When the national debt is owned by nationals, the interest paid and the interest earned cancels out, as do the liabilities of the taxpayers and the assets of the SA pension funds, insurance companies banks and South African citizens who have invested in SA government debt. The true burden on the SA taxpayer is the SA government debt held by foreigners.

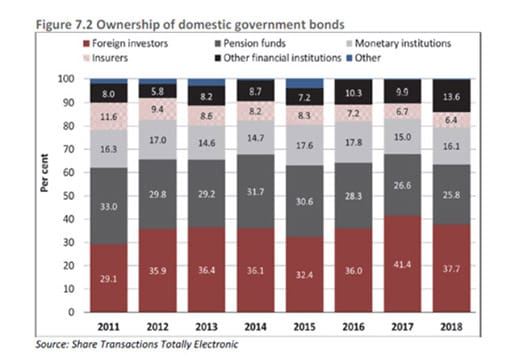

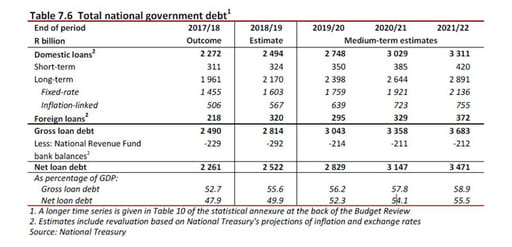

Foreign investors owned 37% of all rand-denominated debt, R923bn worth of the R2.49 trillion issued in 2018-19. They also owned all the foreign currency debt issued by the government in 2018, valued at R320bn. Thus, foreigners own about 50% of all government debt issued (see figure below, taken form the Budget Review 2019 as is the further table that provides detail on the composition of RSA national debt).

As the table above shows, there is a heavy load for South Africans to have to carry, especially when there is little to show for the debts incurred. This includes productive infrastructure that would add to GDP and incomes to be taxed and would make borrowing worthwhile, should the returns on the capital raised exceed the interest cost of the debt incurred, which has not been the case. Much of the debt incurred by the government has been used, given insufficient tax revenue, to fund the employment benefits of public-sector employees and other goods and services consumed by government agencies. In essence, it has been raising expensive debt to fund consumption rather than capital accumulation.

More sadly, some of the national debt that has been incurred and used to fund state-owned companies, mostly Eskom, has not even covered its interest rate costs. The Treasury calculates that the difference between the book value of assets of these companies (over R1.2 trillion) and their debts (over R800bn) means their equity capital earned a negative amount in 2017/18. In other words this investment by taxpayers (assets minus liabilities) is now worth nothing at all. Selling off their assets for what they could fetch in the market place would, at worst, reduce the current and future national debt burden. At best, they would provide a superior service to users of these essential services. These private companies, if profitable, could then provide an additional source of tax revenue.

What was paid for the assets is economically irrelevant. The only relevance is their market value that may or may not exceed the value of the debt incurred. Still, less national debt is better than more.

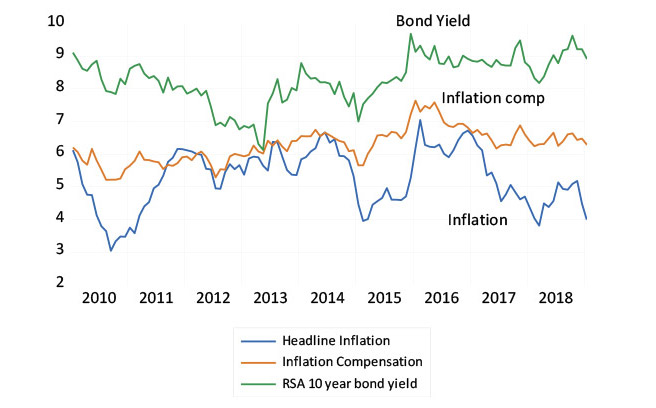

So, what can be done to reduce the burden of SA’s national debt and the dangers of a debt trap that SA has entered? One obvious answer would be for the government to borrow at lower interest rates. However, it is not lower inflation that would necessarily reduce the interest paid on conventional government debt.; only lower expected inflation could do this. Lenders demand compensation in the form of higher interest rates for taking on the risk that inflation poses to the purchasing power of their interest income and the market value of their debt. The more inflation that is expected, the higher interest rates will be.

The Governor of the Reserve Bank believes that lower inflation – the result of realising the Bank’s inflation target – will lead to lower inflation expectations and bring down interest rates with it. But the link between realised inflation and expected inflation is not nearly as direct or obvious as the recent behaviour of the bond market and interest rates confirms. In recent years, inflation compensation in the bond market, the difference in yields offered by a conventional bond exposed to the danger of unexpectedly high inflation, and an inflation-proofed bond of the same duration that offers a real yield, has remained stubbornly high. It has been at about 6%, a number that has not declined in line with lower inflation, which is currently at 4%.

Long-term interest rates, inflation compensation and inflation in SA

The problem for the Governor is that the Reserve Bank is only partially able to control the inflation rate, which is dominated by forces beyond its influence.

The exchange value of the rand, which has a large influence on inflation in SA, follows a course that is independent of Reserve Bank reactions. It is influenced by the sayings and actions of SA politicians. The rand also responds directly to global capital flows that drive the US dollar and emerging market currencies. Prices in SA respond directly to the price of imported oil and the taxes levied on it. The weather, food prices and the Eskom tariff are among other forces that always act on prices, to which the Bank can only react but not influence.

The interest rate reactions of the bank can only influence the demand side of the price equation. Reducing demand with higher interest rates, in the hope of countering the supply side shocks to prices, can depress demand in the economy.

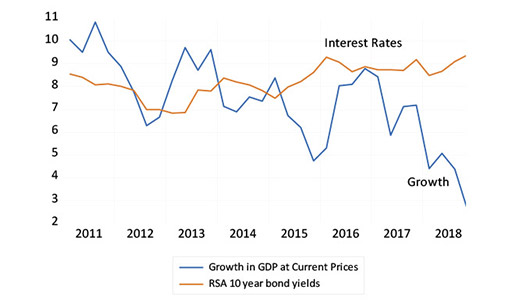

The trouble with slow growth is that it raises the risk that SA may abandon its fiscal conservatism and elect to inflate its way out of its debt, which becomes ever more burdensome with slower growth. Paradoxically perhaps, it’s a burden that also rises with lower inflation. When nominal GDP growth (real growth plus inflation) falls below interest rates, the burden of debt (debt/GDP) increases.

Long-term interest rates and growth in nominal GDP

SA can only hope to reduce the costs of funding its debt and escape the threatening debt trap by convincing the market place that it will not abandon fiscal conservatism. It will take even more than raising taxes or reducing the trajectory of government expenditure to reduce long-term interest rates meaningfully, which are both austere actions that in themselves hold back growth in the short run.

A commitment to the privatisation, rather than the reform, of our failed public enterprises is called for. This will reduce risks to lenders, bring down interest rates and permanently raise the growth rate. It will support the rand and reduce inflation by attracting additional foreign investment and capital.

Without such a change of mind and actions to back them up, the risks of us, sooner or later, inflating our way out of the debt trap will remain. Absent such reforms, our problems will continue to be exacerbated by permanently slow growth, for which the failed public enterprises will bear a large responsibility. Any failure to take this obvious action will keep up the high cost of funding borrowings.

About the author

Prof. Brian Kantor

Economist

Brian Kantor is a member of Investec's Global Investment Strategy Group. He was Head of Strategy at Investec Securities SA 2001-2008 and until recently, Head of Investment Strategy at Investec Wealth & Investment South Africa. Brian is Professor Emeritus of Economics at the University of Cape Town. He holds a B.Com and a B.A. (Hons), both from UCT.

Receive Focus insights straight to your inbox