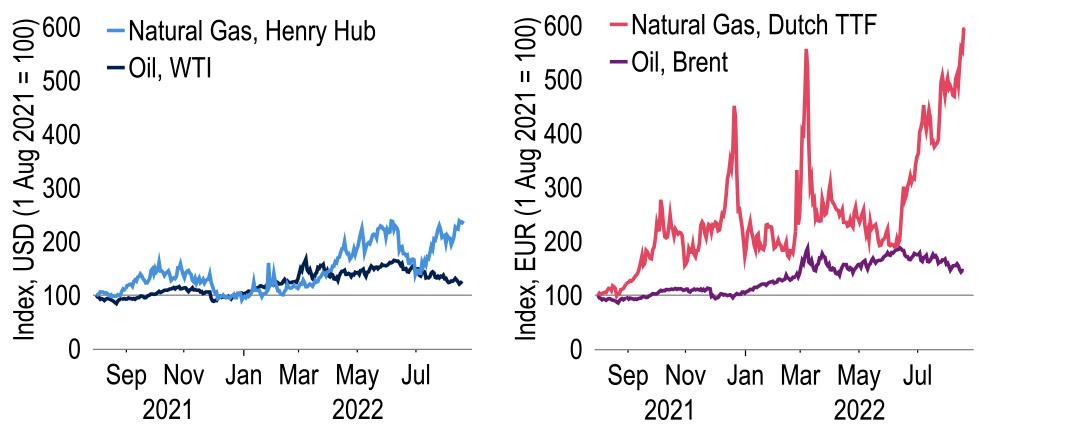

Rocketing gas prices, especially in Europe – to ten times the 10-year average – have markedly worsened the terms-of-trade shock faced by net gas importing nations. Particularly exposed are the EU and the UK, while the US is now a net gas exporter, underpinning the dollar’s outperformance. Even with some government mitigation, inflation is set to rise further, and recession now looks likely in the EU19 as well as the UK. Central banks stand to deliver more rate hikes, but as energy prices, sustained high food prices and China’s property slump squeeze demand – and supply pressures diminish – rate cuts may follow in 2023.

The Federal Reserve continues to walk the tightrope of raising interest rates to rein in inflationary pressures amidst a weakening economic backdrop. Although the two negative quarters of growth reported in the first half would qualify as a technical recession outside the US, and have pushed down our 2022 growth profile to 1.7% (previously 1.9%), this was largely a result of inventory swings. We see a more broad-based downturn on the horizon in Q2/Q3 next year, slightly later than in the UK and the Eurozone, reflecting the differences in energy vulnerabilities. Such a recession is likely to prompt the Fed to cut rates in three 25 basis point moves, starting from July.

Headwinds are mounting for the euro area outlook given the current energy crisis and continuing supply chain disruptions, which have been added to in Germany by the extremely low water levels in the Rhine. As such, we now envisage a recession in the EU19 over this winter. Our new Gross Domestic Product (GDP) forecasts stand at 3.1% and 0.4% for 2022 and 2023, respectively. European Central Bank (EBC) policy is expected to continue on a tightening path, with the deposit rate reaching 1.00% in December. However, we anticipate a policy hiatus will be seen over 2023 given the predicted economic downturn.

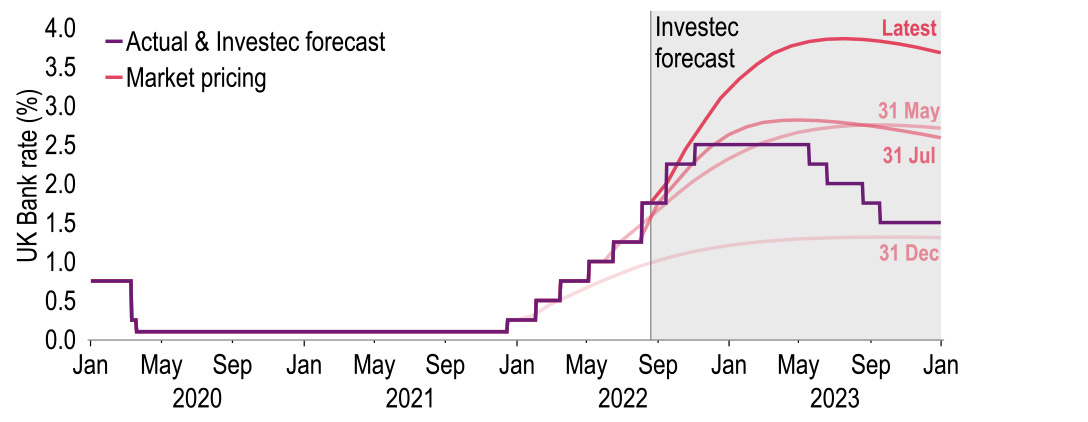

Soaring gas prices imply a rise of approximately 80% in October’s domestic energy price cap and likely a further material hike in January. Taken together with a poor 10.1% year-on-year Consumer Price Index (CPI) reading for July, we now forecast inflation rising to 13.4%, peaking in October and January. There are many unknowns. One is whether the Office for National Statistics will treat the existing (and potentially new) energy cost mitigation measures as price reductions. If so, some of these would reduce CPI inflation. Conservative leadership favourite Liz Truss had dismissed such ‘handouts’, favouring substantial tax cuts instead, but recently seems to have softened her line. In any case, UK markets now seem concerned about over-generous fiscal policy – at one stage late last week, rate markets were pricing in the bank rate rising to 4.00% next year. This is undermining rather than supporting the pound, currently below $1.18, a throwback to spring 2020 when currency markets were questioning the government’s herd immunity strategy in the early weeks of the pandemic.

Global

Globally, a disconnect has opened between oil prices on the one hand and gas on the other. Whereas oil prices have trended lower so far in the third quarter, gas prices have surged. The order of magnitude of the latter is far larger in Europe than in the US. Underlying this is the limited availability of alternatives to Russia as a supplier of gas to Europe. Only a small part of the global pool of liquefied natural gas (LNG) is not under long-term contracts; and distributing it relies on infrastructure (including pipelines and LNG terminals) that take time to put into place. Oil is more easily substituted, so its price has dropped on recession fears – and the chance of Iranian supplies coming back onstream were its nuclear deal revived.

Chart 1: Europe’s gas price surge dwarfs that in the US; oil trends are much more similar

Note: Oil price is spot, Gas is 1st position future

Sources: Macrobond and Investec

As always with a relative price change, there are winners – here, net gas exporters – and losers – net gas importers. Notably, the former now also includes the US. But energy exporters save a significant part of the extra revenue they receive, often via sovereign wealth funds, rather than spending or ‘recycling’ all their petrodollars, including on imports. Typically, savings in energy importing nations do not fall by an equivalent amount, so aggregate global demand – world GDP – slows. This effect is now even larger than in past energy shocks, as sanctions limit the ability of Russia to purchase goods and services from abroad.

The economic impact of soaring gas prices naturally depends not only on the share of gas supplies at risk but also on the proportion of the primary energy supply met by gas. China looks much better placed in this respect than Europe. However, its economy is struggling for other reasons, namely the property sector crunch and output disruptions resulting from the strict zero-Covid policy. This adds to the drag on global GDP, with greater knock-on effects elsewhere now that China accounts for 15% of world exports – compared to 4% in 2000 and 1% in 1980. Beijing is hence easing policy, using fiscal and monetary tools, including this week’s loan prime rate cuts.

A separate and further issue for the world economy to grapple with is that of the risk to food supply. Part of that remains the war in Ukraine, which has not only disrupted the distribution of grain from past harvests but also reduced the crops planted this year. Grain distribution has been addressed to some extent through the deal brokered by Turkey. But the war is ongoing, and this summer’s drought in Europe – a consequence of rising global temperatures – may delay a normalisation of prices. This could well prolong headline price pressures in the near term. Indeed, we have raised our inflation forecasts for this year and next in the EU19 and the UK.

But not all is doom and gloom. Fears of a global recession have led to an easing in global commodity prices. In time, that ought to help lower input price pressures.

But not all is doom and gloom. Fears of a global recession have led to an easing in global commodity prices – even in benchmarks for wheat and corn, as well as industrial metals. In time, that ought to help lower input price pressures. Moreover, global supply chains appear to be improving, notwithstanding ongoing issues in China. The hope is therefore that core inflation, which excludes food and energy, could be topping out soon. In the US, this point may already have been surpassed. But with headline inflation still so high, against the backdrop of very tight labour markets, we see central banks still very hawkish in the near term.

In the UK, we now expect the next move in rates to be a 50 basis point hike, to quell the risk of wages rising to compensate for past price rises and adding to costs and future inflation. Partly as a result of more hawkish central banks, but primarily as a result of what has become an exceptionally large terms-of-trade shock in Europe, we have cut our global GDP growth projections. Our new forecasts envisage recession extending to the euro area too, in the last quarter of this year and the first quarter of 2023, even if outright energy rationing is avoided. As inflation recedes, we see the Fed and the Bank of England removing some of the restrictive policies put in place, whereas the ECB should stand pat, as policy rates hold below neutral.

United States

The US labour market continues to run red hot. The July employment report was strong: monthly non-farm payroll gains far exceeded consensus at more than 528,000, pushing total non-farm payrolls above pre-pandemic levels for the first time. The continued strength of these figures seems curious given the depressed participation rate, as per the alternative household survey. Without a recovery in participation, we find it hard to see a scenario in which these robust payroll gains are sustained, primarily due to the dwindling pool of available labour, but also as the weaker economic backdrop starts to weigh on labour demand in the coming months.

For now, the labour market remains very tight, providing support for the Fed to continue with rate hikes to quell inflationary pressures, at least for the next couple of meetings. On inflation, despite being far above the 2% target, there are glimmers of hope: in July, CPI inflation pulled back to 8.5%. This was largely due to a fall in energy prices, but was accompanied by price drops in other sectors, such as used cars. Although it is not certain that peak inflation has passed, we think inflation will recede next year as rate increases and quantitative tightening (QT) weigh on demand, and eventually push the US economy into a recession, opening the door not to just to a policy hiatus, but also rate cuts in mid-2023.

We think inflation will recede next year as rate increases and quantitative tightening (QT) weigh on demand, and eventually push the US economy into a recession.

Interest rate markets had rallied strongly. Earlier this month they were pricing rates peaking as low as 2.75%, 100 basis points lower than in mid-June. 10-year US treasuries yielded 2.50% at one stage. This loosening in financial conditions went against the Fed’s tightening efforts, to the displeasure of Federal Open Market Committee members. Indeed, a plethora of hawkish Fed comments followed July’s meeting, when rates were lifted by 75 basis points, but bonds rallied in the absence of a commitment towards further large hikes. There was a similar reaction from markets and the Fed on release of the minutes, which highlighted Fed fears of overtightening. Overall, we maintain our view for a 50 basis point hike in September to 2.75-3.00%, but note that more speculation over lower rates would again be met by verbal intervention from the Fed.

The curve now sees a peak effective Fed funds rate around 3.75%, with cuts in the second half of 2023. Note too that the pace of QT is set to increase to $95bn per month next month, so at such a peak the stance of policy would be deep into restrictive territory. Despite the strong labour market, there are already indications that demand is slowing. Signs of housing market weakness continue to intensify. And final domestic sales growth currently stands as low as 1.2% year-on-year. Our call remains that a soft landing is wishful thinking and that the economy will fall into a mild recession next year, with rates reaching 3.00-3.25%, before the Fed changes tack and eases policy in the second half of next year.

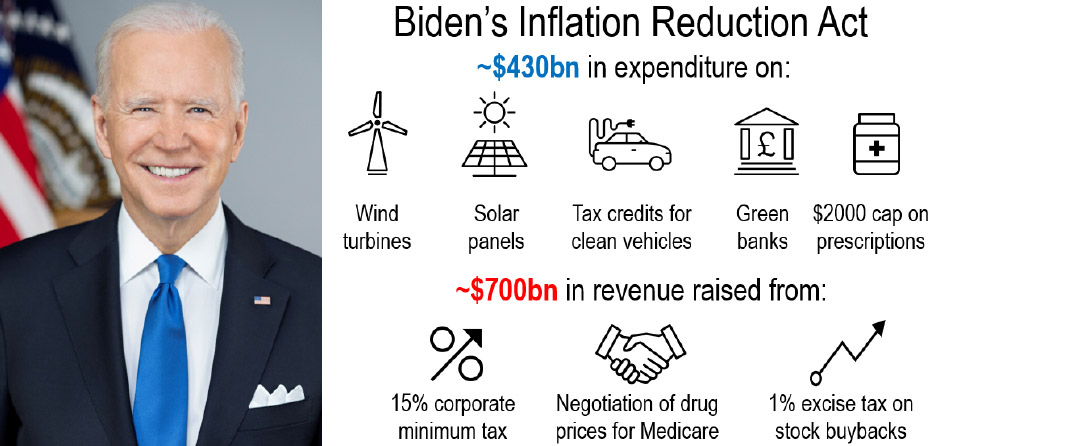

In light of the weaker economic outlook but high inflationary pressures, the Biden administration has been working on a package to stimulate the economy without stoking inflation. Following infighting within his own party, the new Inflation Reduction Act finally passed legislative hurdles and was signed into law earlier this month. The name of the act, however, may be misleading. Its inflation-reducing capabilities do not seem to apply to the short term, where it is badly needed. Indeed, renewable energy plants cannot be built overnight and the Medicare negotiations, for example, will not bring about lower prices until 2026 at the earliest – two years after the next Presidential election.

Chart 2: Biden finally receives party support for new slimmed down bill, but what is in it?

Sources: Image from US gov, illustration by Investec

Nevertheless, the eventual passing of the bill has helped Joe Biden and the Democrats in the polls. The overturning of the Roe versus Wade decision also boosted Democrat support. For several months, it was projected that the Republicans would take control of the Senate at the November midterms, but that tide seems to have turned – indeed, modelling by FiveThirtyEight now points to the Democrats left with at least 50 seats in the Senate. However, while their odds have shortened, the Democrats are still firmly projected to lose control of the House, which would hinder Biden’s chances of passing further legislation over the final two years of his term.

Eurozone

Second quarter EU19 GDP was better than expected at +0.6% quarter-on-quarter, bolstered by Italy, Spain and the Netherlands outperforming forecasts. However, although the third quarter may be supported by tourism, particularly in Southern Europe, the outlook is becoming bleaker. Energy supplies lie at the heart of the issue, with Russia having throttled gas supplies via Nord Stream 1 to just 20% of capacity. The critical question is whether the Euro area can avoid gas rationing this winter. For now, storage levels in Germany, at 79.5%, look on track to meet targets. Combined with efforts to reduce consumption, using alternative sources and assuming Russian gas supplies are not halted entirely, we believe rationing will be avoided, but remains a risk.

The critical question is whether the Euro area can avoid gas rationing this winter.

An unexpected additional headwind to the outlook has been the extreme heat in Europe this summer. One consequence is the extremely low water levels in the Rhine, particularly in Kaub, a notoriously shallow area where depths have plummeted to levels that make navigation extremely difficult. There are two issues with this. Firstly, it adds to supply chain issues, with barges only able to carry a quarter of normal loads with water at current levels. Secondly, it may exacerbate energy supply issues, given the waterway is used to transport coal to power stations up the Rhine.

This has led to further energy price jumps, given the potential need for additional gas supplies. It is these price rises that we see hitting the economy. The effects are set to vary depending on the exposure to higher costs and the level of fiscal support. Eastern European countries are especially exposed and there are potentially some signs of this already, with Latvia (‑1.4%) and Lithuania (‑0.4%) contracting in the second quarter. But the large economies are in focus, Germany especially. Given the energy backdrop and now extra supply chain issues, we see it slipping into a recession, a view we share for the euro area as a whole, with negative GDP growth now expected over the fourth quarter of this year and the first quarter of 2023. Our annual forecasts now stand at 3.1% for 2022 and 0.4% for 2023.

How the ECB responds will be an important determinant of the 2023 outlook. Given the inflation backdrop – we see the Harmonised Index of Consumer Prices reaching 10.2% – we expect continued tightening through the rest of 2022, our year-end deposit rate forecast standing at 1.00%. But looking into 2023, we predict the ECB will freeze policy tightening on account of the economic downturn. A cut in rates cannot be ruled out, but it is not our central case. One factor here is that we never expect ECB policy to enter a restrictive stance (ECB estimates of the neutral rate are around 1-2%), so arguably there will not be the same degree of pressure to cut rates as in the US and UK.

The ECB’s other focus is fragmentation risk, where July saw the first instance of ‘flexible reinvestment’ in pandemic emergency purchase programme (PEPP) assets, with peripheral holdings in Italy, Spain, Portugal and Greece rising €17bn, against a fall of €18bn in core German, French and Dutch bonds. Italy remains the key focus, but the 10-year yield spread has retreated to 228 basis points from a peak of 238 basis points in July. This comes ahead of next month’s election, where the centre-right group continues to hold a material lead over the centre-left, which has in recent weeks seen Italia Viva and Azione breaking away. Primarily, markets had been concerned about the potential direction of Italy under a centre-right government led by the Brothers of Italy. But comments by Giorgia Meloni have eased some fears, particularly over redenomination risks given commitments to the EU and its budgetary rules.

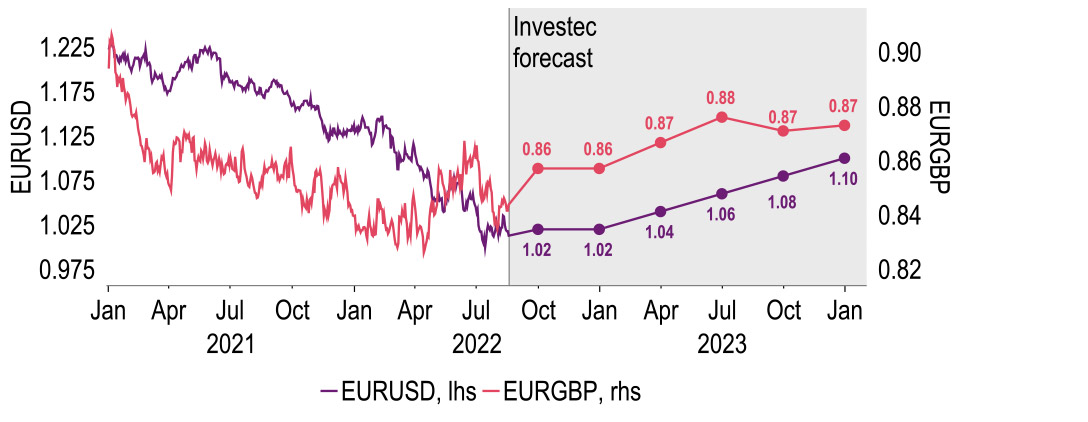

This has done little by way of supporting the euro, however, which has slipped back to below parity against the US dollar once again. Dollar dominance continues to ring through globally, as the energy outlook and derived economic woes paint a particularly gloomy picture for both the euro and sterling. Yet ECB interest rates are unlikely to move into ‘restrictive’ territory before the economy turns, so unlike for sterling, monetary policy should offer some support as other central banks cut rates. Our end-2022 and 2023 targets for the euro are unchanged, we expect the currency to remain weak at $1.02 until the end of this year but rise to $1.10 through the course of next year.

Chart 3: Renewed euro weakness now, but there is still good reason for a rise next year

Sources: Macrobond and Investec

United Kingdom

Additional bank holidays, such as June’s Diamond Jubilee, reduce GDP due to the lower number of working days. But is this effect waning? GDP fell by 0.6% in June, a more modest drop than over equivalent holidays over the past 20 years. The economy may be less sensitive to such events, thanks in part to more domestic tourism. But economic resilience may not persist for long given surging estimates of the energy price cap, which will put household incomes under huge strain. We now expect a longer recession in the UK, from the fourth quarter of 2022 to the second quarter of next year, with a peak-to-trough drop in GDP of 1%. Our 2022 GDP forecast is a touch firmer, at 3.8% up from 3.5%, but for 2023 is down to -0.2% from +0.6%, as rising demand for stored gas across Europe has put unrelenting upward pressure on medium-term gas contracts.

We now expect a longer recession in the UK, from the fourth quarter of 2022 to the second quarter of next year, with a peak-to-trough drop in GDP of 1%.

Accordingly, our utilities team has calculated the October cap will rise by 80% above £3,500, and at current market prices warns there would be a further 20% hike in January, as Ofgem now resets the cap quarterly. Such a rise on top of April’s 54% hike would lift annual household gas and electricity bills by £62.5bn, some 4% of disposable incomes, presenting the new prime minister with tough decisions on the extent and shape of any additional mitigation measures. Our forecasts do not embody any new policies of this type, which would of course support demand, with implications for monetary policy.

CPI inflation soared to 10.1% in July and although the main driver this time was food prices, utility costs will continue to be the leading influence over the coming months. An unresolved issue is how the current (and presumably forthcoming) mitigation measures will be treated in the economic data, namely whether as a price reduction – which would cut inflation – or whether as adding to income – the way we are treating them now. An official decision on this is due on 31 August. As things stand, we now expect a ‘twin peaks’ shape for the inflation profile at 13.4% in October and January, before lower energy costs result in inflation falling closer to 2% in the fourth quarter of next year.

Liz Truss is 1/16 favourite to beat Rishi Sunak in the Conservative leadership race. She has previously dismissed ‘handouts’ in the shape of further help to households to mitigate soaring energy bills in favour of substantial tax cuts. Truss has since softened her line on energy relief, which raises a possibility of still greater fiscal expansion. This sits uneasily with interest rates, which the Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) is raising to lower inflation. Fiscal prudence is an issue too, bearing in mind that public borrowing looks set to exceed £100bn this year and that debt exceeds 95% of GDP. An emergency Budget is rumoured for 21 September. How fiscally responsible it will be may be harder to assess if updated Office for Budget Responsibility forecasts are not sought.

Following the inflation data, we now expect a second successive 50 basis point hike in the bank rate to 2.25% in September. Our forecast still includes a final 25 basis point rise in November but we now foresee four (previously three) cuts next year, taking the bank rate to 1.50% by end-2023. Recently, the UK forward curve has risen sharply – at one stage last week it was pricing in the bank rate rising to 4% and remaining there for most of next year. This is not totally infeasible. For example, a vast fiscal package could bolster demand for longer, necessitating a hawkish pivot from the MPC. Or, wage growth could spike, resulting in the committee slamming on the brakes. For now though, this is not our base case.

Chart 4: Markets now expect the Bank rate to rise to nearly 4.00%

Sources: Macrobond, Investec

Over the past week, mid-2023 market bank rate expectations have risen by 60 basis points. This direction has been shared by other markets, but the UK curve has moved more sharply. Typically, this would result in a rise in sterling, but instead the pound has dipped to a new low for the year below $1.18. This disconnect probably reflects: i) discomfort with UK inflation (the first double-digit rate in the G7); ii) the UK’s exposure to gas prices; iii) angst over a gung-ho fiscal package, if and when Liz Truss becomes prime minister. Over the next year, our profile sees cable, or pound-dollar, around $1.20 as the UK avoids these risks, but sterling is vulnerable to testing 2020 lows of $1.14 if the government is irresponsible or unlucky.

Get more FX market insights

Stay up to date with our FX insights hub, where our dedicated experts help provide the knowledge to navigate the currency markets.

Browse articles in

Please note: the content on this page is provided for information purposes only and should not be construed as an offer, or a solicitation of an offer, to buy or sell financial instruments. This content does not constitute a personal recommendation and is not investment advice.