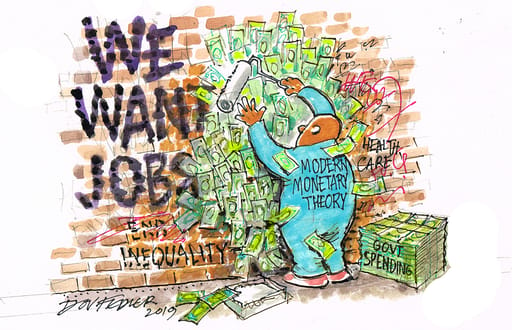

Modern monetary theory, or MMT for short, has become one of the new buzzwords in economic and policy circles.

It shouldn’t be confused with MMA (that’s mixed martial arts – also something that’s rising in popularity) or with MMR (the measles, mumps and rubella vaccine), though it certainly carries controversy, as the other two acronyms do.

Light-hearted comparisons aside, MMT is taken seriously in important circles. Could it become a mainstream policy? And what would be the consequences if it becomes widely adopted?

Before answering these questions, some definitions. There are some very technical definitions of MMT but in practice what they boil down to is this: because a country (government) controls the issue of its own currency, it shouldn’t have to worry about traditional constraints on its spending to achieve its goals.

This means a country can spend all it needs to in order to achieve its goals for employment, healthcare, and education, as well as other goals such as public infrastructure or tackling climate change. Because it prints its own currency, a country needn’t use taxation or government debt to fund its spending requirements. Importantly, proponents of MMT believe it needn’t be inflationary. But if inflation does rise, the government can then use taxation as a tool to curb spending.

Democratic candidate Bernie Sanders holds a campaign rally in Santa Monica, California, US, on July 26, 2019.

In summary MMT implies the following:

- Deficits don’t matter because the government has a monopoly on the currency;

- Hence, the government doesn’t have to worry about the extent of government debt since it can always print more cash to pay interest;

- Similarly, it doesn’t need taxation to fund its requirements;

- Taxation is there to curb inflation (which comes from overspending) or for other goals, like tackling inequality;

- Fiscal policy is the main driver of policy – monetary policy plays only a minor role.

MMT is thus something of a departure from traditional economic models, including Keynesian economics, in downplaying the role of monetary policy in achieving government’s economic goals. Notable Keynesian and Nobel Prize winner Paul Krugman is among its critics, saying it could lead to hyperinflation.

Despite these departures from traditional economic orthodoxy, MMT has gained a great deal of traction, including among US politicians on the left, such as the US’s Bernie Sanders and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez. Sanders has MMT proponents in his economic advisory team, such as Stephanie Kelton of Stony Brook University. Ocasio-Cortez has said it should be “a larger part of the conversation” about economic policy.

Arguably, MMT is a response to the way the world economy has evolved since the global financial crisis of 2008. A decade of extremely low interest rates and quantitative easing has shown the limits of monetary policy as a tool for stimulus. Growth and inflation rates remain low by historical standards among the developed economies.

Critics of tools such as quantitative easing also argue that its benefits have accrued only to the relative few, in the form of lower costs of borrowing for corporates and wealthy individuals, causing inequality levels to rise.

Arguably, this is probably why the concept has so much appeal among left-leaning politicians in the developed world.

This means that MMT is likely to feature in the political campaigns of the left in many major economies, including in the UK and US, where incumbent leaders are seen to be pro-rich. The Green New Deal proposed by Ocasio-Cortez is underpinned by MMT principles.

Republican Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez holds an immigration Town Hall in Queens on July 20, 2019 in New York City.

Not only the left

While MMT has been championed by many on the left, elements of it have found favour on the right too. President Donald Trump’s criticism of Fed policy and his willingness to use deficit spending are not a million miles away from what his opponents on the left are suggesting.

Trump’s economic adviser, Larry Kudlow, in June downplayed the significance of the US’s record national debt of US$22.5 trillion. “I don’t see this as a huge problem right now at all. It’s quite manageable,” he said in a CNBC interview.

The US budget deficit rose 40% in the first five months of this year, to a total of US$738bn (spending up by US$255bn and revenues up only US$49bn – the latter in part thanks to tax cuts implemented by the Trump administration).

Rising deficits have been a feature of the US economy for many years (Kudlow was a major critic of higher deficits during the Obama administration). Interestingly though, there has been no knock-on effect in the form of inflation. Harvard’s Marty Feldstein noted in a 2015 paper (“The inflation puzzle”, Project Syndicate, May 2015) that the relationship between the monetary base and inflation has largely broken down this century: between 2005 and 2015, the monetary base grew by 18% a year, but annual inflation averaged only 1.9%.

It’s been a similar story in other developed economies. For example, Japan, with a debt-to-GDP ratio of 240% (it’s been over 200% since the financial crisis of 2008), recorded an annual inflation rate of 0.7% in June.

More expansive fiscal policies are gaining favour in many countries. In February, Kikuo Iwata, former deputy governor of the Bank of Japan, called for a ramp-up in fiscal spending, with funding provided by the central bank. “Fiscal and monetary policies need to work as one so that more money is spent on fiscal measures and the total money going out to the economy increases as a result,” he told Reuters in an interview.

In Europe, pressure is growing on governments to loosen fiscal policy and there is likely to be a relatively small shift to more expansive policies – in response to weak growth and also to rising populist calls to reverse the austere policies of previous years.

White House National Economic Council Director Larry Kudlow is interviewed on television outside the West Wing October 05, 2018 in Washington, DC.

Pitfalls and possibilities

While the experience of deficit spending in major developed economies appears to lend some credence to some aspects of MMT, policymakers should perhaps be wary of rushing into its adaptation.

Arguably, the cases of the US and Japan are as exceptions. Since the US dollar is the world’s reserve currency, the US has considerable room to play with when it comes to its deficit. Years of quantitative easing have also helped to keep bond yields low.

However, there could be a point of no return in the future, where foreign investors will lose confidence in the US dollar and switch to a new reserve currency, such as the Chinese yuan.

In Japan’s case, most of its government debt is owned by local investors, while the demographics of an aging population are likely to keep downward pressure on prices.

It’s early days for Europe, though there does appear to be some scope for opening the purse strings further, especially in Germany. Germany’s debt to GDP ratio is below 60%, according to the European Commission, well below Italy’s 130%, France’s 100% and the 90% for the Eurozone as a whole. A boost in infrastructure spending, which Germany now appears to be warming to, could be a boost for the country as well as the region.

For emerging economies, the case is less convincing. Hyperinflation in countries like Venezuela show the dangers of fiscal profligacy, especially for smaller countries that are heavily exposed to changes in demand for commodities or that borrow heavily in other currencies.

In SA’s case, MMT would be a bold experiment, especially given our exposure to foreign capital flows. Government’s recent announcement of further funding for Eskom – an extra R59bn over two years – was not well received by the rating agencies nor by the currency markets. Given the fiscal constraints caused by Eskom and other state-owned entities, there appears to be little scope for government to implement MMT anyway.

The case against – and a way forward?

Apart from the argument that MMT remains an experiment that is still in its early days, critics of it highlight what they regard as an overreliance on fiscal policy – and by implication the ability of governments to spend wisely – to achieve development and growth goals.

MMT, as we have noted, downplays central banks as role players in guiding policy. Central banks have the advantage, in most key economies, of being able to set interest rates and adopt asset purchasing programmes without government interference and so are an important check and balance against government.

Would governments, conscious of the need to get re-elected, be willing to introduce unpopular taxes as a remedy to rising inflation? This is an important question to ask of both developed and emerging market economies. Moreover, governments may not have much room to invest in growth and development initiatives. In the US for example, an increasingly larger proportion of state spending is in non-discretionary areas (such as mandatory healthcare or retirement benefits).

The discretionary portion of expenditure has fallen from 65% of Federal spending 50 years ago, to about 30% today, according to the US Congressional Budget Office.

Given these concerns, perhaps the answer lies in broadening the argument to include central banks as role players. Ray Dalio, author, and co-chairman of Bridgewater advocates what he calls “monetary policy 3” (or MP3). Given the limits of interest rate policy (MP1) and quantitative easing (MP2), the coordination of monetary and fiscal policy (MP3) could be the answer, with monetary policy directed more at spenders than savers and investors (where MP1 and MP2 are aimed).

It’s still early days in both the MMT and Dalio’s MP3 debates. As with many other policy debates, we will probably only know the answers much further down the line.

About the author

Patrick Lawlor

Editor

Patrick writes and edits content for Investec Wealth & Investment, and Corporate and Institutional Banking, including editing the Daily View, Monthly View, and One Magazine - an online publication for Investec's Wealth clients. Patrick was a financial journalist for many years for publications such as Financial Mail, Finweek, and Business Report. He holds a BA and a PDM (Bus.Admin.) both from Wits University.

Receive Focus insights straight to your inbox