Get Focus insights straight to your inbox

The compounding growth of the West is powered by business enterprises and savers share in the wealth created.

The economic history of Western economies is an admirable one. Their standard of living has been transformed over the past 200 years by consistently positive year-by-year growth in output and in incomes per head, despite the rapid growth in population over the same period. And all of this was achieved despite the destruction of life and capital, buildings and valuable infrastructure by periodic wars. The Russian war in Ukraine is an awful reminder of how destructive war is. It will take many years of sacrificing consumption – of saving and productive investment in capital equipment and infrastructure – to make up for these losses.

Privately owned businesses are responsible for much of the growth in incomes earned, and in the extra goods and services supplied to the western economies over time. Their most decisive stakeholder is the consumer of this growing cornucopia of goods and services that they produce. Their owners earn a surplus after all contracted-for costs of production have been met and revenues have been collected. There is the risk of a loss, though a growing economy makes losses less likely. More efficient businesses will also compete on the prices for and quality of goods and services they provide their customers, at the possible expense of the revenue line. Improvements in the productivity of capital will be widely shared.

A stock exchange enables the ownership rights in larger businesses to be widely and conveniently shared and traded. It provides the average saver the opportunity to plug into these surpluses and the wealth-creating machine of immense force that is business enterprise, mostly via their pension and mutual funds. These widely dispersed owners have realised much more wealth creation than they would have done by investing their savings in the money market, bank deposits or in the bonds and bills issued by governments. And they would have done even better had they further postponed consumption and reinvested the dividend income they received, as well as conserving their capital gains by staying in the stock market.

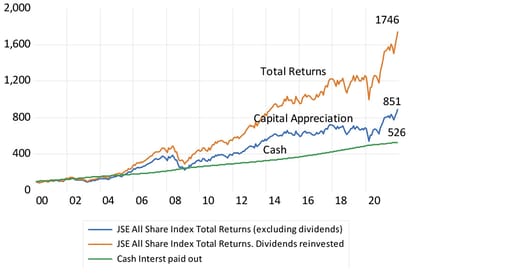

The JSE, very much part of a global capital market, has provided comparably excellent returns over the many years of its existence and has repeated the performance this century. As illustrated below, the average annual total returns with dividends reinvested from the JSE since 2000 have been nearly twice as high as the interest earned on cash and paid out: 13.5% annually vs 7.6% annually. The compounding effect has been so powerful because the returns on extra capital invested by privately owned businesses have been so positive. Economists therefore go further, given past performance. They regard these high expected returns over the long run, as part of the cost of capital employed. They add these higher expected returns to the returns that should be required of any company contemplating an investment decision. It is called the (expected) equity risk premium. If the proposed project cannot promise to leap over this higher hurdle of required returns on capital, the advice is not to go ahead.

JSE All Share Index, with or without reinvesting dividends, and money market returns (three-month Johannesburg Inter Bank Rate) (2000 = 100)

Source: Iress, Bloomberg and Investec Wealth & Investment, 9 May 2022

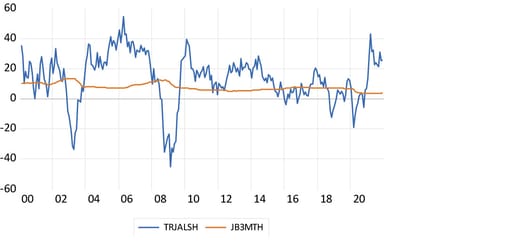

JSE All Share Index total returns vs cash (three-month Johannesburg Inter Bank Rate) 2000 to 2021

Source; Iress, Bloomberg and Investec Wealth & Investment, 9 May 2022

It is not only returns that matter – so does risk. Human nature says (expected) return and estimates of risk are positively related.

So, the obvious conclusion would seem to be to invest in the stock market, since, based on past experience it can be expected to perform well in the long-term, even if there are some short-term blips. It is these short-term blips however that discourage investment in the share market. Between 2000 and 2021 the annual total return on the JSE was 13.5% a year and that provided by the money market was a much less 7.6% a year return on average. However judged by the movement about this average return, the JSE was nearly seven times as risky, as measured by the standard deviation about these returns (see figure above) – the risk that your shares may be worth much less in a few days or months, when you might be forced by circumstances to liquidate your wealth. This can be a major deterrent to share ownership.

The greater the risk aversion, the less comfort wealth owners and potential share owners have in the outlook for assets, the less time they wish to spend in the stock market, the less valuable businesses become. And the greater will be the risk premium earned by those willing and able to stay in the stock market. Bearing extra risk will likely bring extra returns because the entry price to the share market is reduced by the risk aversion of other potential investors. It has been true of the share market over the long run and market volatility, or risk, is likely to continue to negatively influence the long-term value of shares, so improving realised rates of return for those with an extended time in the market.

Albert Einstein famously described the power of compounding interest or returns as the “eighth wonder of the world,” saying, “He who understands it, earns it; he who doesn't, pays for it.” This powerful force of low-digit exponential growth, of growth compounding on growth, year on year, is well demonstrated by the long-term ability of the major stock exchanges to grow wealth for shareholders in a consistent way over the same long run.

It is the return on owners’ capital that is the source of all interest income

But where do these good compounding share market returns come from? From businesses who are entrusted with much of the accumulated savings or wealth, described as capital employed in any market-led economy. The owners and managers of businesses are incentivised to husband scarce capital, as best they know how. The rate of return they realise on the capital employed, the productivity of that capital, is the foundation upon which all rewards from saving and owning capital or wealth is built. Firms experiment continuously in improving the return on the capital they utilise. They aim to improve the relationship between the cash value of the resources they invest in, called operating costs and what comes out as revenues, and they apply their fixed and working capital to the purpose. The results of such efforts are measured, hopefully in a consistent and comparative way, as return on capital employed inside the firm. The rewards for savers who supply the firms with capital to invest, come not only in the form of dividends paid, but in offers of interest payments that firms are able and willing to make to attract capital, in competition with other firms for the same potentially productive capital.

The less risky interest income offered by all other borrowers, the banks and the government, is therefore strongly influenced by the same return on capital realised by the business enterprise that employs a large proportion of the capital available. The banks, the money market funds, or the government as a borrower, would not offer the interest they do, unless the firms were able to earn a positive rate of return on all the capital they utilise and have to compete for. This includes competing for the overdrafts and mortgage loans provided by banks and other financial intermediaries. The higher the expected real returns from all the capital employed in businesses, the more competition from firms for additional capital to invest, the larger will be the real rewards for all saving. Be it named interest or dividends or lease payments or capital gains depending on the financial arrangements agreed to between suppliers and raisers of capital.

The internal return on capital is what is converted into market value and market returns

It is the positive internal rates of return on capital realised by the business enterprise, not share market returns, that reveals the productivity of the capital it employs. The share market in turn translates expected internal returns on capital into current share market values. The market value of the firm should be understood as the present value of future operating or cash surpluses over operating costs, expected from the firm, discounted by the required returns expected from likely alternative investments. The most valuable firms in the market-place – measured as the ratio of its current market valuation to current earnings or better current cash flows – are those firms that are expected to consistently improve their internal returns on capital and to add more capital by doing so. In other words, they are expected to consistently improve the productivity of capital they utilise and are able and willing to attract more capital, both loan and equity capital, to realise the growth opportunity, and to successfully hold the competition at bay that always threatens prices and operating margins.

The two measures of performance (the internal and market returns) are likely to be highly correlated over the long run. But such present value calculations made by the buyers and sellers of shares in companies are subject to considerable uncertainty from day to day and week to week or quarter to quarter. There is uncertainty about flows of revenue, operating costs and returns from alternative investments that determine the discount rate. There are more than enough unknowns to make estimating the future value of a firm or a market of them, a risky business. Risky returns help to direct savings to the lower return, less risky alternatives, for example to cash or cash like assets.

Knowledge (technology) improves the productivity of capital. Will it continue to do so, and will shareholders receive as valuable a share of the surplus generated?

The force that has driven the extraordinary and consistently unpredicted improvements in income and wealth and in the supply of goods and services delivered, is the success of technology and its application by the business organisation in sustaining and improving the (internal) return on capital, year by year and decade by decade. From railroads to electricity to the motor car, computers and the internet, technology has provided the opportunity to improve returns on capital and increase incomes and wealth, of which a large part is held in the form of shares of companies. A further explanation for consistently good returns to capital over time is perhaps that technology has consistently delivered more than most investors thought technology would deliver over the last two centuries. Stock markets have done so well because the productivity improvements from innovative technology have been at least what the market hoped they might deliver, and consistently delivered at least the productivity enhancements that it is expected to deliver, and typically considerably more. We have had few technology disappointments and technology has overwhelmingly surprised on the upside.

Will technology continue to consistently surprise on the upside in future and benefit the owners of the representative business enterprise and its customers and employees (and government treasuries) in the same way it has done over the last 200 years? There are some caveats.

Productivity has been dramatically driven by improving and ever cheaper computer power. Moore’s law, which predicts that computer power per dollar invested in a chip will increase at an exponential rate, has been shown to be approximately true for around 50 years. But such increases in the power of computer chips must necessarily face physical limitations because of the finite nature of matter.

Similarly, can one assume that the efficiency of food production will continue to improve at the rates it has in the past? The finite resources of planet earth may put a brake on the pace of technological improvement (unless we extend ourselves by settling the planets and beyond, and investing in knowledge itself may defeat the law of diminishing returns). Moreover, will humanity attach as much importance to increasing further our command over goods and services through productive capital expenditure as much as we have in the past and tolerate the share of output going to owners of capital as we have in the past? Capital and its application may be given a lower priority and if so, growth rates will subside.

This article was co-authored by Graham Barr, Emeritus Professor of Statistics at the University of Cape Town

About the author

Prof. Brian Kantor

Economist

Brian Kantor is a member of Investec's Global Investment Strategy Group. He was Head of Strategy at Investec Securities SA 2001-2008 and until recently, Head of Investment Strategy at Investec Wealth & Investment South Africa. Brian is Professor Emeritus of Economics at the University of Cape Town. He holds a B.Com and a B.A. (Hons), both from UCT.

Get Focus insights straight to your inbox