The last year has seen an increase in the number and value of corporate deals, both locally and internationally. Like their global peers, listed JSE companies have been busy, either acquiring companies, selling off businesses or being the targets of acquisitions.

In principle, this trend should be good news for minority shareholders. Merger and acquisition (M&A) activity allows businesses to build scale, diversify and vertically integrate, thus increasing shareholder value. Selling off non-core assets on the other hand, allows them to focus on their core strengths; while the sale of the full business or a de-listing can often realise value for minority shareholders through a cash offer.

It’s this last category we’ll be focusing on in this article. A company will de-list for a number of possible reasons. It may receive an attractive offer from another company – listed, unlisted or foreign. Or the management and key shareholders may decide that a listing no longer suits its needs and offers to buy out minority shareholders for cash (management and key shareholders will either raise the cash to do so themselves or work in partnership with an external investor, such as a private equity firm, to do so).

The big question for minority shareholders is whether they get a good deal out of a delisting or takeover. The worry for minorities is that management or the founding shareholders, with a good feel for the fundamentals of the business and the business cycle, may make an offer that underrepresents the true value of the business. Accepting such a cash offer thus represents an opportunity cost for investors if they cannot participate in the upside. Alternatively, minorities could end up with shares in an unlisted business and have little to no say in how it is run and without the ability to sell the shares at a market-related price.

The worry for minorities is that management or the founding shareholders, with a good feel for the fundamentals of the business and the business cycle, may make an offer that underrepresents the true value of the business.

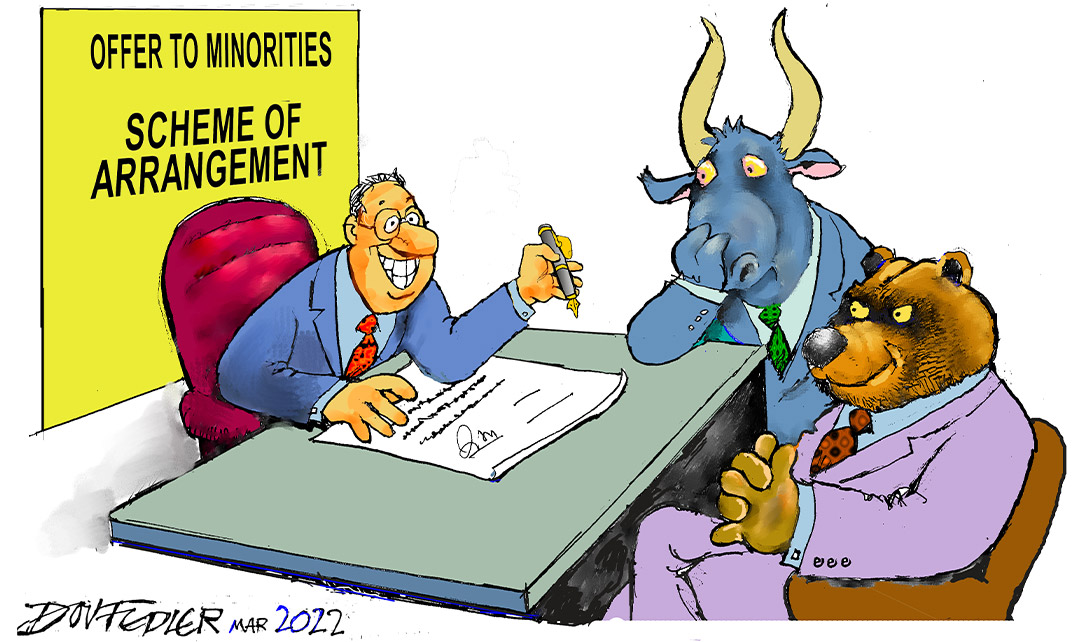

South African law provides some protection for minorities. Typically, the sale or delisting of a business will go through a process called a scheme of arrangement – an agreement between shareholders to accept a certain offer price. Not all shareholders have to agree to such a scheme, but at least 75% of shareholders (other than the offeror) will have to agree to the terms for a scheme to be passed.

South African law also requires what is known as a “fair and reasonable” assessment of the offer by an impartial outsider, usually a specialist not connected to those making the offer. Shareholders can then vote based on their own assessments of the true value of the offer, with the “fair and reasonable” report as a guideline.

But what happens when you, as a minority shareholder, do not agree with the price offered and are unable to persuade other minority shareholders of your view? South African company law provides a remedy in the form of what is known as an appraisal right.

Barry Shamley, portfolio manager at Investec Wealth & Investment, explains that appraisal rights were introduced into South African law in 2008, through section 164 of the Companies Act, as a mechanism to protect minorities.

“An appraisal right is a legal right of shareholders to demand a judicial proceeding or independent valuation of the company's shares, with the goal of determining a fair value of the share price in cases of an acquisition or delisting,” he says.

In practice, appraisal rights are triggered whenever a resolution is proposed in certain circumstances, including: the disposal of all or greater part of the company’s assets, amalgamations or mergers and schemes of arrangement. “The rights will also be triggered if the company wants to amend its Memorandum of Incorporation by altering the preferences, rights, limitations or any other terms of any class of shares in a manner materially adverse to the rights or interests of holders of that class of shares,” adds Shamley.

To exercise the appraisal rights, a shareholder needs to make a written objection ahead of the meeting to vote on the resolution. Furthermore, the shareholder needs to vote against the resolution.

Should the resolution nonetheless be passed, the dissenting shareholder then has 20 days to exercise their rights, by way of a written notice demanding the payment of fair value for the shares. The offeror / company is then obliged to pay the dissenting shareholder the fair value for the shares (note that there is no free rider situation when it comes to appraisal rights – non-dissenting shareholders are not entitled to the improved price).

What constitutes fair value is the crux of the issue. The company must respond with what it regards as fair value and how it has come up with that particular value. If there is a fair and reasonable assessment, it can always use that as its basis for the value originally paid.

At this point, Shamley explains, the dissenting shareholder has the option of going to the courts, provided of course it can argue the case for a higher valuation.

“This is a risky and potentially expensive course of action,” says Shamley. “The costs of going to court could possibly exceed the extra value you might be able to attain from the company making the offer.”

The reality however is that the company itself will often be wary of an expensive legal process and the poor publicity that could arise out of this.

“In one particular situation where we pursued our appraisal rights as portfolio managers, we were able to get the company to offer to buy the shares at a meaningful premium above the midpoint of the range suggested in the fair and reasonable assessment,” says Shamley.

Appraisal rights are an important aspect of investor protection, says Jacquie Howard, head of legal at Investec Wealth & Investment.

“In a takeover, our clients may find that they are minorities. The fair value mechanism that appraisal rights provide can be an effective legal tool to balance the power between our clients on the one hand and the controlling shareholders and management on the other hand,” she says. “This increased power for our clients assists in ensuring that they have an avenue which legally compels the company to justify the price that has been offered and, possibly, to offer a higher price.”

The benefits of having an active manager

To exercise appraisal rights is not a simple task for a minority shareholder. It requires knowledge of section 164 of the Companies Act, in particular of the procedures for exercising ahead of a resolution. Missing one of the steps, such as notifying the company ahead of a vote, can derail the process. Investors should also remember to vote through the correct entity (eg the correct nominee company, if shares are held this way).

Minority investors will also need to do their homework to come up with a compelling reason for a higher valuation. And finally, going to court can be an expensive process.

That’s where the value of an active manager comes in, says Shamley. “An active manager, acting on behalf of its investors, by definition carefully analyses the companies it invests in, both prior to investing and on an ongoing basis. An active manager should be able to assess whether an offer price is fair or not,” he argues. “An active manager also has access to legal advice, if it chooses to pursue an appraisal right in the courts.”

Importantly, shares Shamley, the active manager should be closely aligned with maximising value for its clients, while also having a strong commitment to governance. “Investors in a fund will take their cue on what’s fair value or not from the approach or policy of the portfolio manager. Investors should always be prepared to ask questions of their portfolio manager about the willingness to extract the greatest shareholder value in these circumstances.

Appraisal rights checklist:

- What is an appraisal right? An appraisal right is a legal right of a company's shareholders to demand a judicial proceeding or independent valuation of the company's shares with the goal of determining a fair value of the stock price.

- When is it triggered? Appraisal rights are normally triggered when there is a notice to shareholders by the company of a meeting to consider adopting a resolution to enter into a transaction contemplated in inter alia s112 of the Companies Act. These include: the disposal of all or greater part of the company’s assets, amalgamations or mergers and schemes of arrangement.

What is the process?

- Before the meeting the shareholder must submit a written notice to the company objecting to the resolution.

- The shareholder must ensure that its shares are voted against the adoption of the applicable resolution.

- If the resolution is subsequently passed, the company must let the dissenting shareholder know that the resolution has been passed, within 10 business days.

- The dissenting shareholder then has 20 business days to exercise the appraisal rights, namely to demand in writing that the company repurchase the shares at fair value (a copy of the demand must be sent to the Takeover Regulation Panel).

- The company must then submit an offer to the dissenting shareholder within five business days, at the amount considered fair value, along with a statement about how the value was determined.

About the author

Patrick Lawlor

Editor

Patrick writes and edits content for Investec Wealth & Investment, and Corporate and Institutional Banking, including editing the Daily View, Monthly View, and One Magazine - an online publication for Investec's Wealth clients. Patrick was a financial journalist for many years for publications such as Financial Mail, Finweek, and Business Report. He holds a BA and a PDM (Bus.Admin.) both from Wits University.

Receive Focus insights straight to your inbox