What is long-term investing?

It’s been a tough old time to be an investor in South African growth assets. Delivering above-inflation returns has been difficult in both the short and medium-term. Because of this, across the industry, investors are de-risking their portfolios by moving money out of medium-risk funds into low-risk options – a potentially big mistake in my opinion, but perhaps the subject of another article.

If you look at market performances, it should not be surprising that investors are de-risking their portfolios. Over the most recent five-, three- and one-year periods, domestic equity and property failed to keep pace with inflation. Of the growth asset classes, only global equities delivered the expected return. In fact, the more exposure a fund had to domestic growth assets, the weaker the historic return. The 10-year returns, however, look more “normal” and reasonable over this period.

The above prompted me to think about what it means to be a long-term investor or simply put: just how long is the long-term?

“But this long run is a misleading guide to current affairs. In the long run we are all dead.”

John Maynard Keynes

For some people, “long-term investment” means holding on for five to 10 years. For others, it’s committing to a stock or fund forever, and there’s never a right time to sell. The reality, of course, is that there are plenty of situations when getting out of a long-term investment is exactly the right decision so that you can put that money to work someplace else.

Monitoring and reviewing your positions are part of the process. But you must consider who is making the sell recommendation. For a commission-driven broker in the business of selling transactions, moving money around is how he or she makes his or her living. A good adviser does the opposite and helps you remain calm to keep you on course, especially when there’s drama.

Long-term investing is about thinking ahead and planning how to have enough money for the rest of your life.

Say no to gambling

Firstly, let me explain what long term investing isn’t. It’s not what you see on Jim Cramer’s TV show, Mad Money, which involves a one-man show focused on erratic buying and selling and is more about entertainment than serious investing. No, long-term investing is about thinking ahead and planning how to have enough money for the rest of your life.

It’s about how to diversify your serious investments, it’s not reacting with urgency, or trying to get lucky and make a few quick bucks. There’s a big difference between urgent and important. Planning for something as meaningful and long-term as how you’ll live out the last 30 years of your life may not be urgent today, but most would agree it is very important.

Enjoy the ride

The historical record is clear: time and again, studies reveal long-term returns vastly outperform short-term returns. It doesn’t matter which investments we’re talking about: equities, bonds, and property are always a better investment when you take the long view.

That said, I’m not suggesting that investing long-term means not touching your positions. Pruning (selling or adjusting) your portfolio is part of a successful long-term approach, such as when you need to re-balance your portfolio to stay within your guidelines, free up capital, or if you’ve met your investment targets.

So, what does long-term mean?

While it’s true that putting your money on the line is never easy, the historical record of the stock market is virtually irrefutable: US markets have consistently performed over long holding periods, going back to the 19th century.

Market performance (1872-2018)

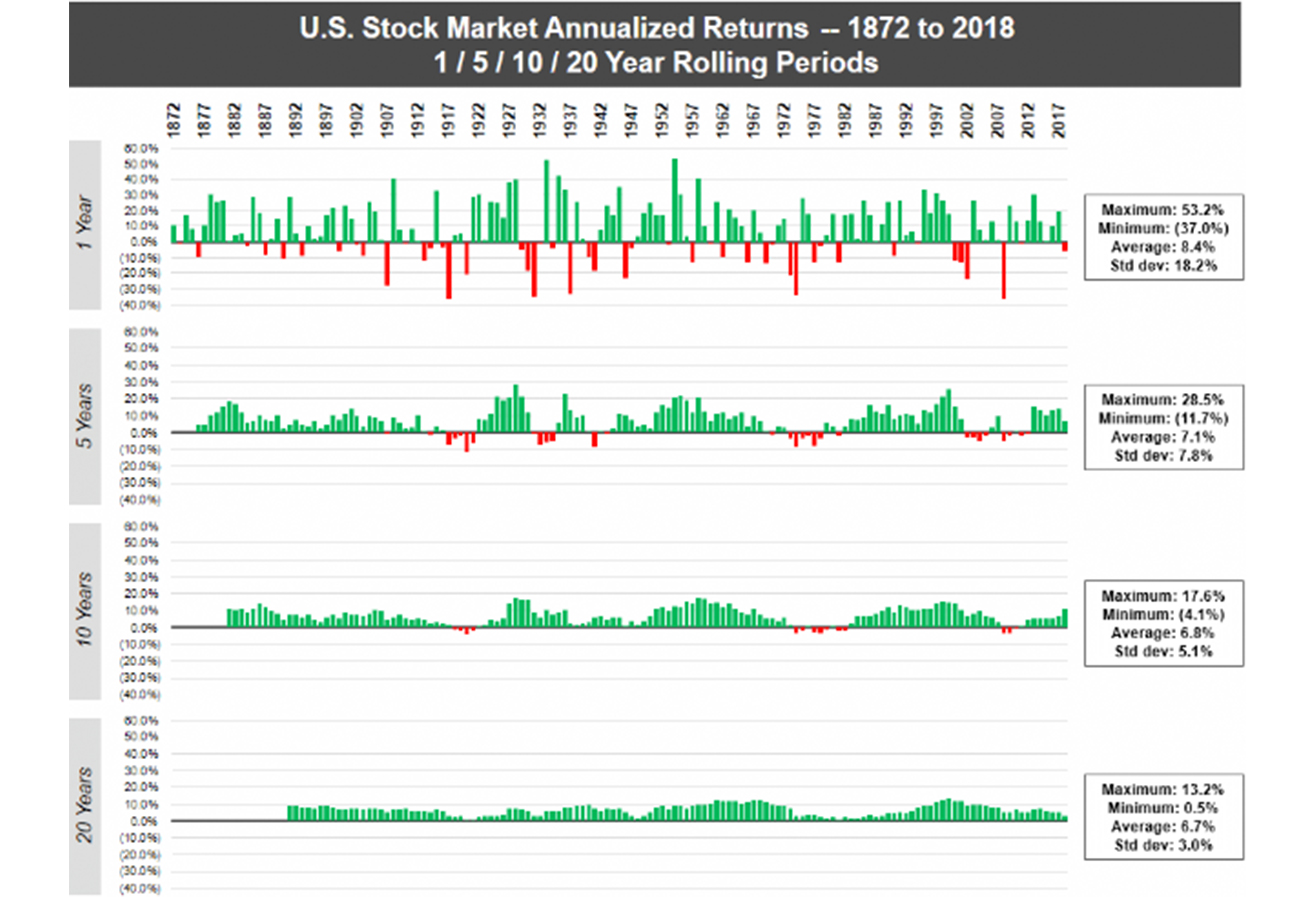

The chart below comes from a financial website called “The Measure of a Plan”, which provides tools for personal financial planning. A post on this website shows the performance of the US market over different rolling time horizons, using annualised returns.

Note: The chart uses real total returns from the S&P Composite Index from 1872 to 1957, and then the S&P 500 Index from 1957 onwards. Data has been adjusted for reinvestment of dividends as well as inflation. The data set is released and managed by US economist and Nobel Laureate Robert Shiller.

Data reflects real total returns (i.e. including the re-investment of dividends and adjusted for inflation)

Using just one-year intervals, the market can be a crapshoot. Unfortunately, if you were to just choose a one-year period at random, there would be a significant chance of losing money.

However, as the timeframes get longer, the frequency of losses rapidly decreases. By the time you get to the 20-year windows, there isn’t a single instance in which the market had a negative return.

Why time matters

Over 146 years of data, the chance of seeing negative returns for any given year is about 31%.

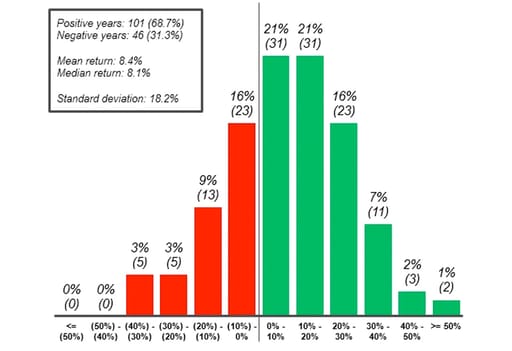

That fact is quite alarming, but the important thing to note is the distribution of returns in those down years. As the following chart (also from “The Measure of a Plan”) shows, it’s not uncommon for a down year to skew in the high negatives, just as it did during the crisis of 2008:

Distribution of 1yr Total Real Returns

According to the data, there have been 10 individual years where the market has lost upwards of 20% – and while those off years are greatly outnumbered by the years with positive returns, it makes it clear that timeframe matters.

Past performance obviously doesn’t guarantee future results, but the historical track record, in this case, is quite robust.

Long-term investors can see that if their time horizon is measured in the decades, you can take the odds of making money in the stock market to the bank.

The question then becomes, how much of your total investment portfolio do you want to commit for 20+ years? You’ll be far more likely to stick it out if you allocate only a certain portion of your savings long term, and you’re more likely to be successful investing in smaller amounts consistently over those longer time periods. Unless, of course, you can devote hours to researching every individual company and then accurately pinpoint when to buy low and sell high.

Beware of quarterly results

It’s very easy to be misled if you’re evaluating your portfolio’s results on a quarter-to-quarter basis. Again, this can create that false sense of urgency and prompt premature, knee-jerk decisions. Emotional investing destroys retirement dreams, and costs inexperienced investors a ridiculous amount of money over their lifetimes. Even the pros get caught up in the game. Making drastic investment changes based exclusively from quarterly results is a downright dangerous approach, and the inevitable outcome is that your risks will significantly increase.

Speaking of volatility

There’s no way of getting around the fact that investing has become more volatile and unpredictable, and that motion can make you seasick and derail even the most solid plan. Diversification wins all battles and ultimately, investing by its definition means you’re putting your skin in the game, which implies you’re going to have the patience and discipline to let those investments earn the greatest possible returns, even with the ups and downs.

Final thoughts

If you’re looking to make a quick buck by jumping in and out of the market, quite often you’ll find yourself on the losing end of things. Over short time periods, there’s no telling if the market will go up, down, or sideways.

However, if you have the patience and fortitude to hold onto your investments for 10 or 20+ years, your prospects become much brighter. You’ll ride out the short-term noise and benefit from the long-term upward trend. While this is often easier said than done, your wealth manager can help remove the emotion from investing, so that you can navigate together through any short or medium-term pain.

As always, Warren Buffett put it best:

“The stock market is a device for transferring money from the impatient to the patient”.

About the author

Patrick Duggan

Wealth manager: Investec Wealth & Investment

Patrick is a senior private client wealth manager with Investec Wealth & Investment, specialising in providing holistic investment planning advice to some of South Africa’s high net worth and ultra-high net worth individuals, families and their associated entities.

Receive Focus insights straight to your inbox