When is a Budget not a Budget?

Chancellor of the Exchequer Rishi Sunak is set to publish the UK government's Spring Forecast Statement on Wednesday next week. In practice, this is a renamed (and retimed) version of the previous Autumn Statement, given the general rescheduling of budgets towards the end of each calendar year. Despite the new packaging, its title is probably misleading. While the Budget is of course the major vehicle for announcing fiscal changes, chancellors can and do announce new policies outside formal Budget exercises. In September, the government announced a 1.25 percentage point hike in National Insurance Contributions to fund social care commitments. Last month, it introduced a package of measures intended to cushion households from the 54% increase in the energy price cap taking effect in April. In 2020, the year was peppered with numerous policy changes due to the Covid-19 pandemic. The Institute for Fiscal Studies estimated there were a total of 15 major fiscal events in the year following the start of the pandemic.

Once again, household energy bills are a major area of concern. Russia's invasion of Ukraine has put further pressure on global energy prices and although oil and gas prices have eased back over the past week or so, the energy price cap is still on course to rise sharply again in October. Investec's utilities team recently suggested the increase could be in the region of a further 50%. Mitigating the cost of consumers' energy bills would be expensive. The chancellor is reported to have pushed back against these requests, doubtless to protect the UK's fiscal position, perhaps ahead of planned reductions in taxation for the next election, due by December 2024. This might mean that Sunak announces specific revenue-raising measures, to fund or part-fund any relief package. A 'windfall' levy on oil and gas producing companies would be one possibility. Another would be to do nothing for now and to defer a decision until later in the year.

The broader question though is whether there is room for a giveaway. The chancellor has introduced a new set of fiscal rules, in the shape of a new Fiscal Charter. This is set out via a fiscal mandate:

- To have public sector net debt excluding the Bank of England as a percentage of GDP falling by the third year of the rolling forecast period.

In addition there are three supplementary targets:

- To balance the current budget by the third year of the rolling forecast period.

- To ensure that public sector net investment does not exceed three per cent of GDP on average over the rolling five-year forecast period.

- To ensure that expenditure on welfare is contained within a predetermined cap and margin set by the Treasury.

The charter also includes a wider group of metrics which will be assessed in fiscal policy decisions. The first concerns debt affordability indicators, which will include 'sensitivity to changes in the economic outlook, as well as wider risks such as the share of debt held overseas'. The second is a broader set of balance sheet data e.g. 'public sector net financial liabilities and net worth, alongside the debt measure that is targeted in the fiscal mandate'. Lastly, the government has the authority to suspend temporarily the fiscal mandate and supplementary targets should there be a significant, negative shock to the economy.

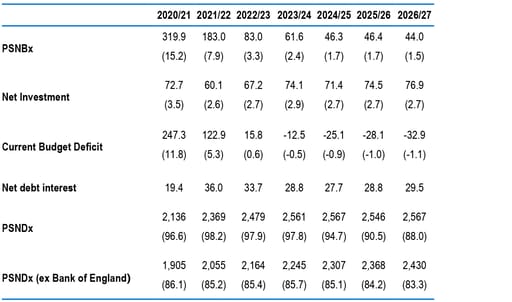

In the October Budget, the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) concluded that each of the rules in the proposed charter was met – although Parliament had not yet approved this. The fiscal mandate itself was forecast to be fulfilled with a margin of £17.5bn. Subsequently, published figures on the public finances have shown that the deficit is closing faster than the OBR expected in October. This is principally on the back of the strength of the labour market and firm spending in the economy boosting revenues. Moreover, government expenditure on social benefits is relatively subdued. Overall, 10 months of data for the fiscal year have been published so far, with February's numbers due on Tuesday. From this, it looks as though public sector net borrowing excluding public sector banks (PSNBx) for the year will be somewhere between £150bn-£160bn, rather than the OBR's Budget forecast of £183bn. Moreover, other metrics such as net debt are also improving faster than expected.

It does seem incongruous to be talking about the room for fiscal easing measures when the level of borrowing is so high (some 6.5% of GDP). Moreover, it could be argued that the faster pace of improvement is partly due to an earlier tightening in the labour market than expected, effectively only 'borrowing' the improvement from later years. Even so, Sunak probably does have the option to state that a package of new measures is consistent with meeting his new fiscal rules.

Table 1: OBR Autumn 2021 fiscal forecasts*, £bn (figures in brackets are % of GDP)

*2020/21 estimates are outturns, not forecasts

Source: Office for Budget Responsibility

Responding to the cost of living crisis will be the key priority

The key issue the chancellor will have to grapple with is what has been termed the ‘cost-of-living crisis’. At the time of the latest Budget (in October 2021), Consumer Price Index (CPI) inflation was projected to average 4.0% in 2022, already well above the Bank of England’s 2% target. This forecast is certain to be revised up substantially this time. In its latest projections published in February’s Monetary Policy Report, the Bank of England revealed the Monetary Policy Committee was anticipating an average inflation rate of 5.75% this year. Since then, the outbreak of war in Ukraine has exacerbated price pressures within the UK. An important part of that, although by no means all of it, has been the surge in natural gas prices on wholesale markets. This stands to not only raise gas bills, but also electricity prices, because gas is the key marginal fuel used in power generation.

The issue of surging utility bills is not new. Indeed, it was clear already in late 2021 that household bills would see a substantial jump when the utility price cap for households was next reset, in April 2022. In the event, Ofgem settled on a rise of 54% that will take effect next month, which will cost households around £20bn in aggregate. Mindful of this, Chancellor Sunak had sought to soften the blow, announcing on the same day as Ofgem’s decision a universal zero-interest loan of £200 per household, repayable over five years, to be applied to consumer bills from October, as well as grants of £150 for around four fifths of consumers through council tax rebates, to take effect already in April 2022. However, the cost of this to taxpayers and the benefit households receive may be considerably less than the £9.1bn price tag suggested by the government. That is because the loan element of the package is repayable over time.

As a result of the outbreak of war in Ukraine, however, the package put forward by Chancellor Sunak in February – which in any case had been only a partial mitigation – looks increasingly inadequate. It is still early days in calculating how gas price movements now could affect the utility cap come the October reset, and the volatility in prices is enormous. A ‘mark-to-market’ ballpark figure put forward by our utilities analysts suggests, however, that there could be another rise of 50% or so. That alone would add over £27bn to household bills this year. And of course, households are not the only ones feeling the pain: companies across the country are facing higher energy bills too, mitigated only to the extent they could, and did, hedge against this. On top of that, the war has put steep upward pressure on food and other commodity prices on global wholesale markets, and risks prolonging supply chain disruptions that had fuelled price pressures over the past year. The pressure is undoubtedly on for the chancellor to put more help on the table for households – and perhaps extend this to certain firms also.

A ‘mark-to-market’ ballpark figure on the utility cap put forward by our utilities analysts suggests that there could be another rise of 50% or so. That alone would add over £27bn to household bills this year.

To offer support, a number of options are available to the chancellor. One possibility is to cut taxes – or, more realistically in this case, to delay the rise in National Insurance contributions that are planned for April 2022, soon to be rebranded as the new Health and Social Care Levy. Although a blunt instrument, and only helping those in employment, this would have the advantage of benefitting both firms and their staff. There have been numerous calls for doing so already; Sir Charlie Bean, until recently a senior official at the OBR and prior to that Deputy Governor at the Bank of England, added his voice to this, calling a one-year delay in this plan ‘no problem’. However unfortunate the timing of this planned fiscal tightening is in the context of the Ukrainian war, Chancellor Sunak has so far strongly pushed back on such calls. Indeed, it has also been argued that it may be difficult in practice to delay this hike with relatively short notice: the next tax year starts on 6 April.

A further tax measure that has been suggested is for a cut in fuel tax. This would, again, benefit certain households and firms more than others, while bypassing those unable to afford running a car – who may be the hardest hit by the inflation surge. It may also prove difficult to reverse in future, as well as running counter to some climate change targets. But it certainly is an option.

On the expenditure side, the chancellor could simply scale up his planned utility loan scheme and council tax rebate – and perhaps, to make it more generous, switch some of the planned loan to a grant after all. This could potentially be more targeted towards lower-income households. A similar scheme could perhaps also be introduced for smaller companies. Alternatively, the chancellor could look at ways to uprate state benefits more generously, as these are decided on the basis of past inflation (in this case, September 2021’s 3.1%, as per the CPI – the ‘triple lock’ that would have seen a rise in line with earnings growth is currently suspended), recipients of such benefits stand to take a particularly large hit to their real incomes otherwise. That, however, could be a costly move – directly, and because it would strengthen calls for larger public sector wage rises as well.

As regards funding these or other measures of support (or indeed to pay for additional defence spending linked to the war in Ukraine), in addition to using the ‘fiscal space’ outlined above, Sunak could turn to imposing a windfall tax on oil and gas producers in the UK, who have seen profits rise strongly due to soaring global energy prices. This could be a risky move, at a time when not only domestic oil and gas production is crucial in the context of near-term energy security, but it is also paramount not to discourage renewable energy suppliers from entering the market. Politically, however, it is by no means unprecedented – not even for Conservative chancellors: Geoffrey Howe imposed just that on North Sea oil and gas producers in November 1980, as did George Osborne in 2011.

Economic forecasts – in a better place to face downside risks

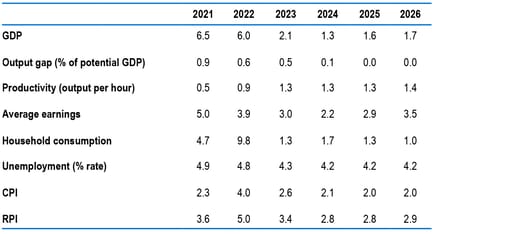

Another tumultuous period for the economy means that the OBR’s macroeconomic forecasts are due for another overhaul, especially the nearer term numbers. Recall that at the Autumn Budget the OBR used gross domestic product (GDP) numbers from before the Blue Book revisions at the chancellor’s request, which understated output for the first half of 2021. More favourable revisions since then and a slightly stronger-than-expected second half of the year means that UK GDP saw growth of 7.5% in 2021, exceeding the OBR’s forecast of 6.5%. A stronger 2021 reduces the scope for ‘excess growth’ in 2022, and is combined with several headwinds in the form of: persistent inflation; monetary tightening; fiscal tightening; a potential drag on global growth in the wake of war in Ukraine; and an extra public holiday for the Queen’s Platinum Jubilee. OBR expectations for 2022 output are therefore likely to see a significant downgrade from +6.0% currently. Our own forecast for GDP growth this year is +4.4%, a 0.2 percentage point upgrade to our previous expectation given the larger-than-expected 0.8% monthly increase in January.

Economic outperformance is also reflected in the considerable tightness of the labour market. An unforeseen resilience to the end of the Coronavirus Jobs Retention Scheme will see a reduction in near-term unemployment rate forecasts, and an upgrade to average earnings estimates; the OBR will likely still forecast a wage decrease in real terms, however. Indeed, the unemployment rate estimate of 4.8% for 2022 looks too high when compared with the current rate (3.9%) and our own forecast for 2022 as a whole (4.0%). Broadly, in its current state, the UK economy is better placed than the OBR had expected in October, albeit with significant downside risks.

In terms of the inflation backdrop, the commodity price spike, exacerbated by the invasion of Ukraine, will provide further upward pressure to an already elevated inflation profile. The OBR’s estimate for CPI inflation of 4.0% in 2022 looks very outdated – our own estimate for this year is +6.3%, and there are significant upside risks to that. Direct implications for nominal government expenditure from higher inflation are largely balanced out by the similar shift in government receipts, and so impacts on the public finances will primarily be governed by the policy shifts in response. This will depend upon the balance of the need for further outlays to abate the hit to real incomes and the extent to which this can be offset without further borrowing. In addition, a quarter of the government’s debt being in index-linked gilts leaves great exposure to the elevated inflation profile, particularly given the specified index is the Retail Prices Index (RPI) – our own forecast for RPI inflation in 2022 is currently +7.9% (OBR +5.0%).

The more favourable economic positioning will give the Chancellor more room for manoeuvre within the fiscal rules, but the requirement for cost-of-living mitigation in the near term may erode a good chunk of this. On balance, our best guess is that the kitchen sink remains plumbed in for now, and some room is spared for pre-election giveaways, even if it isn’t as much as Sunak would have hoped for.

Table 2: OBR Autumn 2021 macroeconomic forecasts (annual % change unless stated)

Source: Office for Budget Responsibility

Please note: the content on this page is provided for information purposes only and should not be construed as an offer, or a solicitation of an offer, to buy or sell financial instruments. This content does not constitute a personal recommendation and is not investment advice.