Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has represented the biggest shake up in European security since World War II and a renewed downside risk to the global growth outlook. How long the conflict will last is still very much uncertain, but with some possible areas of compromise, a diplomatic path remains open. Under a baseline assumption of a ceasefire in the second quarter, we see a one percentage point hit to global growth this year – which is now forecast at 3.3% – while 2023 growth is downgraded by 0.3 percentage point to 3.4%. A key point here is commodities, where supply issues risk extending the bottlenecks of the past year, and further price increases could exacerbate the current cost-of-living pressures. Covid-19 cases have also been rising in a number of jurisdictions and China has implemented several city-wide lockdowns recently, adding to global problems.

The Federal Reserve kicked off its tightening cycle this month with a 25 basis point hike to the Fed funds target range, up to 0.25-0.50%. Reflecting on the high inflation backdrop, Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) members also scaled up their rate expectations for the year ahead, with a median view of a further 150 basis points of hikes in 2022. Our base case is for a softer pace of tightening, especially when compared to market expectations, which have another 200 basis points of hikes priced in this year. In contrast, our base case is for four further 25 basis point hikes by year end, although we do recognise the possibility of a 50 basis point increase in May. This is based on the assumption that the risk of a ‘hard-landing’ will encourage the Fed to take a more gradual approach to tightening.

The Eurozone’s geographic proximity to the conflict in Ukraine and its greater trade ties with Russia and Ukraine naturally leave it more exposed economically to the war than other parts of the world. A key worry is energy dependency on Russia; reducing it will not be simple, nor cheap. As such, we have cut our 2021 Gross Domestic Product (GDP) growth forecast from 4.1% to 3.3%, while 2023 remains unchanged. However, we expect the European Central Bank (ECB) to stick to a fairly cautious course in moving towards rate hikes, certainly relative to market pricing. Our forecast remains for a first 25 basis point rate hike in December this year, followed by two more rate rises in 2023. The euro’s path to strengthening now looks delayed.

Consumer Price Index (CPI) inflation now stands close to a 30-year high of 6.2%. Looking ahead, the domestic energy price cap is set to rise by 54% next month, with energy futures currently pointing towards another hefty surge in October, and it seems as though the chancellor’s mitigating measures will have no impact on CPI. Accordingly, we now forecast peak inflation of 8.9% in October. This leaves household consumption vulnerable. In the recent Spring Statement, the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) forecast real disposable incomes declining in both 2022 and 2023, with consumer spending supported by excess savings built up during the pandemic. While we broadly concur, there are clear downside risks and we judge the short-term yield curve, which is pricing in a bank rate of above 2% by the end of 2022, to be too aggressive. We now expect the Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) to keep rates on hold in May but maintain our year-end target of 1.25%. We have downgraded our pound-dollar, or cable, forecast for the end of the year to $1.35, from $1.42 previously.

Global

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine represents the greatest shift in European security since WWII. But analysis of the situation on the ground suggests Russia’s advance has not gone to plan amidst stiff resistance, logistical issues and heavy losses. Will this and sanctions change President Vladimir Putin’s approach? A Russian withdrawal without some form of ‘win’ seems unlikely. But the announcement that Russia will now focus on the Donbass area hints that it may be scaling back its objectives. Hopes remain over a diplomatic solution, given there are some areas of compromise, such as Ukraine’s position on NATO and the possibility of it becoming a neutral state. Talks are difficult, but in forming a baseline view we assume a ceasefire is agreed by the end of the second quarter, although we acknowledge this is far from certain.

As such, we assume some but not all sanctions are unwound. Nonetheless, we suspect that sanctions, voluntary corporate withdrawals and a hesitancy to export to Russia will have done damage. This, coupled with a sharp depreciation in the currency – the rouble has fallen 23% (previously as much as 46%) against the US dollar this year – should see a severe impact on the Russian economy. Trying to estimate a precise figure is difficult. However, on examination of countries that have experienced sanctions, a currency crisis or similar, the outlook looks bleak. Our estimate is that Russia will see a 10% contraction this year.

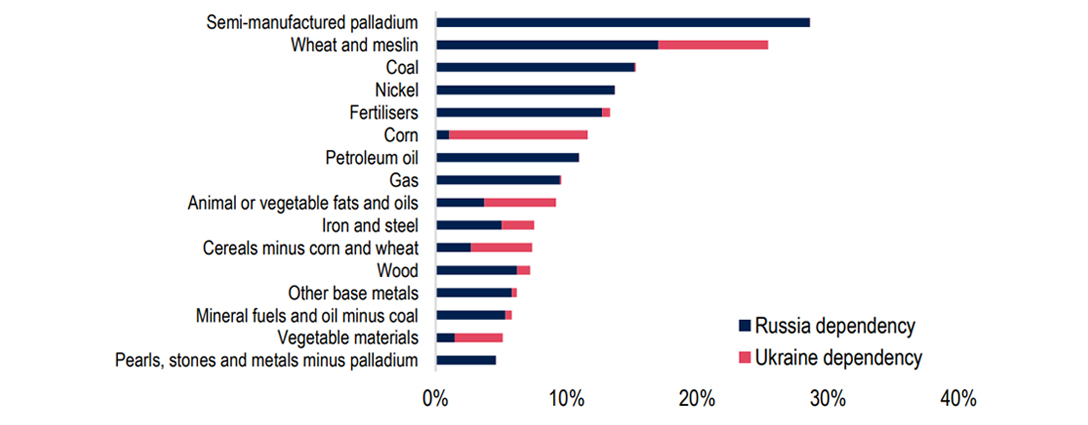

The impact on activity is set to spread beyond Ukraine and Russia’s borders. A key factor here is commodities, with Russia and Ukraine representing sizeable proportions of global trade in energy, wheat, fertilisers and others. Energy has been a focus, given Europe’s dependence on Russian gas, with little in the way of sufficient and easily available substitutes. To date, pipeline gas flows to Europe have largely remained unchanged, but a risk would be if Russia were to cut off supplies. Although it seems unlikely at present, this would lead to shortages and rationing. However, developments related to foodstuff are also a key concern. Ukraine and Russia represent almost 30% of global wheat exports.

Chart 1: Global exports accounted for by Russia and Ukraine

Sources: BACI, Investec

Ukraine itself exports around 20 million tonnes of wheat per year, the supply of which at least in the short term is at risk of disappearing, given the war’s impact on exporting capacity and ability to sow. Russia has also introduced a partial wheat export ban. However, wheat is not the only issue: fertiliser and animal feed are also set to see an impact, which will push up food prices. This has led to the UN warning of a global food crisis. Commodity prices are rising broadly as a result, which will negatively impact consumers and businesses across the world. Broadly, the supply shock in commodities from the war in Ukraine is set to prolong some of the supply chain issues that emerged from the pandemic and which we hoped would begin to ease.

The supply shock in commodities from the war in Ukraine is set to prolong some of the supply chain issues that emerged from the pandemic and which we hoped would begin to ease.

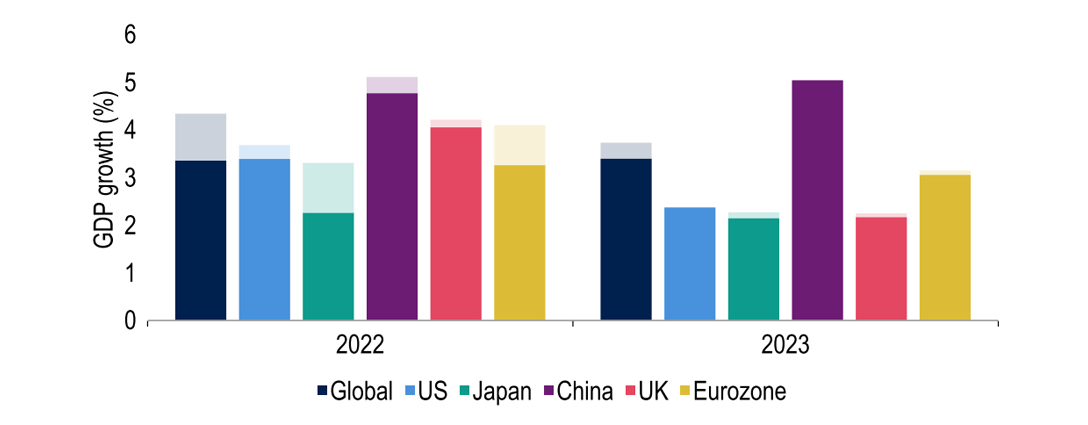

As such, headwinds to global growth are rising; we have pushed down our view of world GDP growth for this year by one percentage point to 3.3%. Notably, half of this downgrade is accounted for by Russia and Ukraine. The other 0.5 percentage point is accounted for by markdowns across the rest of the world, albeit by varying degrees depending on linkages to the crisis. For example, amongst developed markets we assume the euro area will take the biggest hit, with a 0.8 percentage point downgrade, the US less so at 0.3%. Our global forecast for 2023 is 0.3 percentage point lower at 3.4%. Russia, we suspect, will contract by a further 5%, but we assume the end of hostilities will allow a rebuilding of Ukraine, based on something resembling the Marshall Plan.

Chart 2: Global growth picture downgraded

Note: Faint areas indicate previous forecasts

Sources: Macrobond, Investec

Although firmly on the backburner news wise, Covid-19 continues to bubble away. Global cases are now rising again, largely driven by South Korea which is currently reporting an average of 350,000 cases per day. China, meanwhile, continues to pursue its zero-Covid strategy, which has seen activity restricted in cities such as Shanghai and Shenzhen. Despite outperformance in the first two months of the year and likely upcoming policy easing, given the offset of lockdowns and adverse impacts from the war, we judge the net effect to be negative. Our Chinese growth forecast in 2022 is therefore lowered from 5.1% to 4.8%.

United States

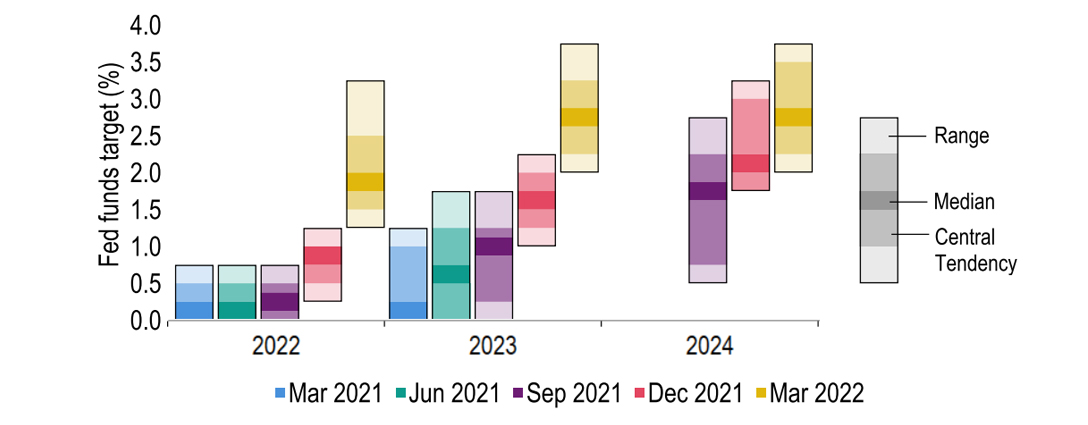

In what is expected to be the first in a series of hikes, the FOMC kicked off the tightening cycle in March with a 25 basis point increase to the Fed funds target range to 0.25-0.50%. The median view of the committee is for this to be followed by a further 150 basis points of hikes this year, while markets have priced in around 200 basis points for the rest of 2022. In absence of an emergency meeting, market pricing would suggest at least two 50 basis point moves this year. On top of this, quantitative tightening is set to begin soon, which Fed Chair Jerome Powell estimates to be equivalent to a further rate hike. This aggressive path for tightening reflects the FOMC’s unease about the high rates of inflation – CPI hit 7.9% year-on-year in February.

Chart 3: Fed funds rate expectations are considerably higher, but so is the dispersion of views

Note: Projections are given as the Fed funds target range

Sources: Federal reserve, Macrobond, Investec

Despite the sharp profile of rate hikes, there is vast uncertainty behind such projections. The range in views among the committee members on the appropriate level of the end-of-year Fed funds midpoint amounts to 175 basis points. On the markets side, although higher rate expectations have resulted in Treasury yields moving considerably higher across the board, this has been more pronounced at the short end. As such, we are seeing a flattening in the yield curve; the two-year to 10-year spread has fallen by around 60 basis points since January. A flattening in the yield curve often suggests that investors are concerned tightening plans could choke off economic growth.

Although inflation must be addressed, we consider current market pricing to be too aggressive and, if followed, could result in the Fed being unable to deliver the elusive ‘soft-landing’ for the economy. Some Fed members have even factored this into their own projections, with the dot plot revealing at least two members envisaging an easing of rates in 2024. Indeed, if the situation in Ukraine weighs on growth – our 2022 US GDP forecast has already been downgraded by 0.3 percentage point – we expect the Fed will take a more cautious approach to tightening. For now, we are sticking with our call of four further 25 basis point hikes this year, but recognise the possibility that the Fed may want to signal its tough stance on inflation with a 50 basis point move in May.

A higher rate environment should act to cool the US housing market. Over the course of the pandemic the housing market has performed strongly; the average house price has gained around 30% as the market has been supported by ultra-low rates and fiscal stimulus. Although many housing market metrics continue to signal strength – inventories are still unprecedentedly low and housing starts are high – warning signs are slowly appearing. Climbing policy rate expectations are pushing mortgage rates higher, which has weighed on housing affordability and ultimately mortgage applications. The risk of a housing market slowdown on the horizon supports our call for a less aggressive pace of tightening.

Since the invasion of Ukraine, the dollar has seen gains via risk aversion and added upward pressure, given the US is better placed both geographically and dependency-wise to deal with the crisis. The rapid prospective monetary policy tightening relative to other major central banks also supports dollar holders.

The high inflationary backdrop and the various headwinds to economic growth have not been supportive factors for President Joe Biden as he heads towards the November midterm elections. Current polling by FiveThirtyEight places his approval rating at 42%, 11 percentage points lower than when he took office. The president also faces resistance from within his own party. Due to the razor-thin majorities the Democrats hold, West Virginia Senator Joe Manchin has been able to block key election pledges from passing the Senate. To advance his agenda, the president needs Manchin’s support, or a strong performance at the midterms. On current polling, the latter looks unlikely.

Since the invasion of Ukraine, the dollar has seen gains via risk aversion and added upward pressure, given the US is better placed both geographically and dependency-wise to deal with the crisis. The rapid prospective monetary policy tightening relative to other major central banks also supports dollar holders. We still view the dollar as overvalued in general, but we expect it to retain more strength in the medium term than we had judged previously. Meanwhile, with the Bank of Japan struggling to keep yields in check, the yen has dived this year, now sitting at 124 against the dollar. We expect a stabilisation at ¥120 by the end of the year.

Eurozone

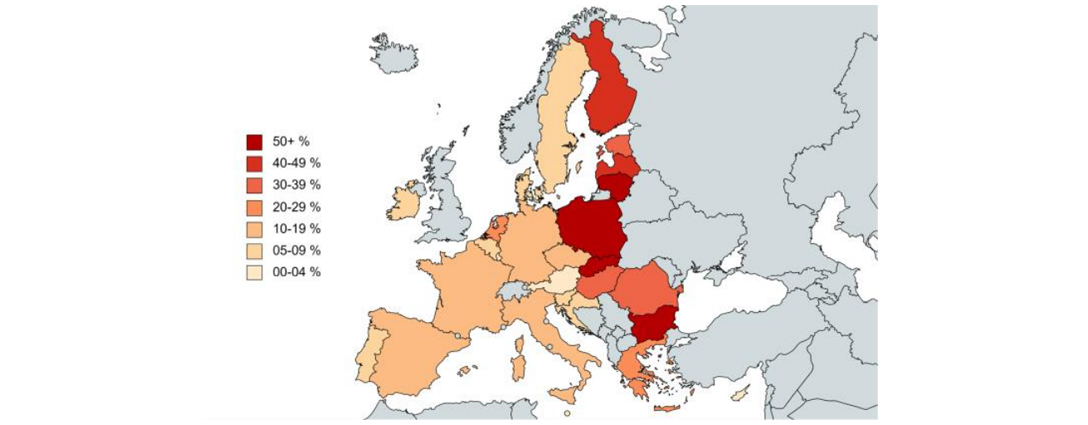

Among the major economic regions, the Eurozone stands to be hurt the most by the war in Ukraine – unsurprisingly given its geographic proximity. We have cut our 2022 GDP growth forecast from 4.1% to 3.3%, while 2023 remains unchanged at 3.1%. In part, this reflects the 19 euro members’ direct trade exposure. In aggregate though, it is not huge: exports to Ukraine and Russia were 0.6% and 2.9% of 2021 total goods. However, the key concern is that 62% of the Eurozone’s energy needs are met through imports, and 15% of energy imports come from Russia. Should these be halted, whether by Russia or by sanctions being extended to the energy sector, this would impart a major hit.

The key concern is that 62% of the Eurozone’s energy needs are met through imports, and 15% of energy imports come from Russia.

That is not our baseline case, but even without this, the lack of easily accessible substitutes has turbo-charged already high European energy prices. Given the cost, governments will only be able to mitigate the impact of this large terms-of-trade shock on household real incomes to some extent. Adding to the fiscal bill will be huge refugee flows. On top of that, governments will have to fund some major structural shifts to pivot away from Russian oil and gas. Accelerating the energy transition will be challenging, albeit to varying degrees within the EU19. The obvious long-term answer is renewables output, but as an interim, Germany for example is not only building its first liquefied natural gas terminals but may also delay its phase-out of coal-fired power plants.

Chart 4: Dependency on Russia as a supplier of imported energy varies across the EU

Sources: Eurostat, mapchart.net, Investec

From the point of view of inflation, the impact of the war in Ukraine on Eurozone prices stands to be substantial. Even with government help to mitigate pressures at the consumer level, an additional boost to already high energy prices is a given. But, crucial as it is, energy is not the only raw material affected by the war. Food prices stand to see extra price pressures, both directly – with Ukraine a substantial wheat exporter – and indirectly via fertilisers. Supply chain disruptions in some industrial goods, which had just started to abate, may also be prolonged. We have raised our inflation estimates for 2022 by two percentage points to 6.6% and by 0.5 percentage point for 2023 to 2.2%.

High as that is, it is below the ECB’s annual average CPI forecast in its ‘severe scenario’, although above the ‘adverse’ and baseline cases presented in its March Staff Projections. These had only incorporated energy price effects rather than the wider impact of the war. Still, even the baseline forecast was raised substantially, justifying the Governing Council charting an accelerated path towards tightening. We continue to expect quantitative easing tapering to finish in the third quarter and a first rate hike in December this year, with two more to follow in 2023. Market pricing is more aggressive. But given lags between hiking and impacting inflation, and the weaker growth outlook, a more cautious path seems plausible despite high near-term price pressures.

Relative to the UK and the US, the Eurozone’s path to monetary tightening has been modest to date. Prospects of relatively greater economic harm to the EU19 as a result of the war in Ukraine, importantly coupled with the larger bond market selloff in the US than in Germany, have contributed to the euro underperforming further against the dollar since the start of the invasion. This extends the previous trend. For the time being, a swift reversal seems unlikely. We have therefore scaled back our euro forecasts, now expecting it to finish the year at $1.15 against dollar and $1.18 next year. Against sterling, we expect an end of 2022 level of 85p and 84p at the end of 2023.

The cost-of-living squeeze is critical for the political landscape too – in France, voters cite purchasing power as the issue that matters most to them ahead of the presidential election. Polls open on 10 April for the first round, before a runoff vote two weeks later. Emmanuel Macron is vying for a second term in the Élysée, with Marine Le Pen the main challenger. Polls suggest a comfortable victory for Macron. With his challengers mostly at the extreme ends of the political spectrum, and especially in a time of uncertainty, he is viewed as the safer option. In his recently detailed campaign, Macron set out a plan for greater state involvement across the board, which he hopes will bring security to the economy.

United Kingdom

CPI inflation now stands at a new near 30-year high of 6.2%. While price pressures are broadening out, an increasingly large driver is domestic gas and electricity costs. A definitive answer has yet to be given on how Chancellor Rishi Sunak’s measures to cushion households from the 54% rise in the energy price cap in April will be treated in the CPI. But it seems as though they will be classed as an income transfer, not a price reduction. If so, there would be no offset within the inflation numbers to the rise. Our utilities team also estimates October may see a further hike of 48%. We now see UK inflation peaking at 8.9% in October, but in the event of a sharp drop in the energy cap next year, inflation could fall below 1% over 2023.

We now see UK inflation peaking at 8.9% in October, but in the event of a sharp drop in the energy cap next year, inflation could fall below 1% over 2023.

As noted on many occasions, households are benefiting from a cash buffer of excess savings built up over the Covid-19 pandemic. This is material – our estimate is £161bn, or 12% of consumer spending last year, which will help many, if not all, households to maintain spending patterns in the face of soaring inflation. It is worth noting that corporates also enjoy a similar cushion, which we put at £118bn. A key difference is that this largely results from higher borrowing at the start of the pandemic, rather than fiscal giveaways, such as the furlough schemes in the case of households. Either way, it also helps to alleviate fears of a cash crunch.

The household buffer could be critical. At the Spring Statement, the OBR forecast real household disposable incomes falling in 2022 and 2023, with household consumption – projected to rise 5.4% this year and 1.0% next – supported by a falling saving ratio and in part by some households drawing down on pandemic savings. While we broadly agree, we are mindful that events may not play out quite as intended. GDP did get off to a good start in January, expanding by 0.8% on the month, after December’s 0.2% drop. Even so, we have downgraded our 2022 forecast to 4.0% from 4.2%, with a risk of a softer outturn if consumption dynamics turn out less favourable. Our 2023 forecast stays at 2.2%, but again we are mindful of downside risks.

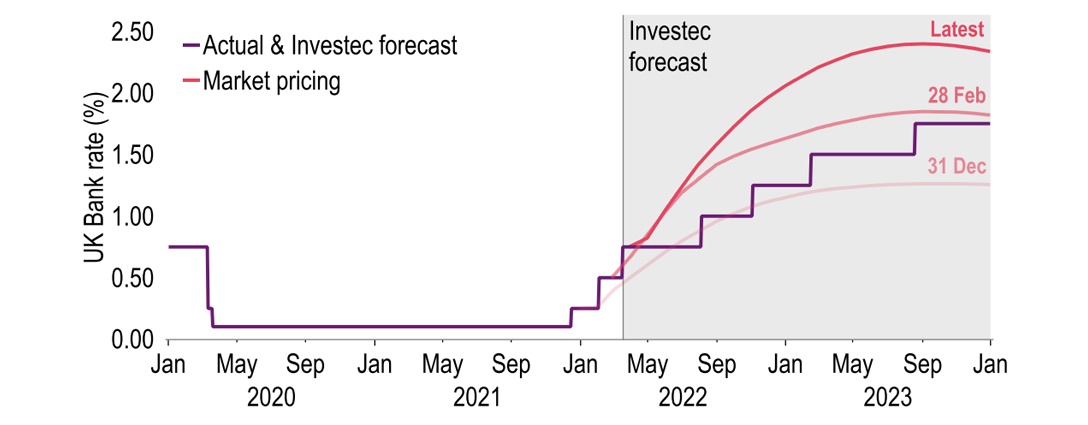

The tone of the MPC’s third successive hike in the bank rate by 25 basis points to 0.75% was a far cry from the Fed’s hawkish narrative. Deputy Governor Jon Cunliffe voted for unchanged rates. The Bank of England (BoE) was cautious over the need for further moves, stating: “Some further modest tightening in monetary policy might be appropriate in the coming months.” By contrast, the median FOMC view is for seven hikes this year – and the curve has become more aggressive still, close to pricing in a 2.25% bank rate by year-end. Our end of the year target for UK interest rates remains 1.25% and we are now of the view that rates will remain on hold in May, as the BoE’s concerns over downside risks to growth take centre stage.

Chart 5: UK interest rates – market pricing getting carried away?

Sources: Macrobond, Investec

Since the government relaxed all of England’s remaining Covid-19 restrictions, infection rates have climbed again. This is not on the scale of the surge recorded in parts of Asia, in particular South Korea. Even so, the resurgence means new cases have doubled from late February’s trough and are now averaging 86,000 per day. Fatalities have risen and are now averaging over 130 per day. At 17,400, the number of Covid-19 patients in hospital is only some 3,000 below the recent peak in early January. But numbers in mechanical ventilator beds have risen more modestly, offering broad hope that the average severity of infections has eased and that the government’s strategy of ‘living with Covid’ is sustainable for now.

Cable fell to pre-Brexit deal levels of $1.30 this month following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, and we anticipate downward pressure on the dollar if and when the war subsides. But the UK curve looks so aggressive that to the extent there is a connection between rate and foreign exchange markets, sterling may be vulnerable should the MPC hold steady in May, as we now expect. Our forecasts now see cable holding at $1.32 through the first half of this year, but gaining in the second half to $1.35 by the end of the year – a sizeable downgrade from our $1.42 forecast previously – and rising next year to $1.40 the end of 2023. This translates to a relatively range-bound euro-sterling rate, which we see ending this year and next at 85p and 84p respectively.

Get more FX market insights

Stay up to date with our FX insights hub, where our dedicated experts help provide the knowledge to navigate the currency markets.

Browse articles in

Please note: the content on this page is provided for information purposes only and should not be construed as an offer, or a solicitation of an offer, to buy or sell financial instruments. This content does not constitute a personal recommendation and is not investment advice.