand’s upward trajectory.

From a privileged position in the Western World, where technology is relatively cheap, and where primary energy makes up only 5-10% of our consumption basket, it is easy to forget that 6 billion people are living in regions where urbanisation and development is rapid, where primary energy consumption is growing, where price sensitivity is high and where infrastructure is in its infancy.

We may be keeping a lid on our hydrocarbon demand, diluting consumption per capita or per unit of GDP, but this is not enough to arrest global demand’s upward trajectory.

Estimates for Global Crude Oil Demand, million barrels per day

Demand growth has come from the emerging markets and is forecast to continue

Source: BP Annual Statistical Review 2018

Productivity, efficiency and policies targeting new technology globally are admirable and will eventually precipitate a full switch out of hydrocarbons (when the combination of new business models and technology achieve critical mass) but in aggregate these efforts subtract only about 2% from global energy intensity annually.

In other words, ceteris paribus, with global GDP growth of 3.5%-4%, oil demand growth will be 1.5%-2% for the foreseeable future. This analysis explains why most institutions do not forecast peak oil demand before 2040.

Add a decline rate of 3% to this growth and the industry must increase production by about 5% every year to meet demand. The only way to deliver this growth is by offering attractive returns on capital to the industry.

For this reason we think oil and gas prices will remain above marginal cost of supply and that hydrocarbon companies will generate value in both the short and the medium term. There are compelling reasons to search for investment opportunities in the space.

The search

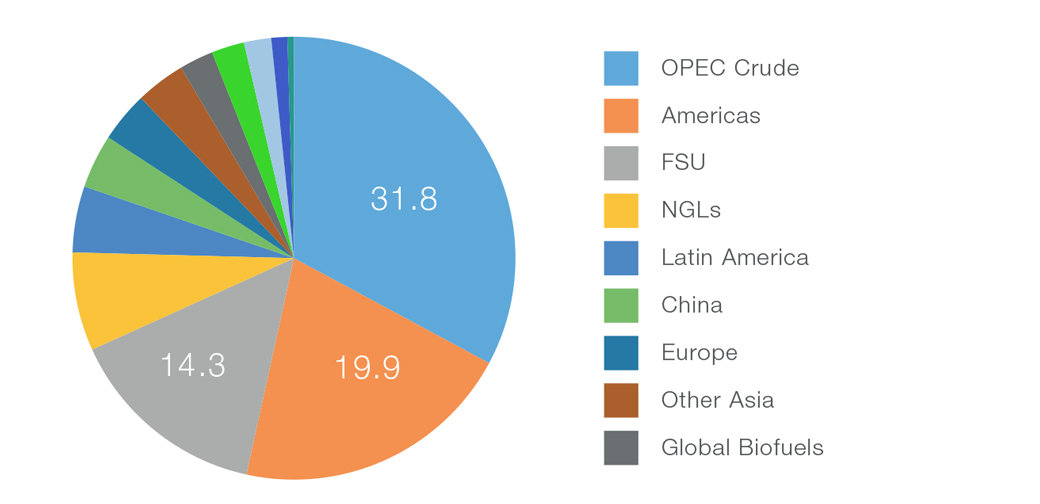

So where do we begin our search? Where does this supply originate and who benefits most? Of the 99 million barrels per day (m bpd) global market, OPEC, North America and the Former Soviet Union account for about 2/3 of production.

Saudi (10m bpd) is almost a third of OPEC production, lower 48 (non-Alaskan) US (also 10m bpd) is about 40% of North American production and Russia (at 11m bpd) accounts for the bulk of the FSU.

Global Crude Production, m bpd

In a 99m bpd global market the camel, the eagle, and the bear dominate

Source: Investec Wealth and Investment, Bloomberg

To borrow another analysts' idiom, ‘the camel, the eagle, and the bear’ dominate. These are not only the largest players, but along with Brazil, these are the only countries producing more than 1m bpd who have consistently increased production in the past decade.

These are the countries where a favourable confluence of politics (fiscal imperatives) and economics (low cost) mix into a blend rich enough to nourish investment. It is our view that these jurisdictions will deliver the volume required to satisfy demand in the next few years.

Big, fast, fit

Let’s start with the US; its shadowis long enough to affect productiongrowth and prices globally, and theUS industry is now big, fast and fit.

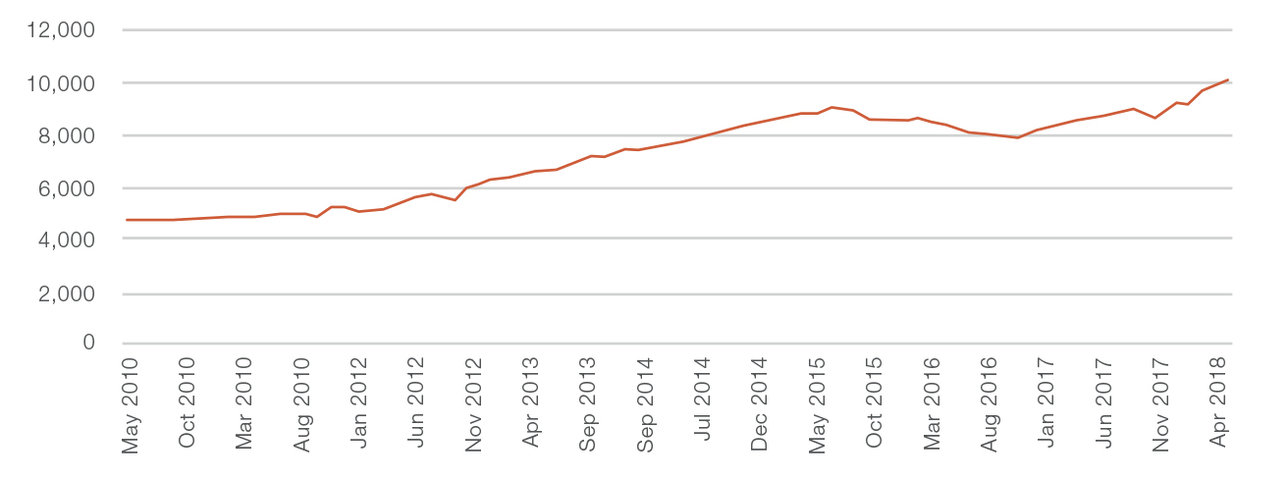

US Lower 48 Crude Production, 000 bpd

Large and rapid production increases in the US, a new paradigm, the adoption of unconventional drilling techniques

Source: Investec Wealth and Investment, Bloomberg

As recently as 2012 onshore US oil production was about 5m bpd. This year it will exceed 10m bpd. By drilling unconventional oil, US producers have, in a mere six years, added more capacity than Iraq. It is not only the scale of US production that needs contextualising, but its speed.

It has taken Russia eight years to increase production by 1m bpd and it took four years for Brazil’s Santos basin to break 1m bpd. In addition, in the past three years the US industry has also been working out, building lean muscle.

Cost declines of 20-25%, driven by operational improvements, supply chain optimisation and technological adoption, have moved onshore US production firmly into the most cost-competitive zone of non-OPEC production.

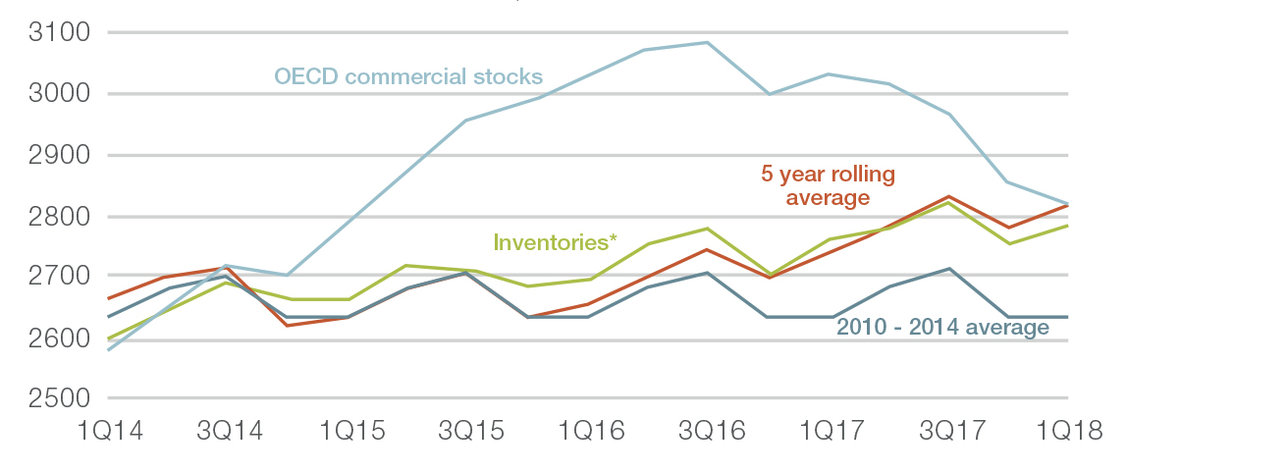

OECD Commercial Inventories, m bls

The ‘glut’ in 2015 becomes excess inventory, finally normalised byOPEC curtailment discipline

Source: BP statistical review 2018

At first, declines in Libya, Syria and Iran insulated crude prices from this surge, but by 2015 abundant supply found its way into global inventories, and when OPEC refused to balance the market by curtailing production, the floor dropped from under the market, with oil prices hitting $28 per barrel in February 2016.

The OPEC (+ Russia) production curtailments agreed in 2016 have bought inventories back down, but to outline the future production landscape we only need glance at US production again for clues. In the past 18 months the normalisation of inventories and the recovery in prices has stimulated yet more US supply. In this short period, the US has lifted production by another 2m bpd.

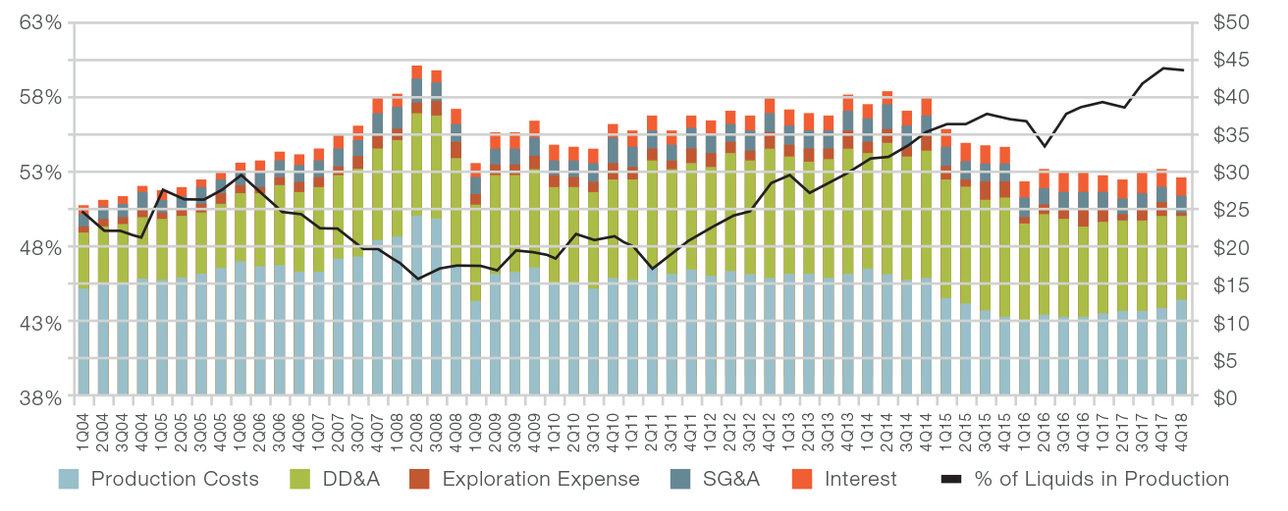

US Upstream Costs, $/bl (oil equivalvent)

$12/bl total cost reduction in the last 4 years. Now in the first and second quartile of global ex OPEC cost curve

Source: Bernstein Research

Bottlenecks, burnt fingers, buffers

So how can we make a bullish case for oil, with such a big, fast, fit player standing on the touchline? Well, first, his shoelaces are tied together: there are pipeline and infrastructure bottlenecks limiting US offtake for the next couple of years. This bottleneck manifests as a discount between inland and coastal prices, which is currently >$15/bl.

Second, the mere threat of this opponent is scaring other players from the field. In a market where cheap supply can be bought on in such a short period, it is difficult to justify large capital projects with long lives elsewhere.

The risk of owning stranded assets and of gross value destruction is just too great; recent memories of fingers burnt are all too fresh. Only investments at the lowest end of the cost curve will receive Final Investment Decisions (FID).

US Crude Oil Differential, West Texas Intermediate (WTI) vs Midland, $/bl

The shoelaces of US producers are tied. Bottlenecks manifest in differentials between inland and gulf coast prices

Source: Investec Wealth and Investment, Bloomberg

Compounding supply issues, OPEC does not have that much spare capacity any more. Supposedly Saudi has capacity of 12.5m bpd, but they have never produced more than 10.6m bpd. Following the latest OPEC+ meeting in Vienna, Saudi is ending its production curtailments, meaning it will soon get back to its peak.

But this move barely offsets precipitous declines in Venezuela, and if Iranian sanctions bite we could lose another 1m bpd and Saudi may struggle to fill the void. It is not by design that OPEC has managed to comply and exceed its targeted production curtailments.

Venezuela’s population and crude oil production are suffering the results of socialist expropriation, chronic underinvestment and debt. Venezuelan adults report losing, on average, 11kg in the past year. Oil production has almost halved to 1.4m bpd. Neither metric is likely to rise any time soon, and only then following revolutionary political change.

The precarious market balance is highlighted by Trump’s latest Twitter tirade, demanding Saudi increases production by 2m bpd. He is attempting to limit the damage of (or to divert the blame for) high gasoline prices for US consumers as he attacks Iran with fresh sanctions.

The precarious market balance is highlighted by Trump’s latest Twitter tirade, demanding Saudi increases production by 2m bpd.

If Saudi doesn’t have enough spare capacity, and Trump pushes too far, then the buffer of global supplies will be dangerously thin. And there is no help elsewhere. There is growth in Russia, and the ramp up of the Santos pre-salt, offshore basin in Brazil is also delivering growth.

This output is the result of consistent investment, the profile is relatively predicable and incremental, so we can see that it is unlikely to offset the many other regions that are in decline, especially as these declines are accelerating as the effects of the 2015/16 capex diet kick in.

On that list: the North Sea (3m bpd), West Africa (5.5m bpd), North Africa (2m bpd) Mexico (2m bpd) and Asia (6.5m bpd). Finally there is no insulation from inventories. As we saw in earlier charts, stocks are at their five-year average and, at 60 days of use, any supply imbalances and inventory draw could cause major market volatility.

Flowing opportunity

Tight markets, with thin inventories and risks to supply, support near-term prices and present opportunity. Integrated oil companies will generate extraordinary cash flow and, if they maintain capital discipline, they will harvest the benefits capex deployed late in the last cycle. Absent a sudden decline in demand due to an economic shock, there is an opportunity to compound big cash returns and to benefit from a significant re-rating.

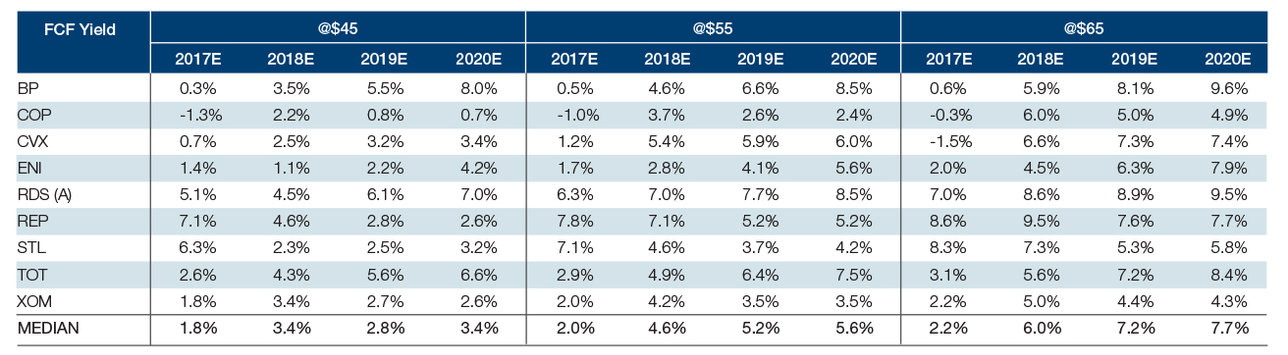

Integrated Oil Majors’ Cash Flow Yields, %

At current oil prices some are making double digit FCF yields

Source: Citigroup Research

All integrated major oil and gas companies now preach the same canon: we will be disciplined, we will return cash to shareholders, we will make investment decisions with only the longest time horizons and only the most conservative price decks in mind.

The cash building daily on their balance sheets may test their conformity, but they are unlikely to break ranks yet. The European integrated oil companies are in a particular sweet spot. Their global footprint means they don’t suffer from low realisations.

The European integrated oil companies are in a particular sweet spot. Their global footprint means they don’t suffer from low realisations.

They achieve Brent prices rather than West Texas Intermediate (WTI), they don’t wear inland differentials, they have the complexity in the downstream to handle abundant light sweet crudes, to capture favourable refining margins, and they also have gas and marketing divisions designed to capture rich global arbitrage opportunities.

Industry-wide capital discipline and attractive pricing will also help other specialists further downstream: producers, service companies and industrials occupying attractive niches. Examples are likely to include specialist low cost operators in mature basins, infrastructure and equipment companies in the US and companies specialising in Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG) marketing and Floating Production Storage and Offloading (FPSO).

This party might end with a bang as US product finds a new route to market, or as the benefits of misbehaviour encourage companies to over-spend. After all, the cure to high prices remains, as always, high prices. But our analysis suggests the main act has yet to come to the stage. Enjoy the show.

Discover how you could benefit from our wealth management services for private clients

Search articles in