In any functional financial system, trust is the single most important intangible asset and serves as the backbone of a banking system. Fatefully, the Latin origin of “credit”, “credere” has the meaning “to believe” (“to trust in the truth”). Trust establishes confidence. Once customer trust is broken, banks become extraordinarily vulnerable. Unfortunately, the public perception of banks remains tainted, with the public view still tilted towards the “banks are greedy and exploitative” end of the spectrum.

The outcomes of recent rapid-fire events (SVB and Signature Bank failures; the resolution of the issues at First Republic Bank and acquisition of the bulk of its operations by JPMorgan; and UBS acquiring Credit Suisse) demonstrate what a break in trust looks like in the age of the internet. The significant increase in internet usage, coupled with the proliferation of social media platforms has provided fertile ground for digital herd behaviour. The speed at which information travels across social media platforms together with the digitalisation of banking has fuelled the speed of depositor actions.

In short, we had two consecutive bank bail-out weekends on two different continents in March. Such an occurrence has the smell of a banking crisis.

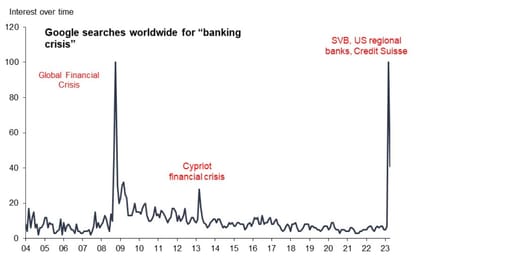

Unfortunately, during periods of financial (and emotional) stress, we tend to draw false analogies to historical events whose features do not resemble the current context. A good example of this is how internet search patterns change during times of stress. Google search intensity, a proxy for what dominates the mindshare of the investor and consumer over time, shows that the topic of “banking crisis” hasn’t been this talked about since the Global Financial Crisis (GFC).

Source: Google Trends / Investec Wealth & Investment

Date sampled: 20/04/2023

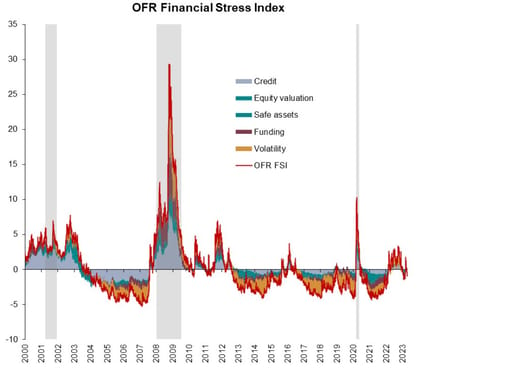

But a look at the Office of Financial Research (OFR) Financial Stress Index, gives a different story. The index reveals that numerous measures of financial market stress are far from the levels associated with either recessions or financial crises.

Source: Office of Financial Research / Investec Wealth & Investment

Recession bands in grey

Date sampled: 21/04/2023

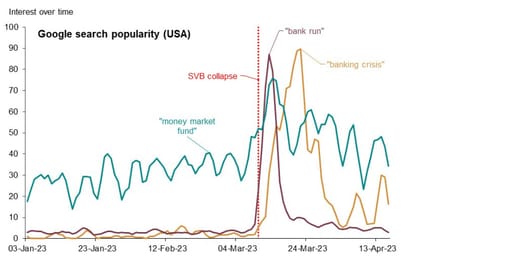

And interest has waned in the weeks since the last bank failure. Seemingly, the view that poor risk management in a handful of regional US banks could destabilise the global financial system is losing steam, particularly in the US.

Source: Google Trends / Investec Wealth & Investment

Date sampled: 20/04/2023

Could this be the calm before the storm (GFC 2.0) or is it contained to the proverbial teacup? To answer that question, we need to define what we mean by a banking crisis.

Defining a banking crisis

There is an extensive body of work done by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) (Systemic Banking Crises Revisited) and the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) (Booms and banking crises) which examines whether the episodes of the past few months share key features with crisis events in the past. Ultimately, the litmus test is predicated on two conditions:

- Significant signs of financial distress in the banking system (as indicated by significant bank runs, losses in the banking system, and/or bank liquidations).

- Significant banking policy intervention measures in response to significant losses in the banking system.

When it comes to the first condition, small banks had a sizeable deposit outflow in the week immediately after SVB, but those outflows ended thereafter, according to the most recent data. Large banks are seeing steady deposit outflows, but these predate SVB and started mid-2022 when the Fed began hiking interest rates in earnest. These deposit outflows should therefore be considered a natural consequence of Fed tightening and not a reflection of SVB. Even after their declines over the past month, the level of US bank deposits is still higher than the pre-Covid trend would imply.

On the second condition, estimates by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) and other banking statistics tell an interesting story.

Firstly, the FDIC estimates that, for SVB and signature bank combined, the cost to its Deposit Insurance Fund is approximately $23bn (about 0.09% of US nominal GDP). This is well below the direct outlays related to the restructuring of the US financial sector during the GFC, which represented 4.5% of nominal GDP.

Secondly, combined deposits of the failed banks, guaranteed by the FDIC, represented a meagre 1.5% or thereabouts of total banking sector deposits and 1% of nominal GDP. To put this in context, JPMorgan represents 11% of total banking sector deposits and about 7.4% of nominal GDP, highlighting its systemic importance to the US economy.

Thirdly, the liquidity provided by the Federal Reserve through the existing discount window and newly formed Bank Term Funding Programme (BFTP) in the weeks following the collapse of SVB and Signature represented about 1.6% of total banking sector funding, meaningfully lower than the 4.7% peak in liquidity provided during the GFC.

Lastly, the fall of SVB and Signature Bank did not spur deposit freezes, bank holidays, or the nationalisation of any of the systemically important, “Big 4” banks (Citigroup, Bank of America, Wells Fargo, JPMorgan).

The events of the last month did cause a meaningful disturbance in the global banking sector. But they are a far cry from the GFC when considered in the context of the post-GFC regulatory reforms that have been put in place to safeguard the financial system.

Are there any risks on the horizon?

Monetary policy famously works with long and variable lags, and we should expect tighter monetary policy to now start impacting economic data negatively. But it’s important to consider the starting position as we head into a period of macroeconomic strain. A notable feature of the current macroeconomic backdrop is the deleveraging of the key economies that were at the epicentre of the GFC, namely the US, UK, and Eurozone. Setting aside the impact of Covid-19 disturbances in the data, private sector credit as a share of GDP has been stable, with notable declines in household sector leverage in the UK and US since the GFC.

How should regulators react?

Investor and depositor anxiety is understandably elevated and while we believe the regulators have the right tools (developed post-GFC) to arrest the present banking emergency, these tools need to be recalibrated to take the speed of the internet into account. Michael Barr, Vice Chair for Supervision at the Federal Reserve, was clear in his testimony to the US Senate Committee that current supervisory approaches would be adjusted to better respond to a rapidly changing banking environment.

He noted: “Recent events have shown that we must evolve our understanding of banking in light of changing technologies and emerging risks. To that end, we are analysing what recent events have taught us about banking, customer behaviour, social media, concentrated and novel business models, rapid growth, deposit runs, interest rate risk, and other factors, and we are considering the implications for how we should be regulating and supervising our financial institutions. And for how we think about financial stability.”

In summary – what this means for the banking sector

The inevitable outcome, to restore trust and rebuild confidence in the banking system, will be a further tweaking of regulations. At the same time, events like these spur meaningful changes in depositor behaviour. While it’s early days, we suspect that:

- Banks will have to move quickly to increase deposit rates to restore the risk/reward views of depositors.

- Borrowing costs for corporates and individuals will rise to protect margins and account for the asset quality risks that are emerging in the face of the increased volatility in the system and economy.

- The harsh reminder of the tail risks associated with investing in banks will drive a higher cost-of-equity for the sector and banks’ borrowing costs are likely to rise for a period, placing further pressure on margins.

- Costs to comply will inevitably rise, reducing profit margins.

All of this will place pressure on bank profitability over the short to medium term. Because marginal players cannot operate under this sort of pressure, this environment will also spur further consolidation in the sector.

About the author

Kevin Harding

Research Analyst, Investec Wealth & Investment

Kevin is currently focused on enhancing the coverage of global financial services firms, seeking out high-quality developed market stocks suitable for our funds and discretionary portfolios. He previously worked at Investec Securities as an equity research analyst, with primary coverage of Sub-Saharan (ex-SA) African banks and supporting coverage on South African banks. Prior to joining Investec, Kevin was a senior manager in PwC’s Financial Services Risk and Regulation consulting practice in South Africa. Kevin holds a CA (SA) and completed his articles at PwC South Africa in the Banking and Capital Markets division.

Receive Focus insights straight to your inbox

Disclaimer

Although information has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable, Investec Wealth & Investment International (Pty) Ltd or its affiliates and/or subsidiaries (collectively “W&I”) does not warrant its completeness or accuracy. Opinions and estimates represent W&I’s view at the time of going to print and are subject to change without notice. Investments in general and, derivatives, in particular, involve numerous risks, including, among others, market risk, counterparty default risk and liquidity risk. The information contained herein is for information purposes only and readers should not rely on such information as advice in relation to a specific issue without taking financial, banking, investment or other professional advice. W&I and/or its employees may hold a position in any securities or financial instruments mentioned herein. The information contained in this document does not constitute an offer or solicitation of investment, financial or banking services by W&I . W&I accepts no liability for any loss or damage of whatsoever nature including, but not limited to, loss of profits, goodwill or any type of financial or other pecuniary or direct or special indirect or consequential loss howsoever arising whether in negligence or for breach of contract or other duty as a result of use of the or reliance on the information contained in this document, whether authorised or not. W&I does not make representation that the information provided is appropriate for use in all jurisdictions or by all investors or other potential clients who are therefore responsible for compliance with their applicable local laws and regulations. This document may not be reproduced in whole or in part or copies circulated without the prior written consent of W&I.

Investec Wealth & Investment International (Pty) Ltd, registration number 1972/008905/07. A member of the JSE Equity, Equity Derivatives, Currency Derivatives, Bond Derivatives and Interest Rate Derivatives Markets. An authorised financial services provider, license number 15886. A registered credit provider, registration number NCRCP262.