The Quarterly Labour Force Survey released recently provides estimates of employment and unemployment that are way beyond the norm for the developed economies for which employment surveys are designed. They come as no surprise. In the fourth quarter of last year, 262,000 more jobs were provided in SA compared with the quarter before, while an additional 278,000 more workers were declared unemployed, taking the unemployment rate marginally higher to an extraordinary 35.03%. The SA labour force is estimated as 22.4 million persons, of whom 14.5 million are working and 7.9 million are actively seeking work. The labour force represents only 57% of the working age population (ages 15-65), which leaves 17 million adult South Africans economically inactive.

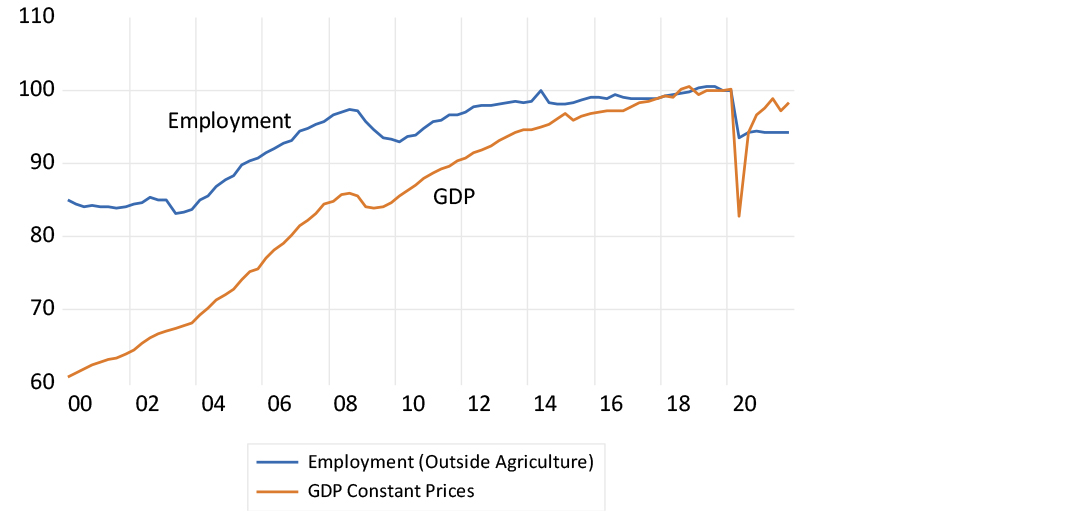

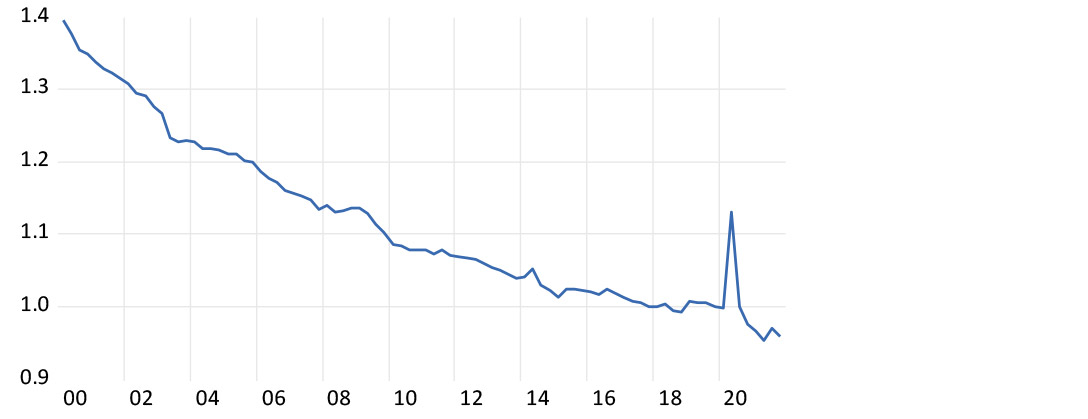

There is more to the depressed employment statistics in SA than slow growth. In 2021 there were 40% more persons employed per unit of GDP than there were in 2000. These latest estimates continue to show employment is lagging well behind GDP. Employment has flatlined at about 94% of its pre-lockdown levels. GDP by contrast fell sharply to 84% of its pre-Covid levels by Q2 2020, but has since recovered to 98.3% of its pre-Covid level.

Employment and GDP (2019 = 100)

Source: SA Reserve Bank and Investec Wealth & Investment, 31/03/2022

The ratio of employment to GDP (2019 = 1)

Source: SA Reserve Bank and Investec Wealth & Investment, 31/03/2022

How are these employment statistics, particularly the unemployment estimates, to be interpreted and reconciled with estimates of income and expenditure in SA? Part of the problem with estimating unemployment, especially where the unemployed are not simply measured when collecting unemployment benefits, is that the unemployed are largely self-defined in SA. One may be not working, yet be willing and able to work at short notice and indicate as such to a telephone enquiry from Stats SA, and so be classified as unemployed. But such a respondent (perhaps in a rural area) may only be willing to work for rewards that are unavailable and unrealistic to expect. Hence such a potential worker is not part of the labour force and more accurately should be regarded as not economically active, not as unemployed. South Africa may have an employment problem – not an unemployment problem on anything like the same scale.

The more the consumption power provided to households in kind and cash, other than via income from work, the higher will tend to be the wage that makes it sensible for potential workers to supply and accept employment. This is what economists describe as the reservation wage, below which it makes little sense to supply labour. Welfare benefits provided by the taxpayer, such as housing, medical care and cash grants, or help provided by an extended family, all help to raise the wage rates that employers have to offer when seeking a supply of workers. The tragedy is that so few South Africans qualify for the well-paid decent work offered by employers that would, if available, encourage many more of them to actively join the labour market. The excluded workers should blame the failures of the education system to qualify them for the decent work and accompanying benefits that formal employers mostly prefer to provide.

South Africa chose to address poverty with welfare rather than by encouraging employment. It was a humane response and the country was economically able to redistribute consumption power on a meaningful scale. But it has had consequences. The more generous the welfare system, the better the employment benefits that have to provided by firms seeking labour, the higher will be the level of wages and so the fewer workers employed. South Africa’s recent economic history of improved welfare and a smaller proportion of the population employed confirms this prediction. There is a negative relationship between the price of labour and the demand for it, even if it is denied by the economists (nogal) who advocate and regulate higher minimum wages.

Yet higher wages have also much encouraged the supply of and demand for immigrant labour who arrive in SA with lower reservation wages. They are also more easily hired because that can be more easily fired. The unregulated, labour-intensive sectors of the economy are heavily populated by perhaps millions of migrants. Their employment status will not be answered with a phone call. The employment problem is concentrated on South Africans with access to welfare benefits. How many are employed in South Africa remains an unknown.

About the author

Prof. Brian Kantor

Economist

Brian Kantor is a member of Investec's Global Investment Strategy Group. He was Head of Strategy at Investec Securities SA 2001-2008 and until recently, Head of Investment Strategy at Investec Wealth & Investment South Africa. Brian is Professor Emeritus of Economics at the University of Cape Town. He holds a B.Com and a B.A. (Hons), both from UCT.

Get Focus insights straight to your inbox