An unusual December vote

Prime Minister Johnson’s election call followed an unsuccessful attempt to push Brexit through Parliament at speed last month, to meet the (then) 31 October deadline. Johnson aims to secure a comfortable working majority. This would enable him not just to pass the necessary legislation for the UK to leave the EU by 31 January next year, but also to gain a sufficient parliamentary mandate to follow his agenda over a full five-year term.

It may have been possible for the PM to have passed both a Meaningful Vote on Brexit and the Withdrawal Agreement Bill (the necessary legislation) through parliament without an election, albeit over several weeks to enable full parliamentary scrutiny.

Accordingly, Johnson has been subject to criticism by stating the election was necessary to “get Brexit done”. That said, the arithmetic in the House of Commons was rendering it close to impossible to pass legislation generally. Due to expulsions, defections and a by-election, the Conservatives were in the minority by 24 votes shortly before Parliament was dissolved.

The shortfall had been as high as 45 before several Tory MPs regained the party whip and before the election of a new Speaker. Note too that the arithmetic includes support from the 10 DUP MPs who were in a (somewhat battered) confidence and supply arrangement with the Conservatives.

At the time of writing, we did not have a full picture of Johnson’s non-Brexit policy agenda. But at the start of the week, he announced that the reduction in corporation tax from 19% to 17% would not go ahead as planned next year. This is consistent with the government’s priority lying with raising public spending in areas such as health and education, and also that its own proposed fiscal rules are biting constraints. Johnson’s Conservative Party is set to publish its election manifesto over the next few days. Meanwhile, the Labour Party has confirmed that it will reveal its full policy plans on 21 November.

Of course, the coming election comes just 2½ years after Theresa May’s attempt to increase her small majority in June 2017. The result was not what May had planned. The Conservatives ended up as the largest party, but short of an effective majority, leading to a deal with the DUP. Recent history does not bode well for a conclusive result. Two of the past three elections have resulted in hung parliaments (after the 2010 election, the Tories and the Liberal Democrats entered a coalition together). In fact, the Conservatives have not gained an overall majority in the Commons of 50 or more since Margaret Thatcher won the 1987 election.

As the section on the opinion polls below explains, the Tories have enjoyed a bounce since June. Initially, this coincided with Johnson becoming Conservative leader and prime minister. More recently, the Brexit Party’s decision to withdraw from 360 seats has benefited the Tories. Indeed poll averages show an average lead of 11% over Labour, with recent polls showing a margin of up to 18% (Kantar on 19 November).

Conservatives appear concerned at such voting patterns resulting in lost seats in various regions. These are London, the south-east and the south-west.

Prime Minister, Boris Johnson, at the recent CBI conference announcing corporate tax will be maintained at 19% rather than cut to 17%.

How should we interpret the polls?

Historically pollsters have used a Uniform National Swing (UNS) to convert polling percentages into seats. This works by assuming a fixed change in the share of the vote for each party in each constituency since the previous election. Using UNS recent polls point to a Conservative majority of around 60. But the use of UNS looks too simplistic, especially at this election, as a material decoupling of voters’ traditional party allegiances is set to take place. Top of the list here is the alignment with the parties’ stances on Brexit. A higher degree of tactical voting may well occur as well, for example in 60 seats where the anti-Brexit Liberal Democrats, Greens and Plaid Cymru have agreed not to stand against each other.

Indeed the Conservatives appear concerned at such voting patterns resulting in lost seats in various regions. These are London, the south-east and the south-west. Meanwhile, most of the party’s 13 seats in Scotland are vulnerable. The question is the extent to which net losses there are offset by gains elsewhere in the UK, especially in the Midlands, the north-west and Wales. Based on regional polling, our hunch is that they can. But there are still big question marks.

One possible answer is a new polling technique known as MRP (Multilevel Regression and Post-stratification). In short, this models voting patterns according to defined voter characteristics nationally with a variable relating to individual constituencies which can adjust (for example) for factors such as the 2016 EU referendum vote. While we are wary of looking for a polling ‘holy grail’ we suspect that MRP polls (once they are published) will be a useful tool to supplement the more established techniques.

The prospective outturn of this election looks even less clear than two years ago. On current poll ratings, it seems reasonable to suggest that the Conservatives will get an overall majority. This is despite the complications of the various quirks. But as we remind readers below, a stronger lead in the polls at the same stage of the campaign in 2017 almost evaporated by polling day. A hung parliament is also a real possibility.

Since Boris Johnson became prime minister, the polls have shifted from the Conservatives being a fairly modest 4 points ahead of Labour to the double-digit lead currently seen.

The key point here would be the whether the Conservatives could form a government or whether there could be a workable deal between Labour, the Liberal Democrats and the SNP. Markets here would weigh up the prospect of the implementation of Labour’s programme with the chance of a second Brexit referendum and a Scottish independence referendum. Almost needless to say, this outturn would involve a considerable level of uncertainty.

By contrast, a Tory majority (at least a comfortable win) would probably result in the passage of the Brexit legislation through Westminster by 31 January. Sterling would be likely to rise comfortably above the $1.30 level for a while. That said, we suspect that markets would promptly turn their attention to the detail of a UK-EU free trade agreement. Specifically, the question would be whether such a deal could be struck. If so markets would ask how ‘frictionless’ trade would be and if not, whether the PM would be willing to extend the transition period beyond 2020. But those thoughts will be for after 12 December.

What election outcome can we expect?

Since Boris Johnson became prime minister, the polls have shifted from the Conservatives being a relatively modest 4 points ahead of Labour to the double-digit lead currently seen. Based on a UNS, which assumes that changes in the national vote are observed across all constituencies, such a lead would suggest that the Conservatives are set to gain a majority of around 60 in the election.

However, the accuracy of such rudimentary models is questionable in the current fractured political environment which has seen traditional party allegiances cast aside. According to NatCen, voters now more closely associate themselves with how they voted in the 2016 EU referendum than with political parties. So as the main established parties have generally strived to be a broad church of so-called Leavers and Remainers, this has opened up a vacuum for the fringes of the political spectrum to pick up voters.

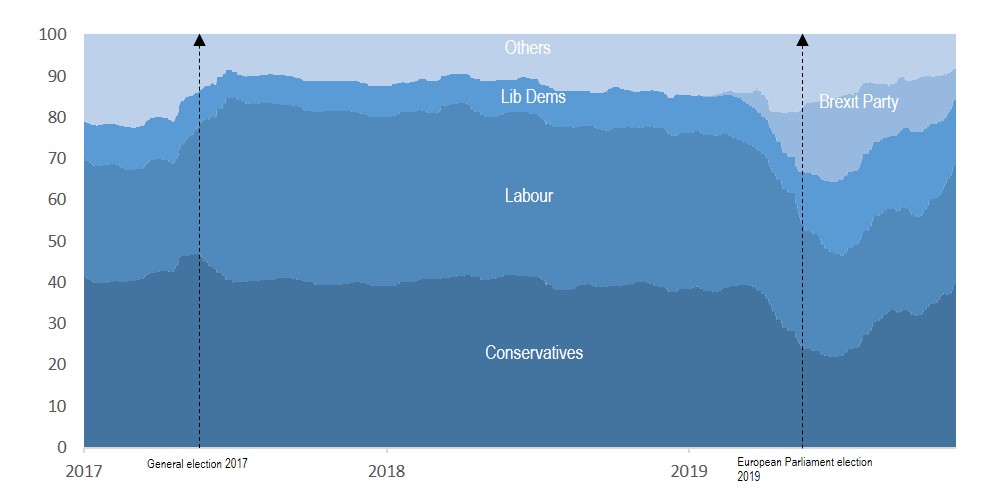

Most successful in doing so has been the Brexit Party, which after just four months of existence managed to become both the largest British and European party in May’s European Parliament elections. While its support has since waned, its residual popularity means that it could well split the eurosceptic vote (Chart 1), prompting party leader Nigel Farage to seek a “Leave alliance” with the prime minister.

Finding his overtures rejected, he ultimately took the unilateral decision not to contest the 317 seats won by the Conservatives in 2017 (and 43 seats currently held by other parties). Instead, the party will concentrate its resources on trying to win Labour-held constituencies in Northern England, which Johnson hopes to capture in his bid to win a parliamentary majority. Meanwhile, the Prime Minister also risks being squeezed by the “remain” contingent of the electorate, with the SNP and the Liberal Democrats expected to make gains in Scotland and Southern England respectively.

Share of Westminster polling intentions (%)

Source: Britain Elects

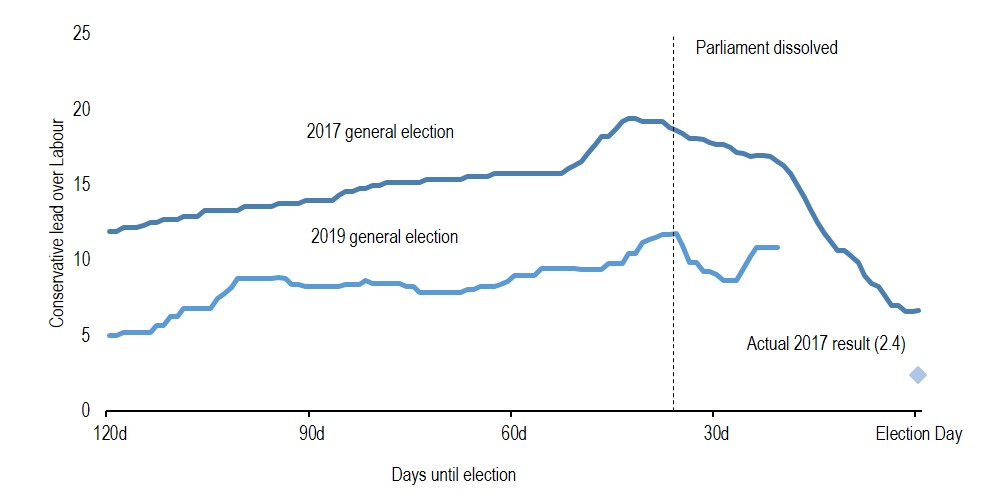

To illustrate how much fortunes can shift with three weeks of campaigning still to go, we note that the Conservatives’ current lead over Labour is lower than it was at the same stage of the 2017 general election (Chart 2).

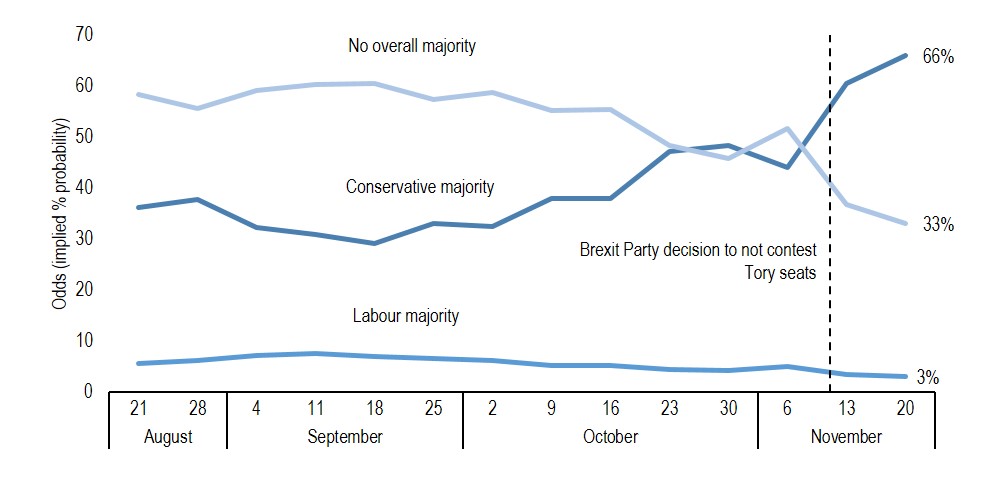

Consequently, while Betfair odds indicate the likelihood of an overall Conservative majority is 66%, a hung parliament is priced as being the next most probable scenario at a sizable 32%. Still, this is an improvement since MPs first sanctioned a 12 December general election in late-November when the odds were closer to 50/50 (Chart 3).

So while it looks as though the Conservatives will win a reasonable majority, this is by no means assured given the various dynamics at play.

Johnson has a smaller lead at this stage of the campaign than May did

Source: Poll of polls, Britain Elects

Betfair odds suggest a two-thirds probability for a Tory majority

Source: BetData

Will a majority for the Conservatives “get Brexit done”?

If the outcome of the 12 December vote is a Conservative majority, even a small one, we would expect Boris Johnson to successfully see his deal (and legislation) pass through Parliament and become law.

That should happen in time for the UK to leave the EU by 31 January 2020, with all Tory candidates standing in the general election supporting Johnson’s Brexit deal. We do not expect EU ratification to be a significant hurdle and by 1 February 2020, we would assume the UK to have exited the EU and entered the transition period.

This transition is scheduled to run until the end of 2020, though with a one to two-year extension possible. Even if the Brexit legislation passes into law smoothly, one uncertainty persisting is the direction a Tory government would take talks on future trading arrangements. In the not too distant future, no later than 1 July 2020, a decision needs to be made on whether to exit the transition period at the end of 2020.

The Brexit Election: The election is being widely termed the ‘Brexit Election’ with the outcome of the vote seen as critical in determining if, when and how the UK exits the EU and the shape of the future trading relationship.

Related to this, given the political declaration is non-specific and non-binding, there also remains a question of the precise nature of the Free Trade Agreement. There even remains the possibility that the Johnson administration fails to agree a future trade deal and therefore leaves the transition phase onto WTO terms. This though is not our central expectation.

If the Conservative Party does not secure a majority, then a range of other options are at play. If it falls just a few seats short, it might look to secure a confidence and supply agreement with a smaller party. That might be more difficult than in 2017 when the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) entered into such an arrangement.

This time, smaller (and larger) parties would struggle to back PM Johnson’s Brexit plan presenting a possible showstopper to such an arrangement. If the Conservative party were unsuccessful in this, then it is likely other party groupings would seek to capitalise and see if they could gain sufficient numbers to win the confidence of the House of Commons and therefore to govern.

What happens if the Conservatives fall short?

Current polling implies that the Labour Party is likely to secure the second largest number of seats. However, it is unlikely to be in a position to govern successfully on its own. It is unclear whether Labour would be able to reach a coalition deal, inter-party agreement or confidence and supply arrangement with enough other party MPs.

Indeed, Liberal Democrat leader Jo Swinson has refuted the idea of joining a Jeremy Corbyn-led government. Meanwhile, Scottish National Party (SNP) leader Nicola Sturgeon is looking for commitments on a second independence referendum. If these barriers are overcome and such a government is formed, the UK’s Brexit path could look quite different to that under a majority Conservative administration.

Firstly, Corbyn has indicated he would seek another extension to the Brexit date beyond 31 January 2020. That would likely be requested from the EU on the basis that the UK government wished to hold a vote on various Brexit possibilities, such as a referendum. Of course, if no government is formed, it would be back to elections again.

Labour has previously pressed for a confirmatory vote on any Brexit deal. It now plans to renegotiate Johnson’s deal over several months, seek a closer trading relationship and put this to the public vote.

However, we could be in for some cross-party wrangling on the precise shape of any referendum on that deal, and other options, that followed. The Liberal Democrats, if part of any government arrangement, would likely press for a straight revoke ‘Article 50’ vote in Parliament, whilst the SNP also has a strong desire to remain and would no doubt wish for this to be a clear and discrete decision in any referendum.

One issue is that structuring the referendum to deal with these possibilities could be complicated. For example, one question is if Corbyn would be content to have a first or structured vote on leave versus remain, before asking the question of whether to back any new deal he has secured.

Any second referendum is unlikely to resolve the issue of divisions amidst the public (and MPs) over Brexit and would not likely mark the end of the road in political wrangling over the shape of Brexit. Finding an operational system for post-Brexit relations would still likely be an ongoing issue.

How about sterling?

The likelihood that the Conservative Party secures a majority also looks to be the baseline assumption amidst most investors. Sterling has climbed as the polls have widened the Tory lead over Labour though more recently this has slipped back. A Tory majority is seen raising the chance that Brexit uncertainties fall away more quickly with, as Boris Johnson has an “oven-ready” deal set.

As such, sterling likely rallies further on news of a Conservative majority with this not yet fully priced in, though the upside may be capped by questions over future trading arrangements remaining open. Under a hung Parliament (or a Labour majority), sterling appears set to reverse the gains made over the past month.

While the possibility of a ‘softer’ Brexit might soften the blow for sterling, further near-term uncertainty alongside questions over the higher taxation burden that would likely exist for business under a Labour-led administration will likely continue to drag the pound lower. The key points on business policies already laid out by the parties, ahead of the publication of manifestos, are summarised below.

- Corporation tax will no longer be cut from 19% to 17%. The £6bn (or so) that the party estimates would be saved is said to be channelled into public services.

- The party has promised to cut business rates further, particularly for SMEs; there will be a big business rates review. Also, Boris Johnson has pledged to reduce National Insurance Contributions.

- There are plans to introduce a points-based immigration system and remove the preferential treatment of EU migrants over welfare and charging for access to healthcare. The party is aiming for an “equal system” rather than a target.

- PM Johnson has promised more infrastructure spending such as the West Midlands Metro extension and Northern Powerhouse Rail. Modernising roads, better bus services and better cycleways across the whole country are also on the list.

- It plans for larger companies to hand 10% of their shares to workers over 10 years. The “shares for workers” scheme would oblige companies with more than 250 employees to give equity to so-called inclusive ownership funds at the rate of 1% each year over a decade.

- A “revolution in the labour market” by introducing sectoral collective bargaining is envisaged, promising a (voluntary) 32-hour working week by 2030 and banning zero-hours contracts.

- A windfall tax on oil companies as part of its attempts to shift the UK towards a low-carbon economy is planned.

- A plan for a swath of nationalisations including water companies, railways, Royal Mail, National Grid, private finance initiative schemes and BT’s network arm.

- A ramping up of spending on public services and £400bn of additional state borrowing - much of it for investment in infrastructure.

- The Liberal Democrats plan to scrap business rates and replace them with a commercial landowners’ levy. Beyond this, their focus so far is on stopping Brexit which they say “has distracted the government from addressing the very real issues in our economy”.

Browse articles in

Please note: This page is provided for information purposes only and should not be construed as an offer, or a solicitation of an offer, to buy or sell financial instruments. This page does not constitute a personal recommendation and is not investment advice. Any predictions, or forecasts expressed are based on significant judgement and analysis of available information at the time of writing and actual outcomes may be materially different and may be affected by political, economic or any other relevant circumstance changes.