Politics and economics in South Africa have always been intertwined with the mining industry. Since the discoveries in the 19th century of diamonds near Kimberley and gold on the Witwatersrand, mining has not only been South Africa’s most important industry, but also perhaps its most contentious one politically. Race relations and the tensions between labour, business and government have been themes almost from the start.

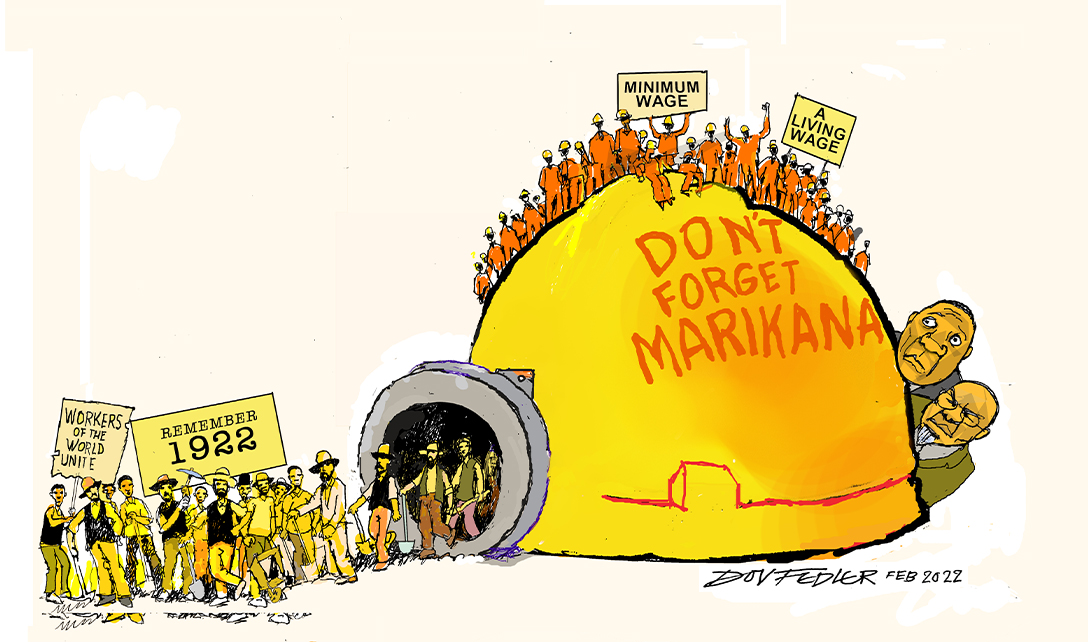

Confrontational labour relations perhaps reached their peak in the 1980s when organised labour was one of the few legal ways to organise and protest against the apartheid system. But the tensions between labour, business and government have not gone away in the almost three decades since the end of apartheid and will need to be tackled if the country’s growth and equality challenges are to be met.

In this article, we look back at events of 100 and 10 years ago, their impact on the South Africa of today and discuss what the future holds.

The 1922 Rand Revolt

The Rand Revolt broke out in March 1922, and while it was quelled fairly quickly, it had long lasting effects on the politics as well as the economy of the country – much of which we are still grappling with today.

The 1922 uprising of white mine workers was a culmination of a number of previous strikes in the previous years over pay and working conditions. Following the discovery of gold on the Witwatersrand in 1886, the major mining companies had recruited a number of British mineworkers experienced in the coal mining industries back home. After the Anglo Boer War, this workforce was increasingly supplemented by Afrikaner miners and black labourers from the rural areas.

The increasingly deep-level nature of the gold mines posed challenges and great physical risk for workers. The delineation between black and white labour was also established at a very early stage, with the skilled and semi-skilled positions being reserved for white workers and black workers being allocated to unskilled positions.

Tensions over race, pay, safety and conditions developed from an early stage. Marxist ideals were also taking hold among the world’s working classes at the time. The British immigrant miners, many of whom had participated in the major strikes that took place in Britain in the early 20th century, brought their ideas and union experience with them to South Africa. However, these same workers were also staunchly in favour of the colour bar, which ensured better scales of pay for white miners.

In this the socialist, English speaking miners (who predominantly supported South Africa’s Labour Party, established in 1909) found some common ground with the Afrikaner miners, who predominantly supported the National Party.

The mine owners, the so-called “Rand lords” who had profited so handsomely through the early decades of the discovery of the world’s largest gold deposits, were keen to find ways to reduce costs. This was especially so with falls in the gold price after World War 1. Cheap labour was essential to maintaining profitability.

Making changes to the colour bar (the forerunner to apartheid), seemed an obvious choice. White workers made up 10% of the 200,000 strong workforce on the mines after World War 1; yet the wage bill for whites was double that for blacks.

White workers made up 10% of the 200,000 strong workforce on the mines after World War 1; yet the wage bill for whites was double that for blacks.

In 1921, the Chamber of Mines proposed a number of changes, whereby thousands of semi-skilled and unskilled white miners would be dismissed and the colour bar be partially lifted to allow black miners to fill these positions (at lower wages).

The reaction of the white workers was an angry one. Supported by the opposition National Party and the Labour Party, a series of strikes took place, culminating in a general strike in March 1922. They marched under the banner “Workers of the world unite for a white South Africa”, while the more militant white miners organised commandos and created fortifications in the main Witwatersrand towns like Johannesburg, Benoni, Brakpan and Springs. Numerous bloody exchanges took place, including indiscriminate attacks on black miners and the police.

The government, headed by Prime Minister Jan Smuts, responded with the full force of the armed forces: infantry, artillery and bomber aircraft. The rebellion was quickly crushed, resulting in the deaths of over 200 people, injuries to over 1,000 and 4,748 arrests.

Just as the Afrikaner and English-speaking white mineworkers found common ground in taking up the cudgels against the mine owners, so the government’s response was driven by a confluence of interests and threats. Smuts’ South African Party was a merger of Afrikaner and English members, driven by a desire to forge a new (white) South African identity for the then young Union of South Africa, as a leading member of the British Commonwealth. Smuts and his predecessor Louis Botha (who died in 1919 of complications linked to the Spanish flu) had led South Africa into World War 1 on the side of Britain, an unpopular decision for many Afrikaners, who still harboured resentment towards Britain and remembered Germany’s support of the Boer republics in the Anglo Boer War.

Smuts was also acutely aware of the importance of gold to the fledgling economy and so was inclined to support the mine bosses. In the background, the Russian Revolution of 1917 and the rise of the Soviet Union made many leaders in the western world, Smuts included, particularly wary of communism and of workers’ movements in general.

In the end, Smuts succeeded in putting down the rebellion, though it cost him in the ballots of 1924. A coalition of the National Party and the Labour Party won that election, and wasted little time in implementing mining labour laws that were to be the blueprint for labour relations for several decades. Indeed, many of today’s problems can be traced back to the changes implemented then.

The rather Orwellian sounding “civilised labour policy” entrenched the colour bar, reserving skilled and semi-skilled positions for whites. While it brought peace to the mining sector, it set the scene for the increasing segregation that was to follow, culminating in the National Party election victory in 1948 and the strict apartheid policies that followed.

We can speculate about how history might have changed had the coalition not won the 1924 election. Would there have been a gradual breakdown in racial segregation and the worst excesses of apartheid avoided? Or would the hardline segregationists have succeeded eventually anyway? We will never know.

What is clear is that the pay and working conditions in the mining sector (and notably in the deep level mining), overlaid with apartheid policies, continued to be sources of tension and conflict, particularly in the later years of apartheid. As noted above however, these tensions did not disappear after the end of apartheid.

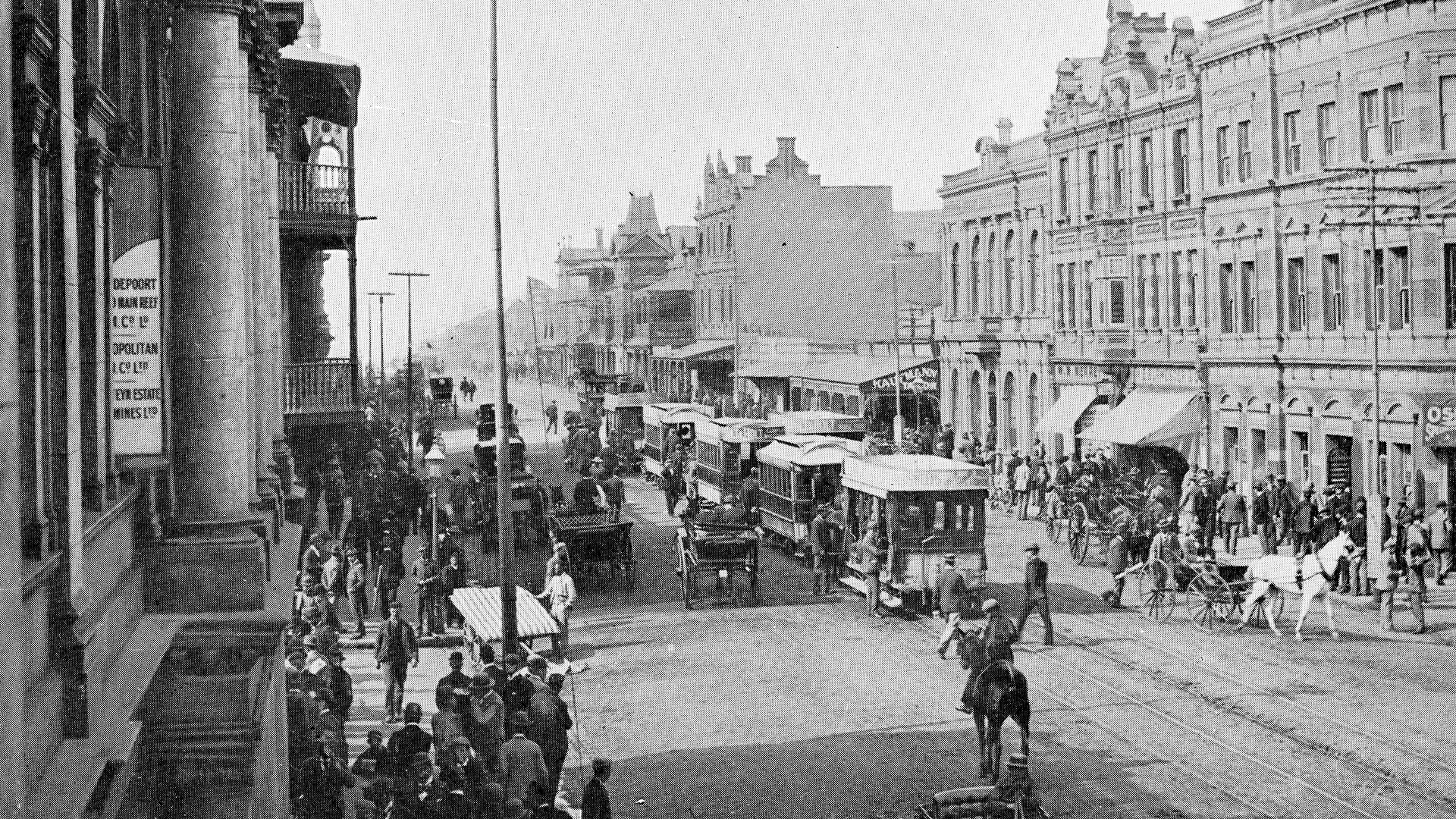

Commissioner Street, Johannesburg – the city of Johannesburg grew rapidly after the discovery of gold on the Witwatersrand in 1886

Marikana 2012

There have been numerous flashpoints between organised labour and business in almost the three decades since full democracy arrived in South Africa, particularly in the mining and related industries. Of all of these however, what happened on 16 August 2012 at Lonmin’s Marikana mine is the one that stands out in the memory.

In early August 2012, a number of rock-drillers in the platinum belt launched a wildcat strike, demanding a tripling of wages, in part to compensate them for the dangerous nature of their work. Violence and tension marked the next few weeks, with the situation perhaps stoked by tensions between the ANC-aligned National Union of Mineworkers (NUM) and its emerging rival, the Association of Mineworkers and Construction Union (Amcu).

This violence led to a number of deaths of miners, security personnel and policemen, so that when striking miners and police faced each other on the afternoon of 16 August at the Marikana mine (which today is owned by Sibanye-Stillwater), tensions were already running high.

There are different accounts about what triggered the decision by police to open fire, a decision that led to the deaths of 34 miners and the wounding of at least 78 others. These were presented at the subsequent Farlam Commission, which investigated the massacre.

Protests and strikes followed the massacre, with most workers at Marikana refusing to return to work for several days after the massacre. Lonmin reported major losses in production, while several other mining groups were also affected. The industry was also affected by major strikes in the following years, such as in 2014, when it was estimated that the platinum mining industry lost about 1.2 million ounces in production.

The aftermath of Marikana

Despite all of the above, Marikana appears to not have had the crippling impact on the mining sector that might have been expected. Unlike the Rand Revolt, the Marikana massacre did not lead to a change in government or any major legislative changes. And the mining industry appeared to be able to negotiate the following years reasonably well. A 2015 paper by Nicholas Hill and Warren Maroun of the School of Accountancy at the University of the Witwatersrand, notes that “the Marikana incident does not appear to have had a widespread and prolonged effect on the South African mining sector. This may be the result of the strike action already having been discounted into the price of mining shares, implying that the market was only reacting to the unusually violent (but short-lived) protest. Alternately, the results could be indicative of investor confidence in the corporate social responsibility initiatives of the South African mining industry as a whole”.

Employment in the mining sector however did fall in the years following Marikana, from around 500,000 in 2012 to about 450,000 in 2016. However it has remained around that level since then, with even the lockdowns of 2020 having a minimal impact. According to the Minerals Council Facts and Figures Report for 2020: “The impact of the production disruptions on employment levels seems not to have had a material impact. The full year 2020 employee numbers are 452,866, which is 9,172 jobs less than the average during 2019, or 2% lower. However, compensation for employees increased by 5% in the same year.”

Indeed, the last two years have been good for mining, with higher commodity prices lifting a range of metals, including iron ore, gold, manganese and chrome. This has translated into higher exports, record trade balances and improved tax revenues for the fiscus, thanks to the profitability of the mining sector.

Mining has also become safer. While fatality numbers can vary from year to year, the trend lines are unmistakably pointing in a downward direction. According to the Minerals Council Facts and Figures Report for 2020, 60 fatalities were recorded that year and while this was up from 51 in 2019, it is well down on the 309 deaths reported in 1999 and the 112 reported in 2012. Figures for injuries show a similar pattern.

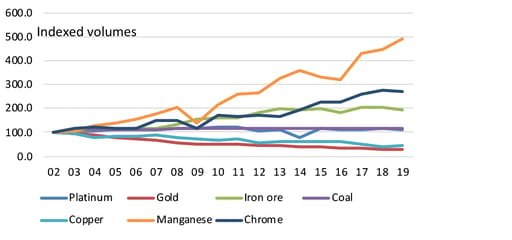

While the prices of gold, platinum and iron ore have certainly helped to lift the economy in the last two years, it’s the likes of manganese and chrome that appear to be carrying the baton

Cometh the hour, cometh the metal

It’s worth noting that South Africa has had the good fortune of being able to produce important minerals in abundance at key stages in its history. Gold production received a boost with the development of the Free State gold fields after World War 2. Platinum, though first discovered in the Bushveld igneous complex soon after the 1922 events, came into its own after the development of autocatalyst technologies in the 1970s. The platinum industry was able to ramp up production just as gold output started to wane.

While the prices of gold, platinum and iron ore have certainly helped to lift the economy in the last two years, it’s the likes of manganese and chrome that appear to be carrying the baton, as the chart below shows. Manganese has a broad range of uses, including steel production, dry cell batteries and alloys, while chrome is used in electroplating, tanning and dyeing, and as an anti-corrosive, among other uses.

South Africa – indexed production levels

Source: Bloomberg, Investec Wealth & Investment, January 2020

However the drive to create a greener future should also provide a boost for other metals that South Africa produces. To achieve the global net zero emissions goals, the world will need to produce a lot more copper and nickel for example, for use in renewable energy power applications and electric vehicles, for example. Platinum, nickel and chrome are also used in hydrogen fuel cells.

What the future holds

While the future may look bright for South Africa’s leading metals, it’s important to acknowledge the challenges that remain. Investment is sorely needed in transport and power infrastructure to ensure demand can be met. South Africa also needs to invest in safer and less energy-intensive forms of production, in order to access deep-lying reserves without incurring prohibitive costs. Many mines use robots – which require only a narrow stope and do not need clean, cool air to operate – and their usage will certainly grow in the coming years.

What is clear is that, even with the right investment, the mining industry cannot be expected to do the heavy lifting when it comes to tackling high rates of unemployment. The biggest investment of all may need to be in human capital, in building the skills that will help grow the services and technological sectors. Hopefully a vibrant mining sector can provide at least some of the capital to make that investment.

Further reading:

White on white violence: The 1922 Rand Revolution, Rodney Warwick, Politicsweb, 15 March 2012

Tracing the 1922 Strike, SJ de Klerk, The Heritage Portal, 14 July 2019

Assessing the potential impact of the Marikana incident on South African mining companies: An event method study, Nicholas Hill and Warren Maroun, University of the Witwatersrand, 2015

Minerals Council Facts and Figures Report for 2020

About the author

Patrick Lawlor

Editor

Patrick writes and edits content for Investec Wealth & Investment, and Corporate and Institutional Banking, including editing the Daily View, Monthly View, and One Magazine - an online publication for Investec's Wealth clients. Patrick was a financial journalist for many years for publications such as Financial Mail, Finweek, and Business Report. He holds a BA and a PDM (Bus.Admin.) both from Wits University.

Receive Focus insights straight to your inbox