Weaker growth complicates central banks' balancing act

The outlook for global growth has weakened as the Ukraine-Russia war looks set to be protracted and Chinese activity remains stagnant due to lockdowns. Therefore, we have downgraded our economic growth forecasts for the US, the Eurozone, and the UK in our latest Global Economic Overview, and see central banks frontloading rate increases this year to tackle surging inflation before reducing the speed of tightening in 2023.

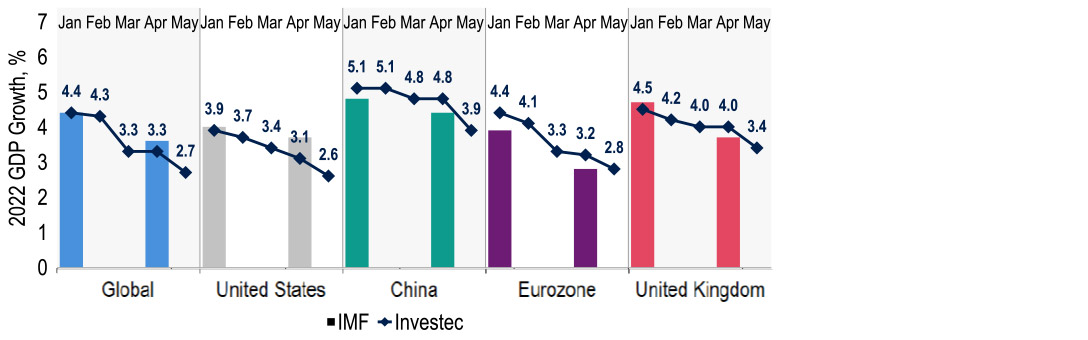

The global growth outlook has worsened in the last month. The war in Ukraine looks set to be protracted, and Chinese activity is stagnant due to lockdowns. This will hamper supply chains and add to inflationary pressure, which further fuels general suppositions of a global slowdown. Our forecasts for most individual economies are downgraded, and as such our global growth forecast for 2022 is cut by 0.6 percentage points to 2.7%, with our forecast for 2023 at 3.0%, compared to 3.4% previously. These slowdown fears have torn through asset markets. Equities have slumped and interest rate markets have rallied, to the extent that much less tightening is now being priced in for next year – a risk we have highlighted for some time now.

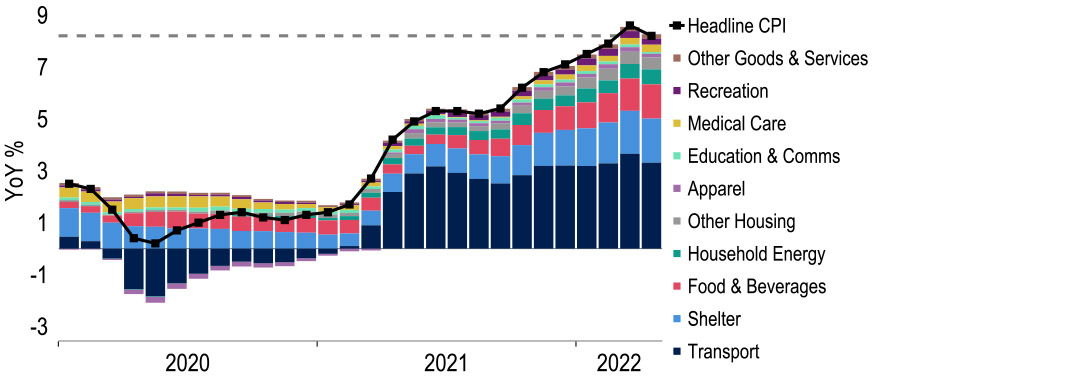

US Consumer Price Index (CPI) inflation slipped back in April. We suspect both the headline and core measures have peaked, but they remain elevated at 8.3% and 6.2%. Hence the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC)’s primary concern remains to curb price pressures to a degree consistent with its policy mandate. Its ‘frontloading’ strategy was confirmed by a 50 basis point hike in the Fed funds target range to 0.75-1.00% earlier in May and by leaving 50 basis point moves on the table at the next two meetings. We then expect a scaling back in the pace of increases, especially as the Fed’s balance sheet contraction (quantitative tightening or QT) starts in early June, thought by members to be equivalent to between one and three 25 basis point hikes. Our base case is that the funds rate tops out at 2.50-2.75% by year-end, followed by a policy hiatus through 2023. But as explained last month, we consider there to be a material chance that the FOMC eases policy at some stage, given risks of an economic downturn. For now activity remains solid, though housing market activity may be weakening rapidly. Although yield curves have fallen back recently, we still judge them to be too steep.

Headwinds to growth continue to build given inflationary pressures on households and the war in Ukraine. Consequently, we have cut our GDP forecasts to 2.8% for 2022 and 2.3% for 2023. Despite these headwinds, inflation is the primary concern and, as such, we expect the European Central Bank (ECB) to also frontload policy via three 25 basis point hikes in the Deposit rate this year, starting in July. In markets, policy normalisation has pushed yields higher and spreads wider, but we see risks of a renewed debt crisis as being overblown. Meanwhile, whilst the euro has been under pressure against the dollar, we see it firming as the ECB hikes rates – we reaffirm our forecasts at $1.10 for Q4 2022 and $1.15 for Q4 2023.

Despite inflation having surged to its highest in four decades, we do not see a consumer-led recession as inevitable: momentum in wages and employment is strong, as are buffers from high savings. Still, real incomes stand to fall; and rising costs squeeze firms’ margins. That is likely to weigh on growth. We have trimmed our 2022 GDP forecast by 0.6 percentage points to 3.4% and our 2023 forecast by 0.5 percentage point to 1.7%. Even so, the extreme tightness of the labour market argues for further swift rate hikes for now. We have brought forward their expected timing, now looking for a Bank rate of 1.75% by year-end. Similarly to the US, we envisage a policy pause, but with a risk that the Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) cuts rates. We still look for the pound to appreciate, especially against the US dollar: we forecast $1.30 at end-2022 and $1.37 at end-2023.

Global

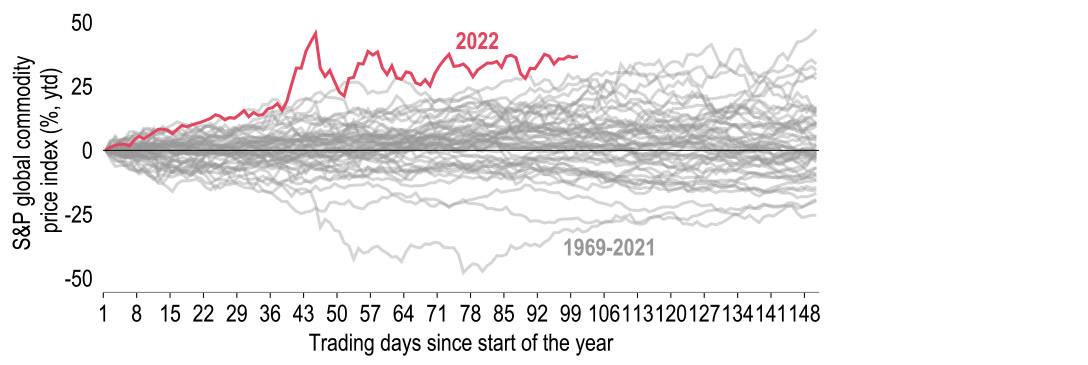

Over six million Ukrainians – roughly 14% of the population – have now fled their country in search of refuge, as fighting continues in the east of the country. Regrettably, the war now looks as if it will be drawn out for longer than expected, potentially for a number of years. Press focus is now more so on the geopolitical issues spurred by the conflict, such as Finland and Sweden’s NATO membership bids, and the European Union’s plans to place an embargo on Russian oil. The latter constitutes part of a wider change in global energy attitudes. Combined with the continued bottlenecks in Russo-Ukrainian influenced commodity markets, the war-induced inflationary pressure is not yet subsiding.

Chart 1: Commodity price pressure shows no sign of letting up as war drags on

Sources: Macrobond, Investec

Also yet to alleviate are the lockdowns in China, which are adding to the inflation backdrop through disruptions to global supply chains. Shanghai is beginning to emerge from restrictions, but will not return to normal until at least mid-to-late June. But activity in Beijing looks to have plummeted. This does not bode well for the Chinese economy in the second quarter, which started badly with a 11.1% year-on-year fall in retail sales in April. Despite policymakers’ vows to support the economy with further stimulus, we have downgraded our forecast for Chinese growth this year to 3.9% from 4.8%, with our forecast for 2023 at 5.4%, compared to 5.0% previously.

Combined with the continued bottlenecks in Russo-Ukrainian influenced commodity markets, the war-induced inflationary pressure is not yet subsiding.

Chinese growth worries naturally spell trouble for the wider economic outlook. In particular, the blockages of global supply chains will undoubtedly weigh on manufacturing output in many economies, and retail trade too if inventories are depleted. But some business surveys, notably the S&P Global PMIs, appear to show industrial output holding up well in most economies. We suspect this may be due to the compilation methodology. The Suppliers’ Delivery Times component is accounted for in a way such that a worsening in supply chains deceptively provides an upward contribution to manufacturing PMIs. However, using the New York Fed Global Supply Chain Pressure indices, the worsening in supply chains has been trending downwards of late.

Notably, the China index has not been updated. But while the production outlook is not exactly rosy, the outlook for household consumption looks to be the crux for global growth. Consumer spending represents approximately 60% of most economies’ GDP, and so with inflation soaring, it is the real income squeeze that will likely induce somewhat of a global slowdown. This is particularly the case for economies that are heavily exposed to energy prices, such as the UK. So, while our assumptions for Russian and Ukrainian growth – at -10% and -30%, respectively – remain unchanged, a multitude of downgrades to individual economies means that our global growth forecast for 2022 is reduced by a sizeable 0.6 percentage point, to 2.7%.

Some of this weakness will spill over to 2023 too, where we now expect global growth of 3.0% rather than 3.4%. Fears of these slowdowns worldwide have gripped markets this month. Equity indices have been sent tumbling – the MSCI World Index is down 17.1% year-to-date. Meanwhile, bond markets have swung both ways: to factor in a greater recession risk; and in expectation of tighter monetary policy despite the growth backdrop. Indeed, it appears as if the general consensus among monetary policymakers is that inflation concerns outweigh those of the deteriorating growth outlook (for now), and that rates must therefore go higher.

Chart 2: Our GDP growth forecasts are downgraded across the board

Sources: Macrobond, Investec

Especially in the US, Fed Chair Jerome Powell noted that everybody is better off with stable prices, even if that requires some pain in the short term. The reinforcement of Fed tightening expectations, in combination with a general flight to safety in light of recession fears, has seen the dollar continue to strengthen. We envisage a point where markets are sufficiently assuaged over the global inflation outlook that they begin to price in easing by global central banks, including the Fed. Combined with a gradual dissipation of risk aversion, despite the more modest growth outlook, this would see an unwinding of recent dollar strength.

United States

The US has been subject to the same inflationary pressures plaguing the world economy, but there are early signs that US CPI inflation has peaked – April’s headline measure eased to 8.3% from 8.5% and the core measure to 6.2% from 6.5%. Although still elevated (and above consensus), we did see signs of comfort. One example is apparel prices, which fell by 0.8% month-on-month, ending a run of six straight gains. Moreover, large swings such as the 18.6% monthly rise in airline fares are unlikely to be repeated. From here, favourable base effects should lend support for an easing in inflation (including the Personal Consumption Expenditures Price Index or PCE measure) over the coming months, including an expected decline in energy and used car prices.

Chart 3: US CPI inflation has probably peaked, but remains elevated

Sources: Macrobond, Investec

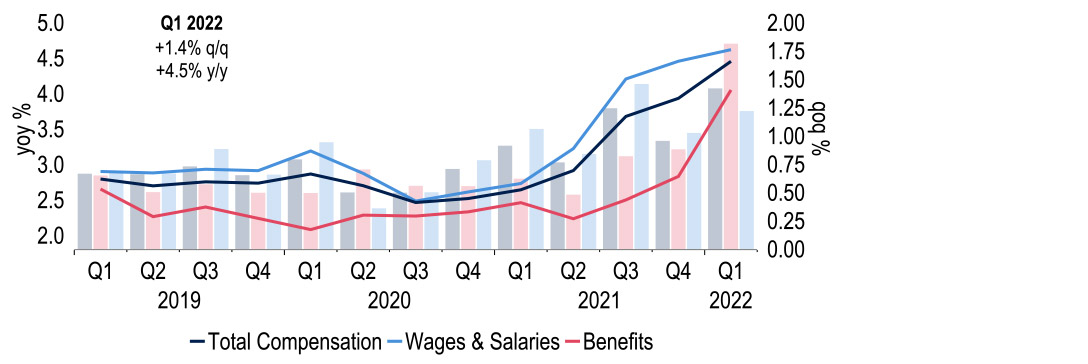

The major medium-term risk to this view is the potential for second-round effects from sustained high wage growth. Here, although the Employment Cost Index surged by 1.4% in Q1, the highest quarterly growth since 1989, the main driver was robust benefits (+1.8%). Wages and salary growth was more moderate at +1.2%, about average for the past year, despite the progressively tighter labour market conditions. This may partly quell second-round fears, but nowhere near enough to prevent the FOMC’s frontloading monetary policy strategy. Concerns though are growing that the scale of Fed tightening could well choke off economic growth.

Chart 4: Employment Cost Index

Columns represent q/q % change, lines represent y/y % change

Sources: Macrobond, Investec

Indeed, Fed Chair Powell himself has admitted that fighting inflation will include ‘some pain’, stoking recession fears. On the face of it, the Q1 GDP report does not help ease such concerns, yet the weak number was induced by a large inventory swing and a deterioration in net trade. Personal consumption actually exhibited robust growth, which seems to have continued into Q2, given strong retail sales in April. That does not, however, detract from risks looking ahead. Higher rates threaten to hit business investment and there are already warning signs from the housing market, including a near 17% slide in new home sales in April. Incorporating the weaker-than-expected Q1, we have downgraded our GDP forecasts to 2.6% (-0.5%pts) for this year and 1.7% (-0.6%pts) next.

Concerns though are growing that the scale of Fed tightening could well choke off economic growth.

After the 4 May 50 basis point hike in the Fed funds target to 0.75-1.00%, Chair Powell stated that 50 basis point increases are also on the table for June and July. We now expect a 50 basis point move in July (previously 25bps), but no longer see a rise in 2023. Slower frontloading to 25 basis point hikes post-summer leaves our forecast cycle peak at 2.50-2.75%. Most FOMC members see this as a ‘restrictive’ level, with the Fed’s plans to shrink its balance sheet from June reinforcing this stance. These amount to a $30bn monthly run-off in Treasuries and $17.5bn in mortgage-backed securities (MBS), with the run-off set to double in September. Fed members suggest this could be the equivalent of one to three 25 basis point hikes. Our recent paper argues that to achieve an optimal balance sheet size, the Fed could keep this policy in place until 2025.

One feature of the Fed’s inflation mandate is that it employs a ‘make up’ strategy, namely that it compensates for past errors in meeting its 2% objective and ‘averages out’ over time. At inception in 2020, this meant that the Fed could run the economy ‘hot’ for a while, as inflation had been below 2% for a period. Does the Fed have the same wiggle room now? In short, no. As an example, over the past five years, core PCE has averaged 2.2% and the headline measure 2.3%, suggesting in principle that the FOMC should run the economy ‘cold’ for a while to get the long-term inflation average back down to 2%. But this is a slight nuance, given high inflation on one side and uncertainties over the pace of growth on the other.

Indeed, Treasuries have been volatile over the past month. 10-year yields have retraced from recent highs of 3.20%, currently trading at 2.73%, as jitters over a hard landing have mounted. Money markets have rallied hard and from this point are pricing a total of 200-225 basis points of tightening, compared with 275 basis points earlier this month. Our own expectation is 175 basis points. Also, as we wrote last month, there is a material chance that the combined effect of higher rates and QT results in a bumpy landing for the economy and encourages the FOMC to adjust rates down during 2023 if it assesses that the curb on price pressures is sufficient. This is not our central view – yet.

Eurozone

April’s Harmonised Index of Consumer Prices (HICP) reading saw inflation remain at its record high of 7.4%. Unsurprisingly, energy prices were a significant upward influence, contributing 3.7 percentage points to the annual rate, but so was food, where prices rose by 7.7%. Have we seen the peak in inflation? We suspect not quite yet; our own forecasts envisage inflation rising to 8% in the near term, before beginning to moderate as energy’s influence starts to wane. Nonetheless, we still see inflation above 6% at the end of this year. Clearly this backdrop is worrying policymakers, both in terms of realised inflation, but also as regards its expected path, with the ECB set of March projections likely to see another notable uplift next month. The labour market outlook and wages in particular will be a key factor in the medium-term outlook and in the ECB’s thinking.

Have we seen the peak in inflation? We suspect not quite yet.

Although conditions remain tight – employment rose 0.5% quarter-on-quarter in Q1, whilst unemployment is at a record low 6.8% – a significant wage response has yet to emerge. These labour market conditions have been set against a thus far resilient economy. But inflationary pressures on consumer spending are mounting, as are downside risks of a near-term loss of Russian gas supplies. Our latest forecasts see GDP growth cut in both 2022 and 2023 by 0.4 percentage points and 0.7 percentage points respectively to 2.8% and 2.3%. An assumption within this is that investment is a notably supportive factor in some countries given the drive to diversify away from Russian energy.

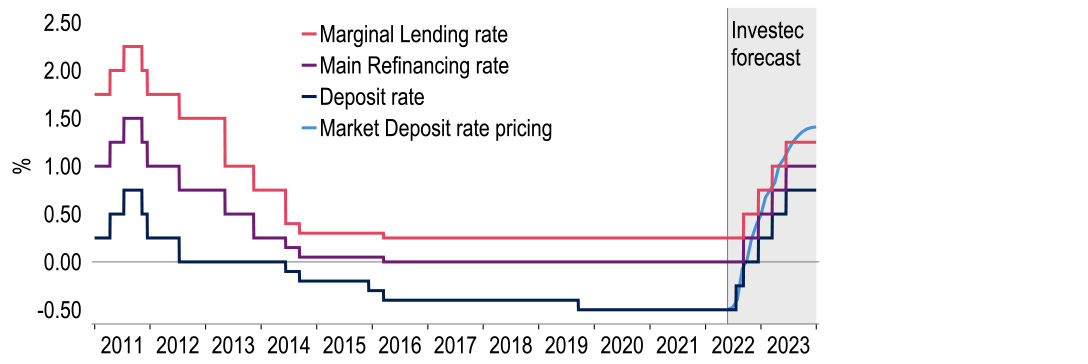

Despite the growth headwinds, inflation remains the primary concern. Here the ECB’s tone clearly appears to be moving in the direction of other central banks and frontloading policy tightening. We now expect rates to begin rising in July with a 25 basis point Deposit rate move. Subsequently, we look for two further 25 basis point hikes in September and December, which would take the Deposit rate to 0.25%, its first foray into positive territory since 2012. This return to a positive Deposit rate should also trigger adjustments in the ECB’s other two policy rates, the Main Refinancing or refi rate and Marginal Lending rate, for the first time since 2016 and ultimately a symmetrical 25 basis point rate corridor either side of the refi rate. In 2023, we expect two 25 basis point hikes as the ECB moves toward neutral rates.

Chart 5: Key ECB policy rates: Deposit rate expected to return to positive territory this year

Sources: Macrobond, Investec

Reports have suggested that the ECB views this to be about 1.25%. The prospect of a positive Deposit rate has raised a question over whether it will herald the return of the refi rate as the main ECB interest rate. In the short term we suspect not, given the excess amount of liquidity in the system, which we estimate currently stands at €4.5trn. In normal times, the ECB would add or drain liquidity via fine tuning operations, but given the ECB’s policy on open market operations* and the amount of quantitative easing (QE) in the system, draining liquidity so that it equals bank reserve requirements looks unfeasible given the size of operations needed.

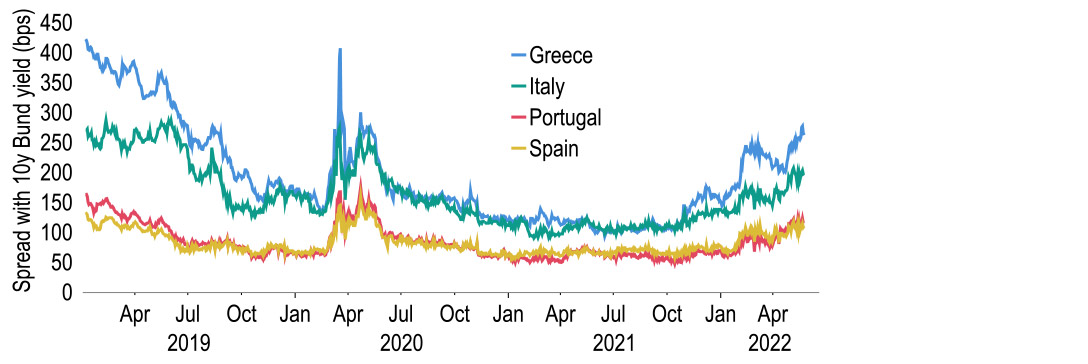

Shrinking its balance sheet would begin to address this, but at present such talk looks premature. Current guidance is that reinvestment of QE principal will continue until at least the end of 2024 for the pandemic emergency purchase programme (PEPP), and an ‘extended period of time’ after the first rate move for the Asset Purchase Programme (APP). For the latter this is vague, but to us a move towards QT during 2023 is possible. Just illustratively, if the ECB were to begin shrinking its balance sheet via natural runoff in 2023, it would be at half the pace of the Fed. A consequence of normalisation has been a rise in sovereign yields, for example 10-year bunds are up 112 basis points to 0.91% this year. However, this rise is more pronounced in Southern Europe, prompting a widening in spreads, particularly in Greece (275 basis points) and Italy (203 basis points), which is once again raising questions over fragmentation risks in EU19 markets.

However, whilst yields have risen, funding costs remain far below previous peaks. For example, in Italy, yields at issuance so far this year have averaged 0.42%, way below the 3.6% in 2011. Therefore, we see the risks of a debt crisis 2.0 as being exaggerated. Nonetheless, the ECB will be mindful of the effects of its policy. Policy and rate differentials are also playing a key part in foreign exchange markets. In the case of the euro, we judge it has been undervalued versus the US dollar since 2014, when rates went negative. Broadly, we continue to view a move out of negative rates and discussions around QT in 2023 as being supportive of the euro and, as such, we maintain our end-2022 and end-2023 €:$ forecasts at $1.10 and $1.15.

Chart 6: Yield spreads widen, but remain below pandemic peaks (bps)

Sources: Macrobond, Investec

United Kingdom

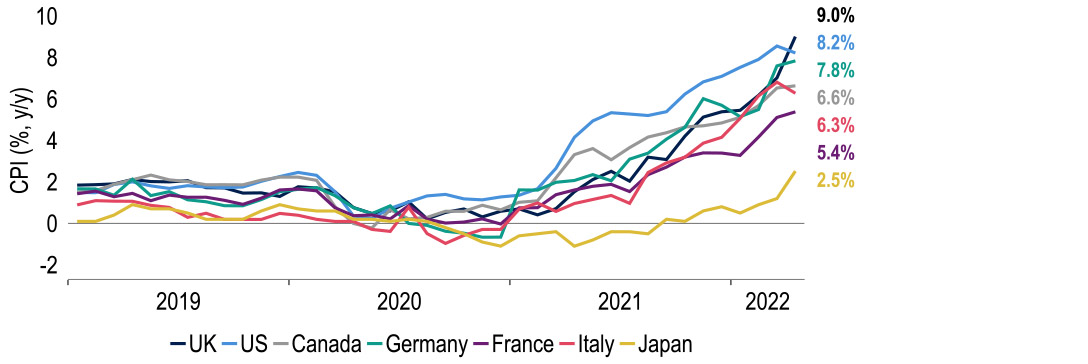

The cost-of-living crisis remains front-page news in the UK: the CPI measure that the Bank of England targets hit 9.0% in April. This is not only its highest in four decades, but also higher than in all of its G7 peers. Nor is this likely to be the peak: we now anticipate it will hit 10.3% in October and retreat only slowly from there, falling below 2% only in Q4 2023. Worries are now centred, understandably, on whether discretionary household spending will be squeezed to the extent it tips the UK into a consumer-led recession. In our view, that is not inevitable. For one, the red-hot labour market can offer support to incomes.

Chart 7: UK consumer price inflation is now the highest in the G7

Sources: National statistics offices, Investec and Macrobond

Competition for workers is very strong, with the number of vacancies now surpassing the number of unemployed for the first time. This stands to support wage growth, thereby also enticing more people back into the labour force: unlike in the US and the Eurozone, the participation rate has barely risen from its pandemic trough. Moreover, households benefit from strong balance sheets, with the saving rate still far above previous troughs and cash holdings – which can most easily be run down – £158bn above pre-pandemic trends (‘excess savings’). But that is not to say the outlook is rosy. We have cut our GDP growth forecast for 2022 by 0.6 percentage point to 3.4% and our 2023 forecast by 0.5 percentage point to 1.7%.

Worries are now centred, understandably, on whether discretionary household spending will be squeezed to the extent it tips the UK into a consumer-led recession.

This is because some weakening in growth, including in consumption, looks hard to avoid, with the spending power of those on the lowest incomes and with little or no assets squeezed the most. Even in aggregate, the share of household disposable incomes spent on energy alone stands to rise sharply. Moreover, margin squeezes for firms are likely to trigger some easing in labour demand and rising unemployment in late 2022 to early 2023 (to a peak rate of 4.7%, we estimate, from 3.7% now) and hold back investment. Ultimately, weaker growth can be traced back to the negative terms of trade shock from further Covid-19 disruptions to global supply chains and a more protracted war in Ukraine than previously thought.

Because the cost squeeze for firms is not solely due to the vagaries of world prices, and specifically because the extreme tightness of the labour market portends further wage rises, we view this as leaving little choice but to press on with additional frontloaded policy tightening for the Bank of England, to cool demand. Indeed, we now see 25 basis point rate hikes in July, August and November, giving a year-end Bank rate of 1.75%. MPC members have oscillated in recent meetings, in the sense that the dissenters have swung between advocating more hawkish and more dovish decisions than those ultimately taken. The MPC looks likely to receive the backing it needs to keep on hiking policy relatively aggressively in the near term from greater fiscal largesse.

Further fiscal support to households hit the most by the surging cost of living has now been announced, following hot on the heels of Sue Gray’s ‘Partygate’ report. The scale of spending has been upped significantly from March to £36bn, of which only £5bn is to be funded through windfall taxes on oil and gas companies. The rest would appear to come from higher borrowing and using some of the ‘war chest’ built up partly from past borrowing having been successively revised down. Come 2023, however, we anticipate that weakening momentum in inflation will allow the MPC to halt tightening as growth and the labour market respond to higher rates.

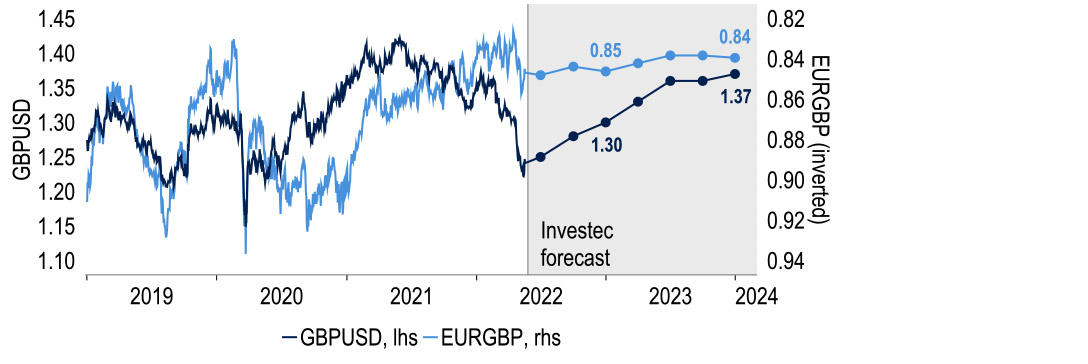

Indeed, although not our baseline, we see a chance this response is larger than intended, and that the MPC eases rates rather than hikes further next year. Even so, from the currency perspective, we see the most likely scenario to be a recovery in sterling following its weakening from the start of the year. The largest move is likely to be against the US dollar, whose relative rate differential and safe haven appeal we expect to diminish over time. We expect cable or pound-dollar levels of $1.30 at end-2022 and $1.37 at end-2023. Against the euro, we foresee more limited gains. Some of the gloom in macro expectations for the UK may be overdone, but as policy rates start to rise in the euro area, this may support demand for euro. We forecast euro-pound at 85p at end-2022 and 84p at end-2023.

Chart 8: Sterling looks poised to strengthen most against a retreating US dollar

Sources: Investec and Macrobond

Get more FX market insights

Stay up to date with our FX insights hub, where our dedicated experts help provide the knowledge to navigate the currency markets.

Browse articles in

Please note: the content on this page is provided for information purposes only and should not be construed as an offer, or a solicitation of an offer, to buy or sell financial instruments. This content does not constitute a personal recommendation and is not investment advice.