Receive Focus insights straight to your inbox

Consistent improvements in the economic welfare of the average person have now been sustained for centuries in the western world. The improvement in global per capita incomes has been especially impressive over the past 70 years, as the process of economic growth has been extended more widely.

Since 1950, the world population has increased spectacularly from two to over seven billion, while the number living in absolute poverty has declined to about one billion

Global GDP per head in inflation-adjusted terms has increased on average by about four times since 1950. The world population has increased spectacularly from two to over seven billion over this period, while the number living in absolute poverty has declined to about one billion. Economic history has proved to be not at all dismal.

It is the sum of the efforts made by billions of economic actors to do as best they can for themselves and their dependants that leads to higher levels of national production and incomes. Governments can either help facilitate this process or inhibit it.

We might summarise these essential conditions for economic development as that of cultivating economic and political freedom. That is to say, allowing individuals to pursue their interest in higher incomes with as little interference and obstruction from others – to provide the economic actors with freedom to buy and sell, to employ or be employed, to hire or rent, to save and invest largely as they see fit; to be able to freely set up new businesses with new methods and offerings to compete with the established firms, and to close them down easily when circumstances demand.

Law and order, and the rule of law, are essential ingredients that support free economic action

Most importantly, these conditions include being able to protect these freedoms and the savings and wealth they generate from arbitrary expropriation or violent extraction by other individuals or the government. Law and order, and the rule of law, are essential ingredients that support free economic action.

Why, then, do so many countries fail to adopt the right mix of rules and regulations required for economic progress, even as other countries do better at compounding, ever higher, the incomes and living standards of their citizens, including those of the poorest 20% of their populations?

Economic freedom supports a general interest in a stronger economy. Unfortunately, groups with powerful resources may well prevent it from happening. Those with a valuable stake in the system, as it is, will always be threatened by the competition for their customers or suppliers, or for their power to order others around.

Those with government-favoured ethnic or religiously-based credentials that allow them to do business or find employment on preferred terms, will resist the competition that might reduce their incomes and influence. They may have valuable licences that keep out the competition – local and foreign. Or they may have preferred access to mineral or land rights of great value. The government officials responsible for administering the rules and regulations that govern economic activity will also have an economic interest in the form of well-paid secure jobs with above average benefits, especially pension rights. They are not natural reformers.

Ranking freedom and economic freedom

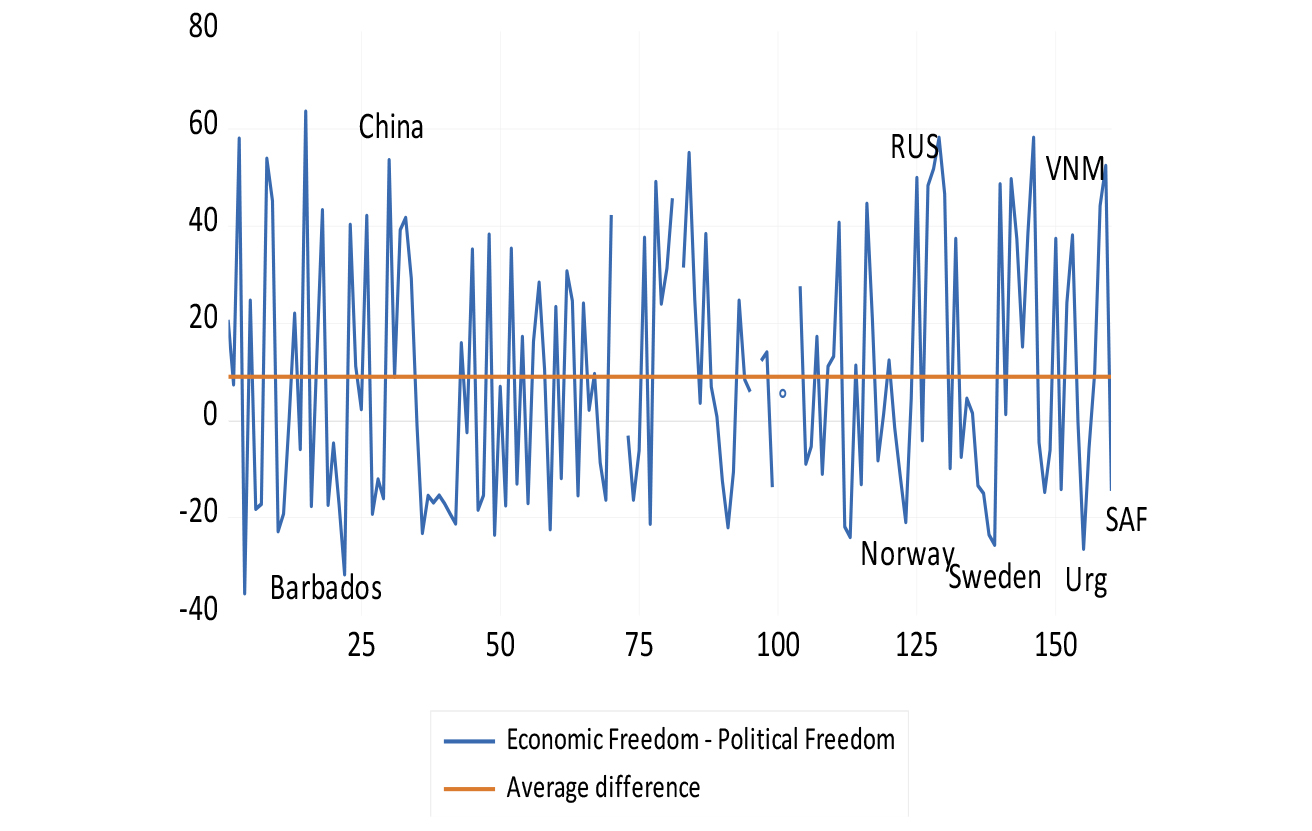

Freedom House has long compared the degrees of democratic freedoms enjoyed across countries. The Fraser Institute in Canada has pioneered the comparative measurement of economic freedom. The ranking order of the countries scored for economic freedom by the Fraser Institute and for freedom measured by Freedom House is well correlated.

Finland, Norway and Sweden register a maximum of 100 points for political freedom

A relatively high score for economic freedom may, however, be enjoyed without much political freedom, as for example in the cases of China, Russia and Vietnam. Singapore, according to Fraser, is the freest economy (88.4 points), but only is credited with 51 points for political freedom by Freedom House. The Scandinavian countries among others score well on both – but relatively better on the political front, where Finland, Norway and Sweden register a maximum of 100 points for political freedom. Their scores for economic freedom are in the mid-seventies. The US achieves a score of 86 for political freedom and an impressive – but not world beating - score of 80.3 for economic freedom.

Political freedom without a high degree of accompanying economic freedom appears very unlikely. When given the opportunity to choose, the people have voted for a high degree of economic freedom. Experiments with top-down economic planning (in the Soviet Union, China and Cuba, for example) revealed that it takes the repression of democratic freedoms to deny economic freedom.

The difference between the Fraser score for economic freedom and the Freedom House score

(A score of above zero indicates relatively more economic than political freedom and vice-versa. The above the line differences are greater than those below the line)

Source: Fraser Institute, Freedom House and Investec Wealth & Investment

SA, unsurprisingly, scores poorly for economic freedom and better, though not outstandingly well, for political freedom. Its score of 64.5 for economic freedom gives it a low rank of 110 out of 160 countries. This score has declined in recent years. SA’s score of 79 for political freedom places it in the second quartile of free countries.

The higher-income countries register well on the economic freedom scale despite the strong tendency for their governments to collect not only more taxes, but for their taxes to command a higher proportion of their (higher) GDPs. Clearly, the more tax paid out of incomes, the less freedom left over for individual taxpayers to exercise their own economic freedoms.

The high-income countries are typically not shy to regulate economic activity, however, they appear to regulate better than the bulk of lower-income countries, according to the Fraser metrics. Their regulations are judged as more transparent and predictable, and less vulnerable to corruption.

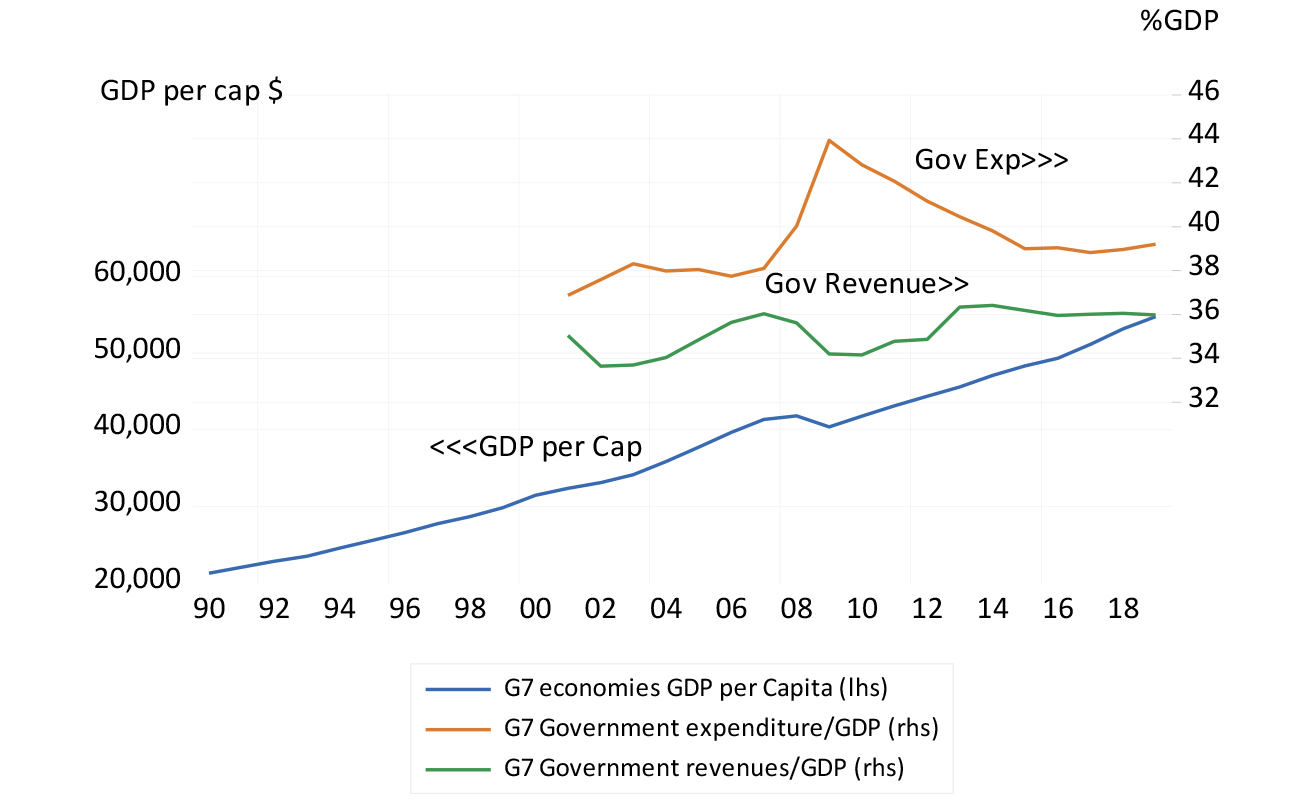

It would appear however that the share of GDP taken in taxes by the governments of the most advanced seven economies, the G7, may well have stabilised. The global financial crisis and the accompanying decline in GDP saw the government spending ratio rise and the ratio of taxes to GDP decline. More recently, the ratios have stabilised at their pre-crisis rates.

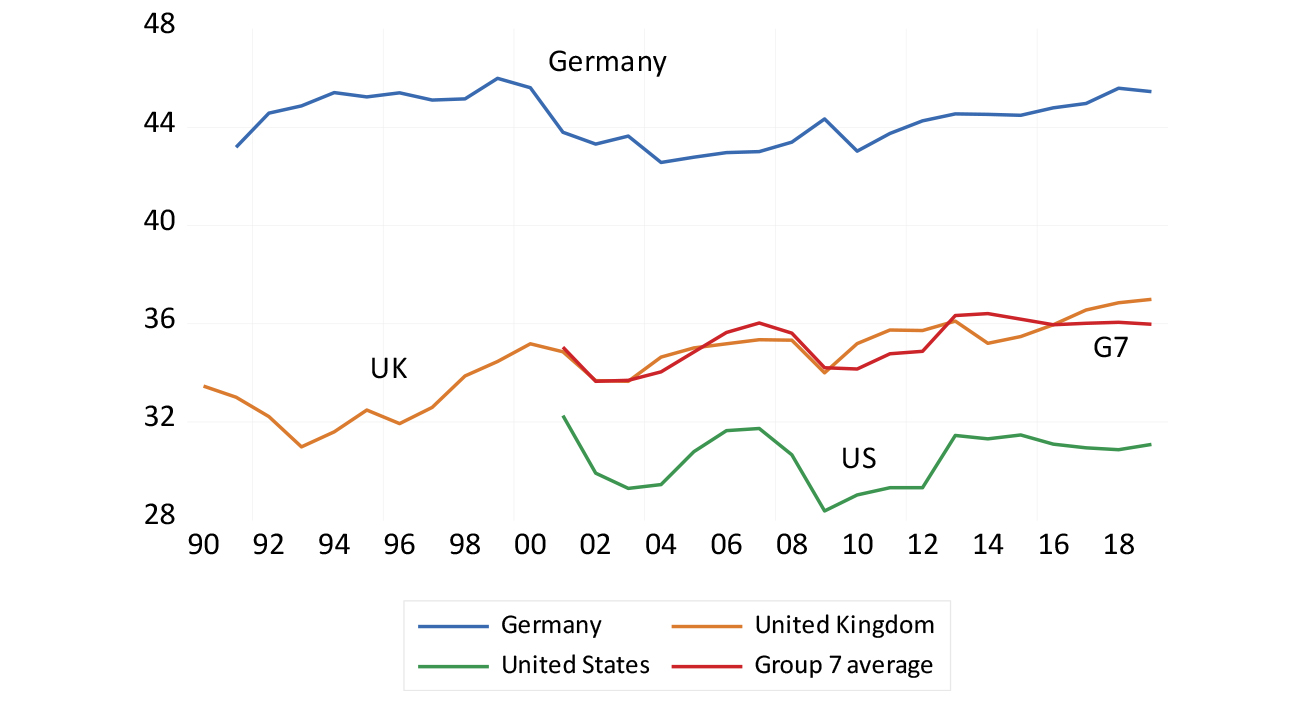

Perhaps this indicates the influence of mobile taxpayers (corporations and wealthy individuals) who can choose their domiciles to some degree. Competition for mobile taxpayers may help restrain tax rates in ways that promote economic growth and serve to increase the amount of tax collected. Germany is a demanding and large tax collector while the US, combining all levels of government taxes, taxes comparatively lightly.

Most advanced economies (G7) GDP per capita, share of government expenditure and revenue in GDP

Source: IMF, WEO and Investec Wealth & Investment

Germany, UK and US: Tax revenues as share of GDP

Source: IMF, WEO and Investec Wealth & Investment

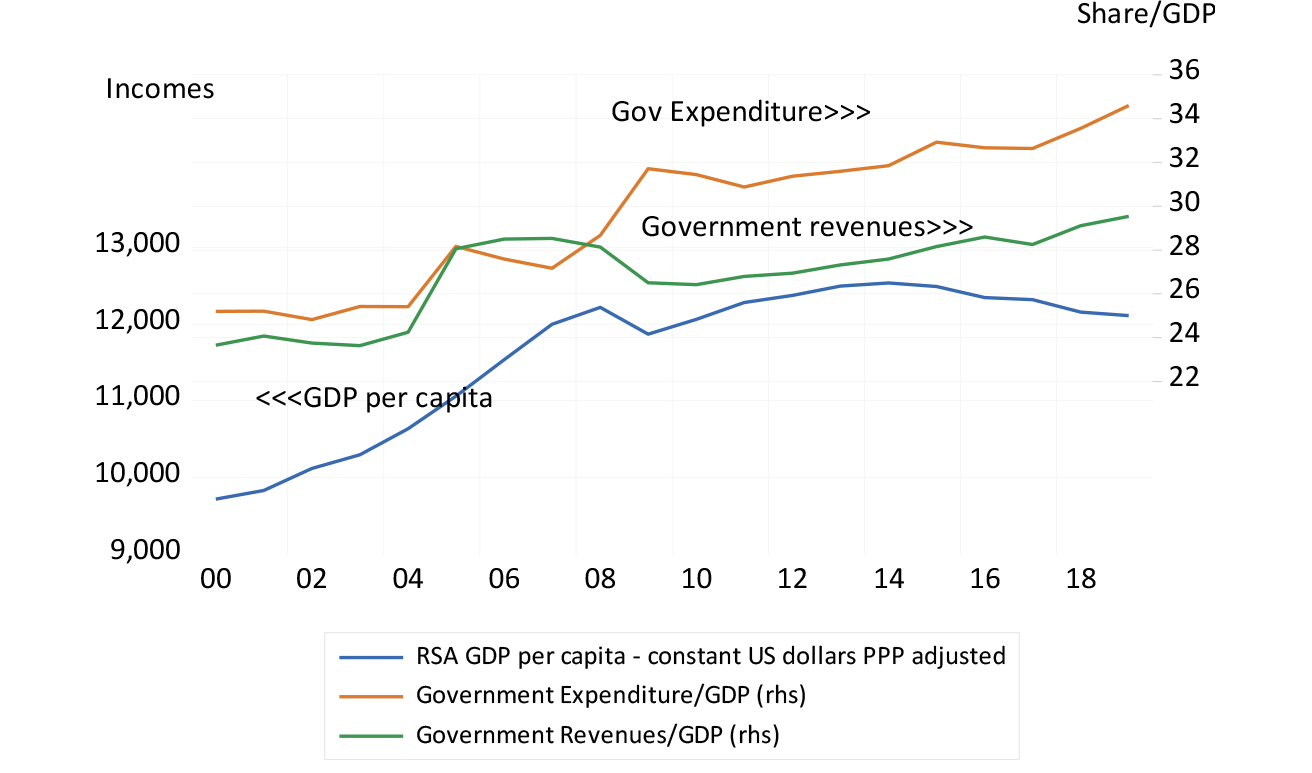

The equivalent SA trends have been moving in the wrong direction for freedom and economic growth. The ratio of government spending and tax revenues to GDP (less over for the exercise of economic freedom) have been increasing, while per capita GDP has stagnated since 2010.

SA GDP per capita (in US dollars), share of government expenditure and revenue of GDP

Source: IMF, WEO and Investec Wealth & Investment

SA’s inability to restrain the upward march of government spending, given the weakness of the economy, has led to higher tax rates – and a larger share of taxes in GDP. The higher tax rates intended to close the gap between government spending and revenues have, in turn, discouraged economic activity and depressed tax collections.

As with all countries, choosing less or more economic freedom will determine the progress of an economy and the economic fate of its most vulnerable citizens. We can only hope that SA, given the bleak alternative of persistent economic stagnation, makes more of the right freedom-enhancing choices.

About the author

Prof. Brian Kantor

Economist

Brian Kantor is a member of Investec's Global Investment Strategy Group. He was Head of Strategy at Investec Securities SA 2001-2008 and until recently, Head of Investment Strategy at Investec Wealth & Investment South Africa. Brian is Professor Emeritus of Economics at the University of Cape Town. He holds a B.Com and a B.A. (Hons), both from UCT.

Receive Focus insights straight to your inbox