I asked my mother recently what financial risk meant to her and her answer was simple: running out of money. As someone who belongs to that broad group we call financial advisers, I often think we complicate things with concepts like volatility, correlation and ratios when, at the heart of it all, clients just want to know that they won't run out of money.

Now all of those things are important in constructing a portfolio that achieves this simple objective, but they could be communicated more clearly. I will try to do so by using an example.

Scenario 1: 65-year-old living to 85

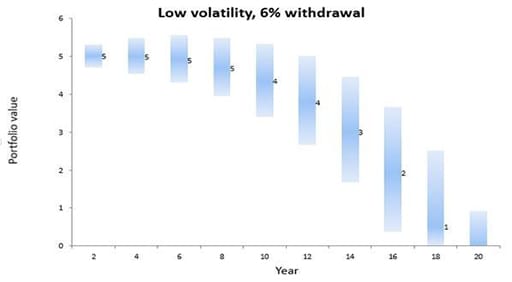

I played a "when will I run out of money" game by projecting some scenarios with an imaginary client who is 65 (close to my mum's age) and will, in all likelihood, live until at least 85. Simplistically, the client has R5m and requires at least R300 000 a year in income from this capital.

Being prudent and assuming they have some income from elsewhere, I have used an income tax rate of 25%. Inflation is assumed to be 6% a year and the income has been adjusted for it, year-on-year. Let's assume this is a low-risk client or someone who doesn't like volatility, such as my mum.

Accordingly, the money is invested in a low-equity, high-cash portfolio with a volatility measure (standard deviation) of 5.9%. So, when will the client "run out of money"?

Given the above assumptions and projecting 10 000 scenarios, their return profiles are illustrated below. The bars represent a distribution of wealth outcomes. The lighter top of the bars is the 75th percentile of distributions; the bottom lighter part, the 25th percentile; and the darker middle, the 50th percentile.

In the example below, the lower percentile of scenarios suggests that they could run out of money after 18 years. The mean of scenarios suggests it is more probable that they could deplete their funds in 19 years – which is okay, not brilliant, but they should limp through to 85 (they will be in trouble if they live longer).

Source: Investec Wealth & Investment

If your measure of risk is running out of money, volatility or short-term fluctuations are not more risky but actually less risky. However, the risk lies in not being able to ride through the troughs.

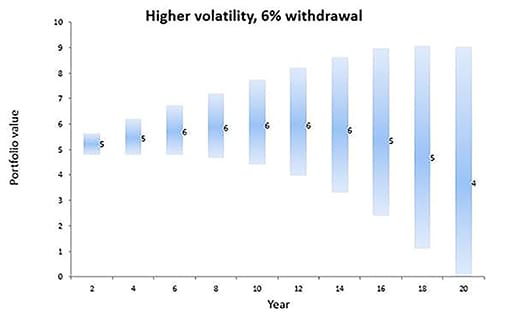

Increasing the equity component and adding offshore investments increases the volatility measure to 8.61% and changes the outcomes, as set out below; the mean "running out of money" scenario has been pushed out considerably, past 20 years.

Source: Investec Wealth & Investment and Bloomberg

They now should get to 85 and beyond with a bigger cushion. So, if your measure of risk is running out of money, volatility or short-term fluctuations are not more risky but actually less risky. However, the risk lies in not being able to ride through the troughs. These scenarios assume that the client stays invested and doesn't switch out when things get uncomfortable.

The client in these scenarios is, however, drawing an income, and that presents a challenge because one doesn't want to draw into a downturn, which crystalises losses. Since the client would be drawing a fixed amount, the percentage draw would increase as a proportion of the investment total if the value of their investments fell in a market drawdown.

One could reduce this risk by drawing a percentage of the total investment value rather than a fixed monthly amount. But in reality, this is impractical as one has fixed expenses. Another way of reducing this risk is to build in downside protection by setting up 'buckets' within the portfolio and including cash reserves for living expenses.

I read a good article on this recently from Charles Schwab. The writer, Rob Williams, proposes setting aside 12 months' worth of expenses in a liquid cash account and a further two to four years' worth of expenses in short-term bonds, or bond funds, in case there is a market downturn.

With this cushion, the writer explains, one is less likely to have to sell more volatile investments at a loss. On average, over the past 50 years, it took the S&P 500 about three years to recover from each downturn.

READ MORE: Timing vs time in the market

Another way to reduce the risk of running out of money is to reduce tax leakage by looking at the total return. While the client in this scenario has a low income tax rate, there is still a great difference between 25% income tax and capital gains tax (CGT) of 10%. By creating a cash/near cash 'moat' to prevent dipping into the equity at depressed levels, the client can then invest the bulk of the savings in investments, which attract CGT rather than income tax, thus enhancing the after-tax return.

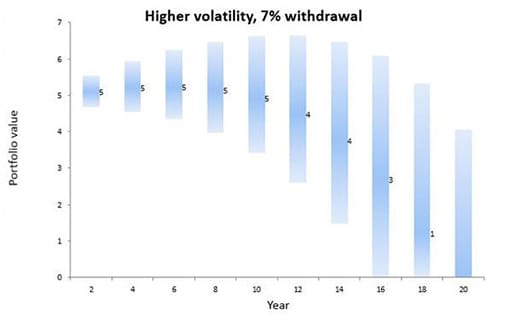

Scenario 2: Increased drawing

Most obviously, the fastest way to run out of money is to spend it. I ran another scenario where the drawing was increased to 7%, or R350 000 a year. In the original low-volatility scenario, increasing the drawing by 1% to 7% took two years off the time of the mean scenario of when they could run out of money and brought the lower percentile of possible scenarios forward to 14 years.

Source: Investec Wealth & Investment and Bloomberg

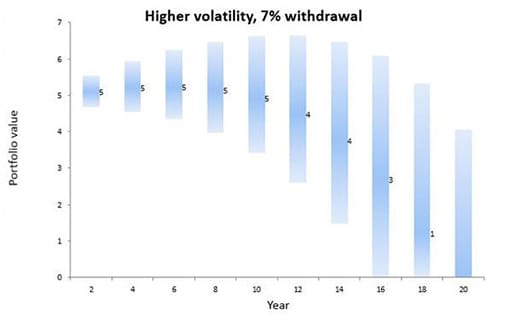

Interestingly, the higher volatility portfolio actually bought or afforded the client the higher draw.

Source: Investec Wealth & Investment and Bloomberg

So, perhaps we need to relook at risk, which isn't, in my view, volatility or short-term market downturns (as illustrated, they are the friend of the long-term investor) but rather, as my mother so clearly put it, running out of money.

Receive Focus insights straight to your inbox