Summary

Global

With the epicentre of COVID-19 shifting to Europe, governments in the Western hemisphere have implemented drastic containment measures. Some of the near-term downside pressures may be mitigated by enormous amounts of fiscal and monetary stimulus. Still, a more significant risk is that the sharp dip in activity becomes a prolonged slump.

It is next to impossible to gauge the magnitude and longevity of the downturn at this stage. We expect stabilisation in China in the second quarter. Elsewhere timings may vary, but we broadly expect recoveries to begin in the third quarter. We now look for a worldwide contraction of 0.5% in 2020 (we previously predicted growth of 2.8%) to be followed by expansion of 3.9% in 2021 (previous forecast 3.5%). But we expect that we will have to revise these numbers frequently.

United States

Usually, by the spring of a presidential election year, the primary races are in full swing, but COVID-19 has overtaken this year’s events. Many Americans are on lockdown, creating enormous disruptive forces to US economic activity. The US administration, after resolving cross-party disagreements, now looks to be gearing up to unleash a $2 trillion stimulus package to try and prevent the current disruption turning good business into bad, triggering a ricochet across the economy.

The Federal Reserve has acted aggressively too with 150 basis points of rate cuts in totality alongside open-ended quantitative easing and other initiatives. The scale of the action should help to break the economy’s fall. Even so, we are pencilling in a gross domestic product drop of 3.9% this year and a rise of 2.5% next. These remain under review amidst an evolving situation.

Eurozone

While China was the original epicentre of the coronavirus outbreak, developments in the euro area have quickly escalated, with the number of confirmed cases reaching 200,000. This, combined with the stringent containment measures, is set to lead to an unprecedented sudden stop in economic activity, as evidenced by the March Purchasing Manager Indexes.

We suspect that the extent of the downturn in the first half of 2020 is likely to exceed that of the 2008-09 financial crisis. On the assumption that the COVID-19 outbreak does not have a prolonged impact, we have materially revised our euro-area GDP growth forecasts, which now see the region's economy contracting 5.6% in 2020. In 2021, we expect growth of 3.5%. Despite the bleak outlook for 2020, it is worth noting that the outlook could be much worse without the significant and timely monetary and fiscal policy measures.

United Kingdom

While infections have increased at a more modest pace than some European nations, a nationwide lockdown has been implemented to try and slow the spread of the virus. The government and the Bank of England have closely coordinated to try and mitigate the economic fallout, but a deep recession is inevitable for the first half of the year at the very least.

How long the social distancing measures will remain in place, and whether they will be tightened is uncertain. But assuming that they are eased in the summer, activity should rebound in the second half. On this basis, we look for GDP to contract 4.4% in 2020, followed by expansion of 3.3% in 2021. Amidst this disruption, striking a new UK-European Union trade agreement by year-end appears increasingly optimistic. It, therefore, seems likely that the transition period will be extended beyond 31 December.

Get Focus insights straight to your inbox

Global outlook

COVID-19 has turned the global economy upside down as the virus has gained a foothold in the Western hemisphere. Indeed, China now accounts for just 18% of the world’s total cases. The epicentre of the outbreak has moved to Europe. A global tally of 439,940 infections and 19,744 fatalities has brought severe containment measures from governments worldwide.

It is these policies, including full lockdowns in some areas, which are hampering economic activity. Governments and central banks globally are providing enormous amounts of stimulus to try and reduce the risk of a period of significant disruption turning into a pronounced downturn.

READ MORE: QE comes to SA as Reserve Bank steps in to provide liquidity to the market

Astonishingly, world equity markets were at record highs as recently as six weeks ago. Since then the MSCI World Index has plunged 28%. While markets have principally been guided by COVID-19-related newsflow and rose robustly on the progression of the US fiscal stimulus, it seems likely that economic data will become more prominent now as investors seek clues on the depth and duration of the downturn.

One view is that a turning point (i.e. a slowdown) in the number of new cases could be the trigger for the all-clear in risk assets. We are more cautious. This condition seems necessary, but not sufficient. Markets will likely need to see evidence that, what will inevitably be a global recession, is not protracted.

Equity market volatility has been prominent. Equally important has been moves in bond markets. Notably, 10-year US Treasury yields rose by about 70 basis points in a fortnight, reaching a high of 1.18%. Those on gilts climbed by about 60 basis points. In short, "safe havens" were no longer considered safe. Signs of broader market dislocation were mounting, including wider bid-offer and inter-instrument spreads.

An example (frequently cited in 2008) is LIBOR/OIS, where spreads remain elevated. Recent moves were beginning to look like 2007-08. This acted as a catalyst for major central banks to re-open or increase QE programmes and introduce new liquidity schemes.

Gold has been a puzzle, fading from a nine-year high of $1,680 in March to $1,610 now. Reports point to sales of gold holdings to meet margin calls in other assets. Meanwhile, industrial commodities have reacted predictably to the prospect of a global slump. Pressured also by infighting oversupply across producers, Brent crude has more than halved to below $30 per barrel.

Copper, currently at $218/lb, is 24% lower. The USD is currently "enjoying" safe haven status. Other than currencies to which it is pegged (e.g. the Hong Kong dollar), it is difficult to find a currency that has been stronger so far in 2020. US President Donald Trump’s evident dissatisfaction has led to some speculation over US intervention to drive the greenback down.

Maintaining company cash flow is critical, particularly for small firms, as shedding staff and cutting corporate spending would result in an economic doom loop.

Fiscal policy is playing a massive role alongside monetary policy. Bolstering demand may mitigate some of the near-term downside pressures. But the vital aspect is to prevent a sharp dip in activity becoming a prolonged slump. Here maintaining company cash flow is critical, particularly for small firms, as shedding staff and cutting corporate spending would result in an economic doom loop.

Efforts by the US and UK (among others) to pay for furloughed workers should be seen in this respect. Central bank programmes to keep markets functioning are keeping credit flowing further up the chain. In these respects, government and central bank policies are joined up.

Putting together a "bottom-up" global GDP forecast is next to impossible. We do know that recent PMIs have plunged to all-time lows. Also, Chinese industrial production was 13.5% down on a year ago in the combined January-February period. Broadly we expect stabilisation in China in the second quarter, then a rebound.

Elsewhere timings may vary, but we see the eye of the downturn in the second quarter before recoveries begin in the third quarter. Our pencilled in world GDP forecasts are now -0.5% for 2020, down from 2.8% last month. If (and we stress if) global policy measures do gain traction, we may see growth of 3.9% in 2021 (previously 3.5%). But we expect to have to revise these numbers frequently.

United States

During a usual election year, the presidential nomination races would be hotting up right now. Instead, primaries are being postponed amidst the COVID-19 pandemic. However talk that Mr Trump might delay the election itself looks to be just that, with Federal laws setting election day as “the Tuesday next after the first Monday in November,” while the 20th Amendment provides that the president’s term ends on 20 January 2021.

Most attention is on COVID-19, which has spread like wildfire in densely populated areas. Indeed, New York accounts for nearly half of America’s infections. Cases are now increasing at a faster pace than any other nation with the WHO warning the US could become the epicentre of the outbreak.

The US now has a “lockdown” in place affecting large segments of the American public. Treasury Secretary Steve Mnuchin has indicated this is likely to remain in force for 10 to 12 weeks. We can be sure this will have a hugely detrimental impact on economic output near-term.

We await news of the final stimulus package from the US administration, which at the time of writing looked set to be around $2 trillion

Trying to predict by how much, to any degree of accuracy is impossible. For now, our best guess is that we will see the US economy contract by a bit more than 20% (saar) over the second quarter but with a recovery evident over the third and fourth quarters.

But we would not wish to present this without clear warnings over the range of possibilities. One of the earliest signals of the economic disruption comes from the Philadelphia Fed Index and Empire State Survey, with these two manufacturing gauges witnessing their biggest drops on record.

Our US GDP forecast for this year is now -3.9%, but under constant review as the situation unfolds. We also await news of the final stimulus package from the US administration, which at the time of writing looked set to be around $2 trillion (approximately 10% of annual US GDP).

The idea of the stimulus package (alongside the Fed policy action) is to stop the period of significant disruption shifting into a self-fulfilling downturn, such that when isolation stops, the economy can pick up where it left off. The spike in jobless claims seen in the last week, sizeable as it was, will be nothing compared to those likely in current weeks.

The Administration Bill, when it comes, will direct more cash to small businesses to slow the tide of layoffs, while there is also discussion of direct payments to adults and children. Fed action has been aimed at ensuring that otherwise good businesses can remain afloat and are not shut out by disruptions in funding markets.

In this context, Fed measures over recent days and weeks have ranged from a total of 150 basis points of cuts to the Federal Funds Rate; the launch of open ended QE, large-scale overnight and term repurchase agreement operations; two new credit facilities to large employers; and it is also looking at a “Main Street Business Lending Programme”.

Furthermore it has also re-established a Term Asset-Backed Securities Loan Facility (TALF). Together these should help to ensure that strains in financial markets do to reach 2008-09 levels. So far, signs of stress have remained well below these; indeed, this time, it is hoped that Fed action should help support the solution to the crisis. Market strains have been evident, and as such, the Fed action looks essential in ensuring the financial sector can support the solution.

Currency markets have seen moves aplenty where the dollar has taken on safe-haven status and has been particularly well bid against commodity currencies.

One such area has been the Treasury market where volatility has been high, and despite a risk-off environment, longer-term yields moved sharply higher from record lows earlier in the month. This was not due to inflation expectations (which had fallen), but higher real yields. In common with other countries, investors seemed to be averse to duration. The Fed’s more explicit QE (now unlimited) has forced yields lower.

But speculation that the Fed could launch a Yield Curve Control policy remains. Currency markets have also seen moves aplenty where the dollar has taken on safe-haven status and has been particularly well bid against commodity currencies such as the Australian and Canadian dollars, but also notably against sterling.

We now see the Federal Funds Rate remain at its current 0-0.25% level through 2021, and other central banks also holding at new lows. As such a shift in interest rate differentials is unlikely to drive large foreign-exchange moves over the next 12 months. We eventually see US dollar strength fading back as coronavirus worries ease. We look for a euro-dollar rate of $1.10 by the end of the year, and $1.12 by the end of 2021.

Eurozone

COVID-19 infiltrated Europe, in particular Italy, just as things seemed to be settling down in China. Now, there are over 100,000 infections on the continent, with about 75% of those in the eurozone’s “core 4” economies. Northern Italy was the stem of the European outbreak. Since then, Madrid and Paris have become hotspots.

The sudden drop in economic activity as a result of coronavirus and the associated containment measures is unprecedented.

However, the infection pace has slowed somewhat, though this may be due to limited testing capacity. Because of the rapid spread, the movement of people has been acutely restricted. Lockdowns imposed across several member states, including France and Italy, have affected all sectors of the eurozone economy.

The sudden drop in economic activity as a result of coronavirus and the associated containment measures is unprecedented. March’s Composite PMI, which represents the first insight into the economic shock witnessed a 20-point fall to a record low of 31.4. In comparison, the largest monthly fall during the 2008-09 financial crisis was 4.7 points.

Judging what this means for GDP growth is challenging, but with businesses facing difficulties not seen even during 2008-09, a contraction is likely in the near term. We are pencilling in a 9% peak-to-trough fall in euro-area GDP over the first half of 2020. That leaves our 2020 forecast at -5.6%. Providing the disruption is relatively short-lived, we see a 3.5% rebound in 2021.

Market stress has also been evident, with a rise in sovereign bond yields, particularly in those countries suffering the most acute outbreaks, such as Italy, where the 10-year benchmark rate had risen 126 basis points to 2.34%. Still, yields remain way below the 7% level that raised questions marks over fiscal sustainability during the euro-area sovereign debt crisis.

However, the extent of some of the moves has once again raised some questions over fragmentation in European financial markets. We do not foresee a re-run of such fears, which raised questions over the stability of the euro area. Nonetheless, the European Central Bank will be tuned to such risks once more. However, stresses have not been limited to sovereign markets, with corporate credit markets also showing signs of strain.

Yields remain way below the 7% level that raised questions marks over fiscal sustainability during the euro-area sovereign debt crisis.

These developments in the real economy and financial markets have led to a significant ECB policy response, with the announcement of the Pandemic Emergency Purchase Programme. This constitutes an additional €750 billion of QE on top of the €120 billion announced on 12 March. This policy response has been tailored to a) stabilise financial markets, particularly in light of the surge in bond yields on 17 March, b) provide liquidity and c) ensure support for businesses.

This last point has been particularly evident through the reworked Targeted Longer-Term Refinancing Operations, which now offer banks the ability to borrow at ‑0.75% should they meet lending criteria to small and medium-sized enterprises, and the ECB’s decision to buy corporate commercial paper. But despite the extraordinary stimulus, further easing is possible and we would look for a cut in the ECB’s Deposit Rate in the second quarter.

The fiscal response has also been significant, with Italy, Germany, France and Spain announcing measures equivalent to 2% GDP on average. On top of these measures are also substantial sums of loan guarantees to support businesses facing financial problems, complementing monetary policy action. However, the euro area response has been more disjointed given the lack of a fiscal union.

Euro cross-currency basis swaps highlight the premium that has been placed on trying to access US dollar funding amidst the tightening of liquidity conditions.

But that looks set to change with moves being made to activate Europe’s bailout fund, the ESM, with the Eurogroup agreeing to offer pandemic credit lines worth 2% of each country’s GDP. A by-product of this is that it could technically open the door to the ECB’s Outright Monetary Transactions scheme (i.e. the unlimited purchase of sovereign bonds).

The idea of common euro-area bonds is also being raised, a proposal which reportedly has some support from ECB President Christine Lagarde. Against this backdrop, the euro has been under pressure, given what had been an unrelenting demand for US dollars.

Euro cross-currency basis swaps highlight the premium that has been placed on trying to access US dollar funding amidst the tightening of liquidity conditions. However, the Fed’s US dollar swap lines should alleviate some of this pressure.

Near term, we suspect that risk sentiment will continue to dominate moves with the euro-dollar exchange rate likely to trade at $1.06 in the second quarter. But on the expectation of a recovery toward the end of the year, we see fundamentals coming back into play, with our end-2020 forecast standing at $1.10.

United Kingdom

Infections in the UK have been increasing at a stark pace, but at a lower rate than some European peers. At the time of writing, there were 8,227 domestic cases of COVID-19, with 433 of those resulting in fatalities. The region most affected is London.

Prime Minister Boris Johnson has announced more restrictive containment measures to try and slow the spread. All non-essential shops have closed and citizens have been instructed to stay indoors except for food, health or critical work reasons. But social distancing efforts are taking their toll on the economy. The government and the Bank of England have been acting to try and mitigate the damage.

This initially took the form of coordinated action on the morning of the 11 March Budget. The BOE's Monetary Policy Committee cut Bank Rate by 50 basis points to 0.25%, while the Financial Policy Committee lowered the countercyclical capital buffer rate to 0%. This was then followed up by the chancellor unveiling £12 billion in dedicated COVID-19 spending. But with the situation escalating dramatically, the amount of fiscal support provided has been scaled up accordingly.

The BOE has slammed its foot on the accelerator pedal. Bank Rate has been cut to its estimated effective lower bound of 0.1%, while QE has been restarted, with a further £200 billion of gilts and corporate bonds set to be bought.

The most significant to date is a commitment to pay 80% of furloughed employees’ salaries (up to £2,500 per month) to reduce layoffs. Companies will also be able to delay VAT payments for most of the second quarter until the end of 2020-21 in a move that the Treasury estimates will provide a direct injection of £30 billion (or 1.5% of GDP).

Meanwhile, the BOE has slammed its foot on the accelerator pedal. Bank Rate has been cut to its estimated effective lower bound of 0.1%, while QE has been restarted, with a further £200 billion of gilts and corporate bonds set to be bought. Cumulatively, these actions represent around 265 basis points of conventional rate reductions. Additionally, the BOE has announced a number of initiatives to try and ensure corporates can access cheap credit.

This includes the establishment of a new Term Funding Scheme to provide business loans closer to Bank Rate, with additional incentives for extending credit to SMEs. Overall, the BOE estimates that the various measures announced will provide £100 billion in funding for businesses.

But despite the colossal scale of this stimulus, the UK economy is nevertheless set to fall into a deep recession. For one, the preliminary composite PMI slid nearly 16 points to 37.1 in March, the lowest since the series began in 1998. Also, Google searches for the term “Job Seekers Allowance” have spiked to a five-year high in a sign of widespread layoffs.

However, the peak of the downturn looks set to be the second quarter, with restrictions likely to remain in place across most (if not all) of the period and possibly tightened even further. But assuming that restrictions are eased in the summer, activity should rebound in the second half. On this basis, we look for GDP to contract 4.4% in 2020, followed by growth of 3.3% in 2021.

With much of the civil service dedicated to tackling the coronavirus, the prime minister’s plan to strike a trade agreement with the EU by the end of the year appears increasingly optimistic. The pandemic has already led to this month’s talks being cancelled, while the EU’s chief Brexit negotiator, Michel Barnier, subsequently tested positive for COVID-19.

Last week, the pound reached a low of $1.1412, a level not seen since 1985.

His British counterpart, David Frost, is also now in self-isolation after exhibiting symptoms. Therefore, it appears likely that the transition period will be extended beyond 31 December to put Brexit on the back burner. According to the Withdrawal Agreement, this can be done once for up to two years through mutual UK-EU agreement by 30 June.

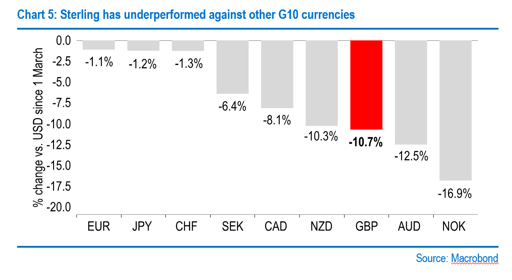

This should provide a welcome boost to sterling, which has been one of the worst-performing Group of 10 currencies amidst the recent strengthening in the greenback, with only the commodity-dependent Australian dollar and Norwegian krone faring worse. Last week, the pound reached a low of $1.1412, a level not seen since 1985. Exactly why it has underperformed relative its peers is not yet clear, but we would be surprised if Brexit was not a factor.

However, for the same reason, we believe sterling stands well-placed to benefit from a resumption in “risk-on” sentiment. Therefore, based on our expectation of a broad-based global upswing in the second half, we look for the pound to rise to $1.20 and 92 pence per euro by the end of the year.