Major central banks not pivoting (yet)

While the economic outlook has darkened, we have upgraded our global growth forecasts for this year and next, partly because the Russian economy has outperformed expectations. We have also revised our currency projections to reflect a stronger dollar. Read our monthly Global Economic Overview for our latest forecasts.

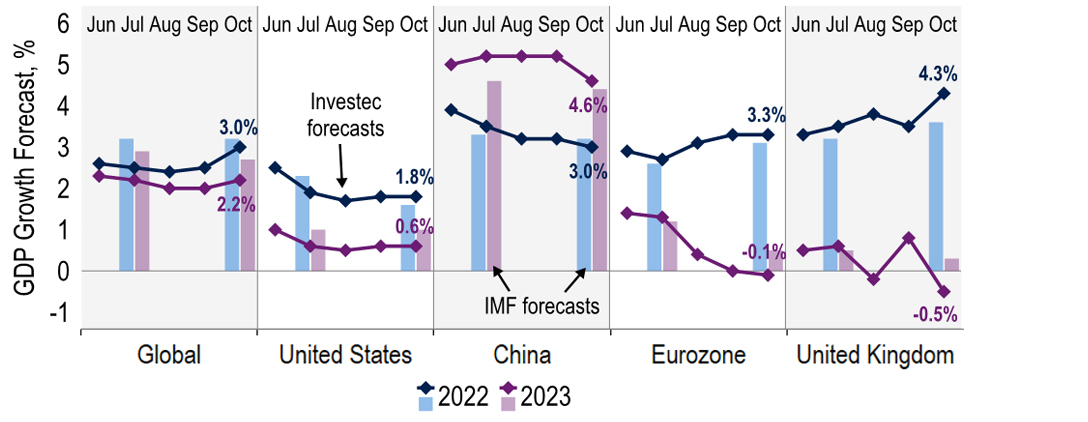

Global growth prospects are little improved. The Russo-Ukrainian war ensues, China has reaffirmed its zero-Covid policy, and monetary policy is being tightened further. That said, our global gross domestic product (GDP) growth forecasts are revised up to 3.0% this year and 2.2% next, partly due to the Russian economy beating expectations. Some central banks are approaching the end of their tightening cycle, but with inflation still high, the broad onus is still for higher interest rates. Financial stability has become another area of focus following turmoil in the gilt market and liquidity concerns in the US Treasury market. Meanwhile, dollar strength continues, with Japanese authorities intervening again to quell the yen’s rapid slide.

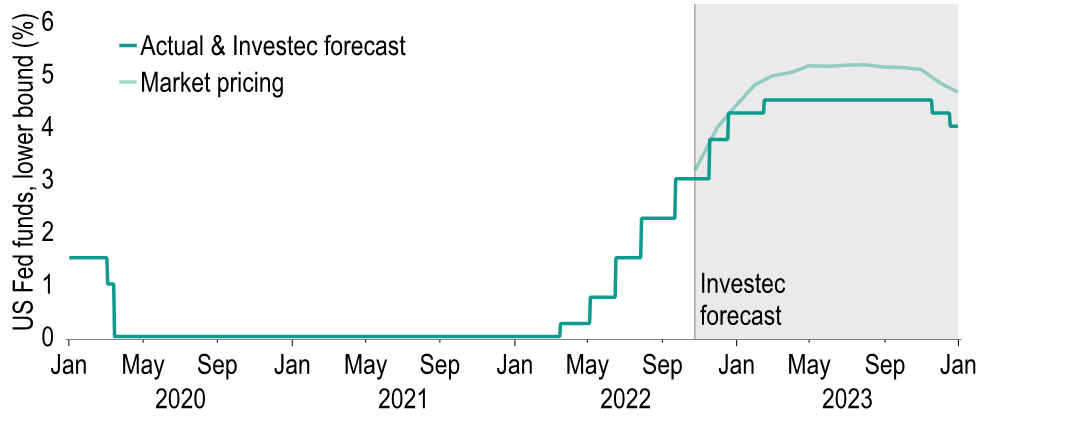

Although the Federal Reserve remains committed to monetary tightening to bring inflation back to the 2% target, in recent days there have been the first official hints that a Fed pivot could soon be on its way. This would be in line with our forecasts, which envisage the pace of tightening slowing following the 75-basis point (bps) hike on 2 November, resulting in a peak Fed funds target range of 4.50-4.75%, a 75bps upgrade relative to our previous forecasts. Under such restrictive rates, we expect economic growth to slow, with our forecasts looking for annual GDP growth of 1.8% this year and 0.6% next. This includes a recessionary period in the second half of 2023, prompting the Fed to rate cuts in the fourth quarter of 2023 to support the economy.

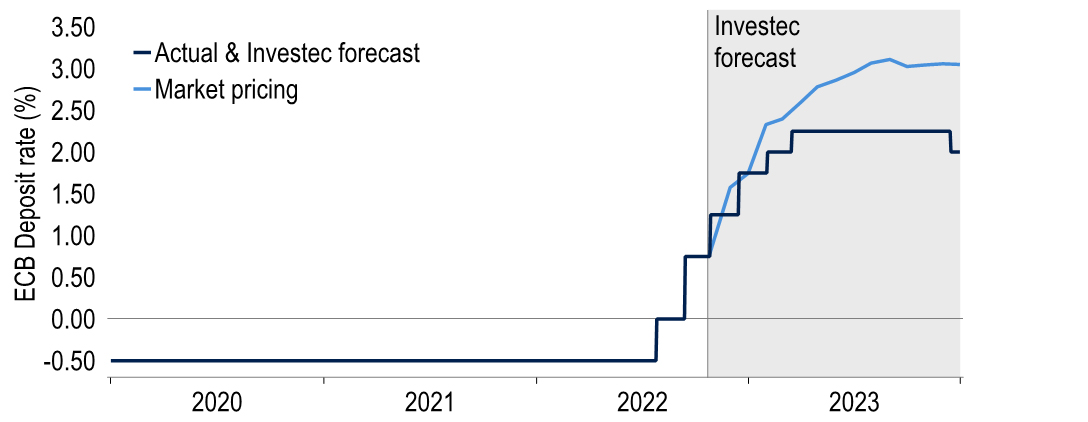

Headwinds continue to mount for the euro area, given cost-of-living pressures, energy issues, and a tightening in monetary policy. Ultimately we expect a recession this winter and a further one in the second half of 2023 - our GDP forecasts stand at 3.3% (2022) and -0.1% (2023). But despite this weak growth backdrop, the European Central Bank (ECB) is set to maintain a hawkish bias given the elevated levels of inflation, which should see the Deposit rate rise to a mildly restrictive level (2.25%) in early 2023. However, we expect a cut in rates late next year, given the economic downturn. Meanwhile, in the near-term further policy measures around quantitative tightening (QT), the terms of the ECB's third Targeted Longer-Term Refinancing Operation (TLTRO-III), and broader remuneration of bank reserves are also on the table.

Rishi Sunak has replaced Liz Truss as Prime Minister following her short-lived tenure. Together with Jeremy Hunt as Chancellor, this has reassured markets that the public finances are now on a sustainable path, following former Chancellor Kwasi Kwarteng’s ill-fated expansionary ‘mini’-Budget. The full Budget, alongside full OBR scrutiny, has been delayed to 17 November. We are still of the view that the MPC will need to raise the Bank rate but the U-turn on the fiscal stance means that we now see a peak of 4%, rather than 5%. We have also lowered our gilt yield forecasts and no longer see sterling heading to parity with the US dollar – our forecasts are now $1.15 for the end of this year and $1.22 for end-2023.

Global

Broadly, global growth prospects seem to have deteriorated further over the past month. The war in Ukraine is dragging on, with fears growing over nuclear escalation; China’s zero-Covid policy has been reaffirmed; and global monetary policy looks set to be tightened even further amid stubborn core price pressures. That said, our global growth forecasts are upgraded to 3.0% this year, and 2.2% next – in part at least due to the Russian economy outperforming expectations, as also highlighted in the International Monetary Fund’s (IMF) latest World Economic Outlook. However, the IMF remains more optimistic than us, mainly in advanced economies where we expect high interest rates to push most developed markets into a recession in 2023.

Chart 1: Evolution of our, and the IMF’s, global growth forecasts

Note: number annotations refer to the latest Investec forecasts

Sources: Macrobond, Investec

But on the bright side, one risk that appears to have dissipated is the global shortage of semiconductors. Indeed, supply chain difficulties on that front seem to have been alleviated sufficiently, without an overly dramatic hit to global trade, which is now not far from its pre-pandemic trend. However, the payback may now be in weakness in terms of demand faltering. When scarcity was an issue, firms ramped up inventory loading, moving to a just-in-case model. Yet, with activity slowing and inventories well stocked, demand in the sector has dried up. While this is somewhat idiosyncratic due to shifting sourcing strategies, there is growing evidence of a wider slowdown.

This is to be expected given the extent of monetary tightening enacted over this year, not least through the US. Monetary conditions indices highlight how the US dollar’s strength has added to the US’s restrictive policy, while hindering the efforts of other central banks. We now anticipate further interest rate rises, including from the Fed. Yet there is a growing consensus that tightening may begin to slow, stop, or even unwind in the next 12 months. The NBP has already paused its hikes, the BoC and the RBA’s latest moves were smaller than their last, and for the first time in this cycle, even Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) members have recently talked of the need to avoid ‘overtightening’.

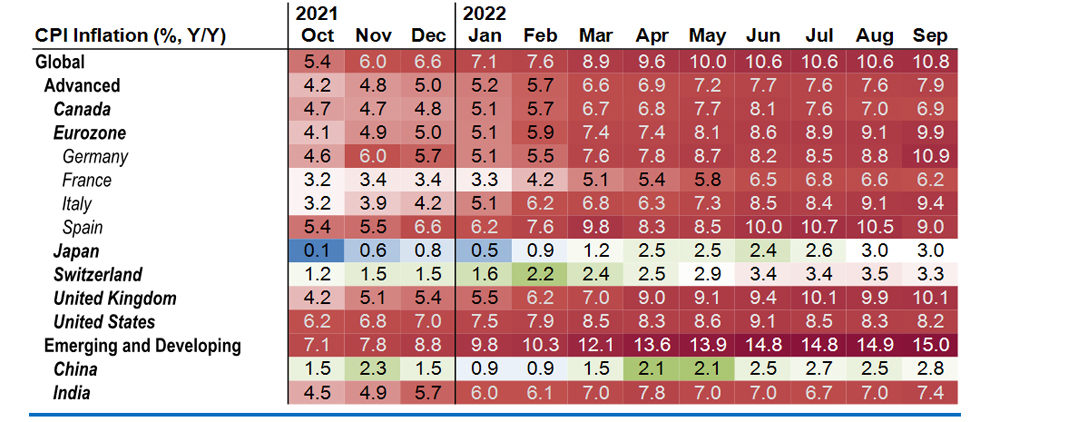

But for the time being, the main concern remains that inflation is still far above target in advanced and emerging economies alike. At these rates, the onus is on central banks to keep tightening. That said, in some countries, there are indications that headline inflation may have peaked, aided by the fall in the oil price (Brent crude is currently up 7% year-on-year, compared with average year-on-year growth of 60% in the first half of 2022). As tighter financial conditions increasingly bite, a pause at restrictive policy rates may follow. The next step would be rate cuts to return to a less restrictive monetary stance. But to maintain credibility, inflation will need to be visibly lower. We see late 2023 as the most likely timing for such a pivot.

Chart 2: Don’t stop me now – high inflation keeps the onus on central banks to hike further

Note: Shading does not account for non-2% inflation targets, such as that of the Reserve Bank of India

Sources: Macrobond, Investec

Over the past month, political decisions in the UK have had a substantial impact on markets, and not only domestically. The election of Liz Truss as Prime Minister by Conservative Party members coincided with a rise in the risk premium associated with the UK. But this became outsized only after the announcement of the mini-Budget, which was widely perceived to endanger fiscal credibility, ultimately threatening financial stability too. It took Bank of England emergency bond buying, U-turns on fiscal plans and the resignation of Truss to calm the waters, and even then, not fully. The lesson that maintaining credibility at all times is vital will be learnt globally.

A special case in the wider global picture remains China. Despite changes to the wider leadership, including the exclusion of current Premier Li Keqiang, the 20th National Congress of the Chinese Communist Party confirmed President Xi Jinping’s third term in office, as was expected. Contrary to some speculation prior to this event, Xi is sticking firm with the zero-Covid strategy. That is despite the economic harm associated with Covid restrictions. This is just one of the many headwinds facing the Chinese economy, with the country also suffering from slowing global demand and ongoing property market woes. We have cut our forecast for Chinese GDP growth for 2022 by 0.2% points to 3.0% and our 2023 estimate by 0.6% points to 4.6%.

United States

Inflationary pressures continue to cause a headache for the Federal Reserve. Although the annual rate of CPI inflation eased for the third consecutive month in September, it was once again hotter than expectations and the decline was largely due to falling energy costs. Accordingly, the core measure, which excludes such costs, hit a new multi-decade high. The continued step higher in core inflation is concerning, but there are positive signals that it may soon reach its peak. Indicators such as the Zillow rental index suggest that CPI rental inflation should top out soon and evidence has pointed to a marked easing of supply chains.

But for now, until there is undeniable evidence that inflation is heading back towards the 2% target, we expect the Fed to continue to tighten policy. Following the 75bps increase to the Federal funds target range for the fourth consecutive meeting on 2 November to 3.75-4.00%, the FOMC's post-announcement statement suggested that the ‘Fed pivot’ is on the horizon. It said the FOMC would consider the cumulative tightening effect and the lags in which monetary policy impacts economic activity, suggesting that the committee is actively discussing slowing the pace of rate increases. This was confirmed in the press conference in which Fed Chair Jerome Powell stated that the time to slow the pace of hikes could come as soon as the December meeting.

We envisage a peak Fed funds target range of 4.50-4.75% (prior: 3.75-4.00%). This consists of another 50bps hike in December and a final 25bps hike in February. We maintain that the restrictive stance of policy will ultimately push the economy into a recession in the second half of 2023, prompting rate cuts from the Fed. However, this is conditional on a loosening in labour market conditions, one sector of the economy that has so far remained resilient to higher interest rates.

Chart 3: All I want for Christmas is a Fed pivot

Sources: Macrobond, Investec

Monetary tightening is not just through rate hikes, however. In September, the Fed ramped up the pace of QT to $95bn per month. This came during considerable US Treasury market volatility, with yields rising across the curve and no obvious cause. Ten-year US Treasury yields hit their highest level since 2007 this month. A number of reports have pointed to deteriorating liquidity as a contributor to the current volatility. Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen has also expressed her concerns over this. In recent days however yields have eased from their peaks on expectations of an upcoming Fed pivot. On our rate views, we expect 10-year US Treasury yields to hit 2.75% by the end of 2023.

Yields will likely be driven lower as the economy turns and rate expectations fall. So far, the US economy is emitting mixed signals. While the labour market remains extremely tight, other elements have shown signs of a slowdown, and some have certainly turned. Indeed activity indices have been weaker of late, but the housing market is the first blood of higher interest rates. Leading indicators have been weak for some months, namely construction data and homebuilders’ confidence indices. But house prices are also on their way down - Case-Shiller and FHFA have reported seasonally adjusted declines for two consecutive months.

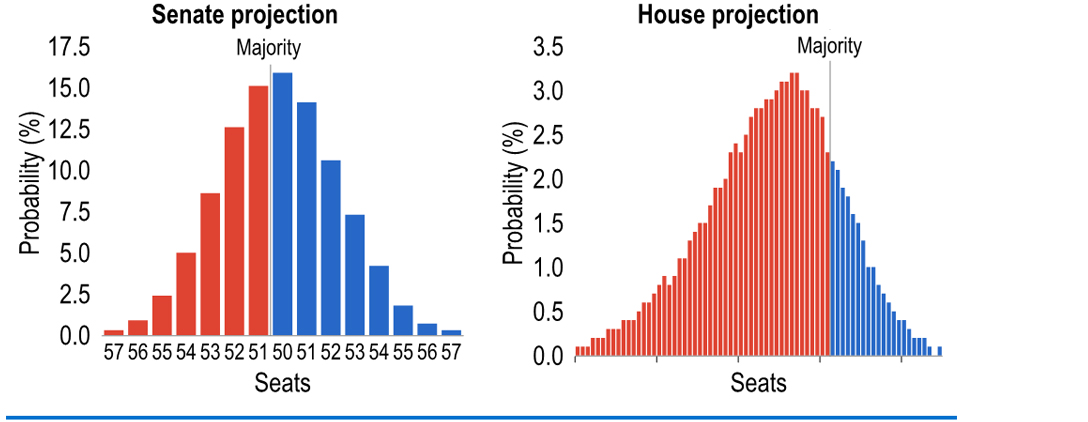

Chart 4: Projections now point to Republican gains at the midterms

Notes: A 50-50 seat split would see the Democrats hold the house due to VP Kamala Harris’ vote; Democrat count includes two independent senators

Sources: fivethirtyeight, Macrobond, Investec

This is no doubt due to surging mortgage rates – the average 30-year fix with Freddie Mac is now 6.94% following the Fed’s aggressive rate rises and rising sovereign yields. The FOMC’s stance has also boosted the dollar this year, as widely documented. This remarkable strength has been retained for longer than many, including ourselves, had expected. While interest rate differentials have not been the driver in cable of late, they remain authoritative in many pairs – notably US dollar-Japanese yen, which broke through 150 for the first time since 1932. Our forecasts reflect a stronger US dollar, but we still expect some of that strength to unwind through 2023.

Another feature of a robust currency is the tempered import price growth, an avenue of inflation troubling many economies. Lower inflation prospects had helped Joe Biden and the Democrats in the polls through the summer, as well as pushback against the Republicans (GOP) on abortion rights. However, that rally in support has subsided as inflation has remained high into the autumn. Surveys suggest that the state of the economy is the main concern for more Americans than ever, focusing on the rising cost of living. The GOP is now projected to win the House of Representatives and could regain control of the Senate too. Such a result would be a major obstacle for the Biden administration in delivering policies over the remaining 24 months of his term.

Eurozone

Headwinds continue to mount for the euro-area economy ahead of the winter. For example, purchasing manager indices (PMIs) have been in contractionary territory for the last four months as inflation, uncertainty and weakening demand have taken their toll. We expect there was marginal growth in the third quarter (+0.2% quarter on quarter), but the direction of the PMIs is telling. The situation will become more difficult in the months ahead, with energy remaining a key issue. German government support to shield households from energy prices provides an offset, but the price backdrop across the whole euro area, as well as the risk of gas and electricity shortages, remain. However, news on gas storage has been positive, with European countries broadly exceeding their storage targets.

The two most exposed countries to Russian gas, Germany and Italy, are 95% full. Combined with measures to reduce demand and alternative supply, a shortage scenario is hoped to be avoided. However, winter conditions provide a big unknown, with a cold winter risking shortages. Highlighting how tight the situation could be if alternative supplies to Russia were in short supply, average winter conditions could deplete German storage in months. Our central case envisages this scenario is avoided. Nonetheless, we still expect the euro area to suffer a mild recession this winter, given energy price pressures.

It should emerge from this in the spring, but given restrictive monetary policy and a subdued global growth backdrop, we see a double-dip recession occurring in the second half of 2023. Our forecasts stand at 3.3% in 2022 and 0.1% in 2023. This weakening growth backdrop leaves the ECB facing some difficult decisions, given the persistence of high inflation, September’s reading hit new highs on both the headline (9.9%) and core (4.8%) measures. Ultimately inflation concerns are primary and should see the ECB continue its path of tightening. Following a 75bps rise in the Deposit rate in October, we continue to see a peak of 2.25% in the first quarter of 2023. In turn, the ECB is focusing on its balance sheet and quantitative tightening (QT).

Chart 5: Rates expected to reach mildly restrictive levels, but 3% is too high

Source: Macrobond, Investec

We expect this to be sanctioned when rates reach a mildly restrictive level (2.25%) and done via a natural run-off of maturing securities rather than active sales. Assuming a start in April, we estimate that QT would shrink the balance sheet by €190 billion over 2023 to €4.75 trillion. Two reasons could be put forward for the recent urgency to discuss the matter. Firstly, a further tightening to address inflation would be the obvious candidate. However, a second could be put down to the implications of excess liquidity in a rising rate environment. With interest rates rising rapidly, the ECB is facing the prospect of paying significant sums on bank reserves rather than receiving them, as it has over recent years.

At the heart of the issue is that QE and liquidity operations such as TLTRO have increased excess reserves to €4.7 trillion. On an assumed 2.25% Deposit rate, this could cost the ECB €105 billion a year, an amount which is unlikely to be covered by income from its assets and has seen the Bundesbank and the DNB warn of losses and an erosion of capital. A broad approach to address this would be to apply a reserve tiering system. As an example, the ECB could use its existing two-tier system in reverse, applying the current multiplier of 6 to define the level of reserves which would receive the Deposit rate, while all above that would be remunerated at 0%, saving the ECB €22 billion.

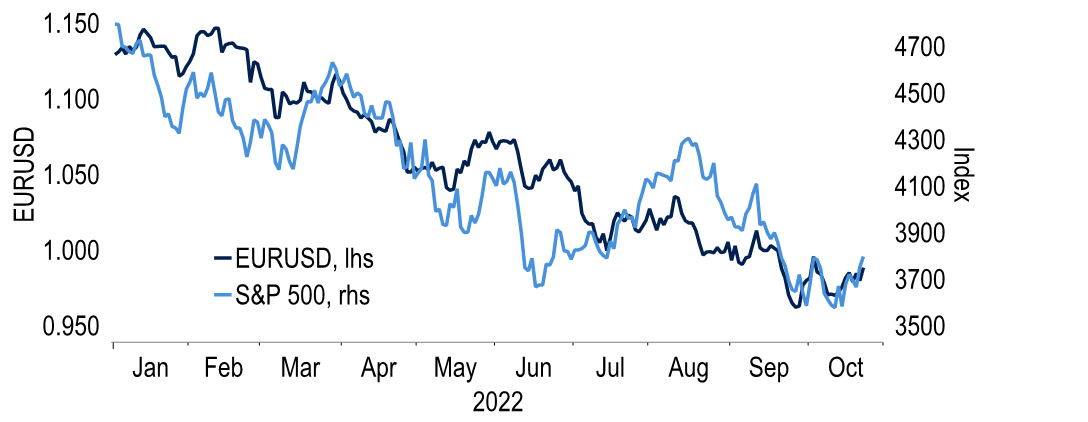

Chart 6: A weaker risk backdrop has contributed to the Euro’s weakness in 2022

Source: Macrobond

TLTRO-III terms will be part of this consideration given that differentials between the Deposit rate and its favourable terms to encourage lending means banks will benefit from simply depositing TLTRO funds at the ECB, a point the ECB wants to close. A tighter ECB policy stance should provide one supportive factor for the euro. Another is our expectation of some reversal in the dollar’s strength which has benefited from the risk-off sentiment in 2022 and contributed to its continued overvaluation versus the euro. Some sensible appointments in Italian Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni’s new government should also allay fears over its direction. Our euro-dollar forecasts stand at 0.99 in the fourth quarter of 2022 and 1.05 in the fourth quarter of 2023.

United Kingdom

Rishi Sunak has taken over as prime minister following Liz Truss’s resignation after 44 days in office. Mr Sunak has reappointed Jeremy Hunt as Chancellor, parachuted in by Truss after Kwasi Kwarteng’s attempts at a huge fiscal giveaway backfired, both politically and in terms of market volatility. Electorally the Tories have a mountain to climb. They are polling over 30% behind Labour, which at a general election would result in the Conservative’s near annihilation in parliament. While such an outturn is unlikely, there is a precedent. In Canada in 1993 under Kim Campbell, the Conservatives lost all but two seats. It took them 13 years to be re-elected.

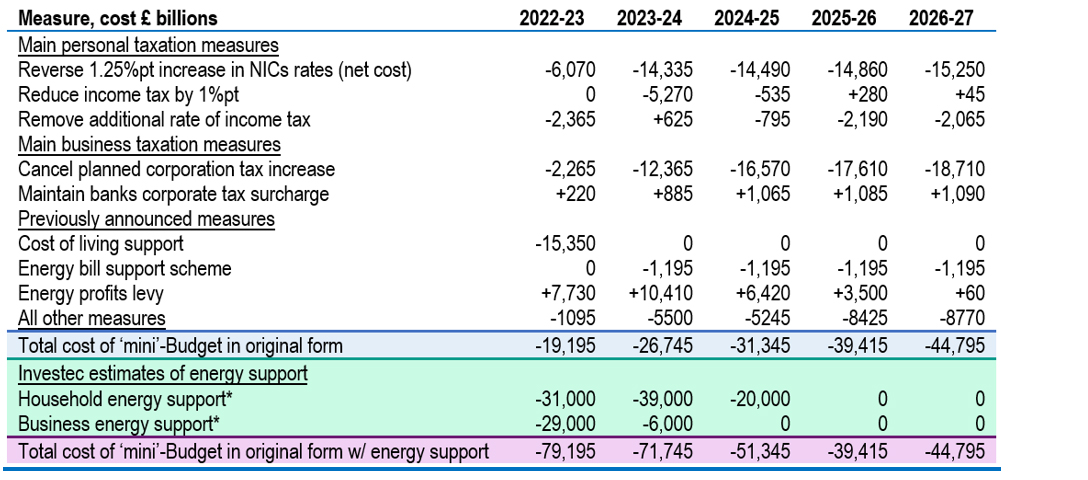

A catalyst for the changes was the market reaction to Kwasi Kwarteng’s ‘mini’-Budget. Most commentaries focused on a five-year annual cost to the Exchequer of £45 billion, but the government excluded the Energy Price Guarantee (EPG) from its costings. When this is included, our estimates suggest a cost of £75 billion in both years one and two. Mr Hunt has indicated that most of Kwarteng’s measures will be reversed and that he will replace the EPG next April with a more targeted (cheaper) scheme. In addition, he may look for a further £40 billion of savings at the fiscal event on 17 November, which may well be made up of both tax increases and spending cuts.

Chart 7: Chancellor Jeremy Hunt reverses 23 Sep’s ‘mini’-Budget

*dependent on market moves and length of government support

Sources: Gov.uk, Investec

Gilts bore the brunt of the markets’ thumbs down to the ‘mini’-Budget, as leveraged liability driven investment (LDI) pension schemes were forced to sell assets (including gilts) to raise fresh collateral. The Bank of England (BOE) bought £19 billion of gilts over 2½ weeks to stabilise the market, including index-linked stock for the first time. In September long ‘linkers’ saw a number of the largest daily yield rises in their history. The BOE intends to sell the gilts back in due course and to begin the delayed start to the active sales under its QT programme, though not long (20y+) stock for the time being. With markets more stable, we have lowered our end-2022 10-year yield target to 3.75% from 4.50%.

With CPI Inflation at 10.1% and the jobless rate falling to a 48-year low of 3.5%, the Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) raised Bank Rate on 3 November by 75bps, the largest single move in more than 30 years. The intended fiscal tightening effectively sharply reduced the risk of a hike of 1% of more. Indeed, rate expectations have eased on the reset of fiscal policy, and the pound has risen from its lows last month. From here, we expect the MPC to be more data-driven and are looking for the Bank Rate to peak at 4.0% before rates come down to 3.5% by end-2023 as a recession mutes inflation pressures.

The latest GDP figures show the economy's size was only equal to pre-pandemic levels in August. Also, it appears to have lost momentum in recent months. The impact of two additional bank holidays (in June and September) needs to be filtered out to gain a better impression of underlying trends, but surveys have also softened with, for example, the composite PMI hitting a 21-month low of 47.2. A recession early next year looks unavoidable, although the precise path of the economy will partly depend on the extent and the form of energy price support once the cap is unfrozen in April. For now, we are pencilling in a two-quarter downturn of some 0.8% from peak to trough. While GDP growth this year should exceed 4%, we look for a contraction of -0.5% next.

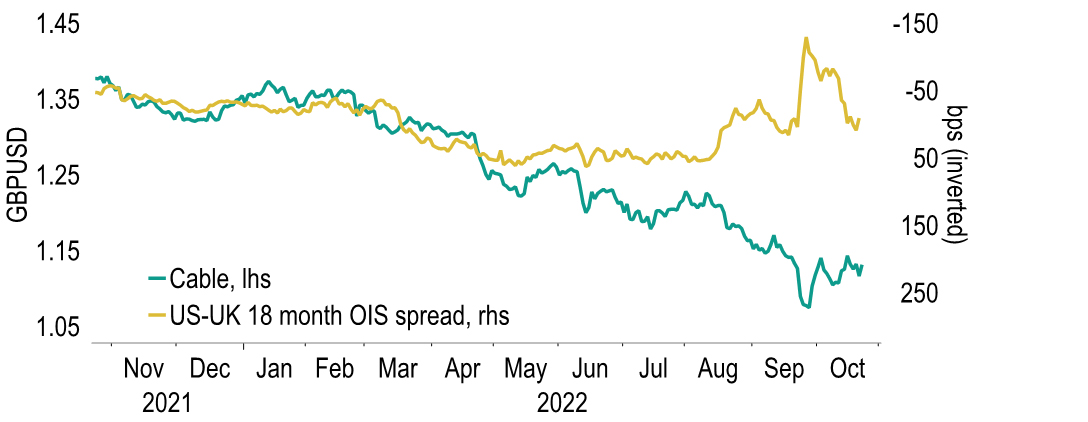

Chart 8: Sterling’s ‘credibility gap’ has narrowed, but is still significant

Sources: Macrobond, Investec

Without the latest fiscal U-turn, sterling might have fallen beyond parity with the US dollar – its trough was $1.03 and though it has since rallied, the currency pair’s relationship with prospective interest rate differentials, which held until mid-year, remains broken. Indeed, while credibility can be lost in an instant, it can take a very long time for it to be restored. Subject to political events, in particular, that Chancellor’s Hunt’s measures are passed, we expect sterling to eke out modest gains over the next year or so. Our targets are $1.15 at end-2022 and $1.22 at end-2023, helped also by a recovering euro. But we stress that there are material downsides should a credible fiscal stance not be forthcoming.

Get more FX market insights

Stay up to date with our FX insights hub, where our dedicated experts help provide the knowledge to navigate the currency markets.

Browse articles in

Please note: the content on this page is provided for information purposes only and should not be construed as an offer, or a solicitation of an offer, to buy or sell financial instruments. This content does not constitute a personal recommendation and is not investment advice.