South Africa is at base camp of the Covid-19 peak. Over the weeks that follow our resilience as a nation will be put to the test yet again and how we come out on the other side will depend on whether we can use our shared philosophy of Ubuntu - “I am because you are” - to voluntarily regulate our behaviour for the greater good.

“In the post peak era, we need a policy framework where people understand the fundamental link that their actions will impact on not just their own livelihood, but the prosperity of our nation. Our future depends on it.”

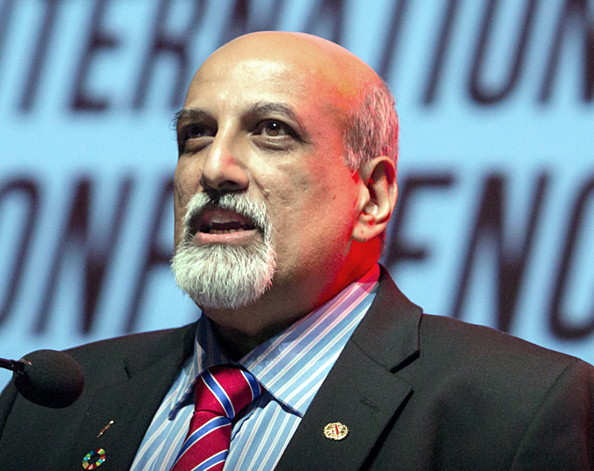

These were the words of Professor Salim Abdool Karim, Chairperson of the Covid-19 ministerial advisory committee, and Director of the Centre for the AIDS Program of Research in South Africa (CAPRISA).

In an interview with Gugulethu Mfuphi for the ninth episode of Investec Wealth & Investment’s webcast series, “Markets and investing in a time of Covid”, Karim says that South Africa is now in the awkward situation of easing the lockdown when the number of cases is rising – a move which flies against World Health Organisation (WHO) guidelines that only advise lifting restrictions once containment of the virus has been achieved. But like India, Pakistan and Russia, South Africa can’t afford the enormous cost to the economy.

Prefer to listen on the go?

Catch the full discussion with Prof Karim and Gugulethu Mfuphi in this podcast.

Subscribe to Investec Focus Radio SA

South Africans don't really yet have a full appreciation of the rapid way in which this disease can cause havoc.

Cases are now naturally rising rapidly as people’s movement increases, but Karim believes that reverting back to a hard lockdown should only be a measure of last resort. Behavioural change, he says, is the most sustainable solution.

“We saw from our experiences in HIV and more recently from the experiences in New York that as the number of cases rises quite rapidly, you reach a point where many people know a family member, a friend, a work colleague, a neighbour or a famous person who became infected and possibly who died. When that happens, this disease becomes personal. When it becomes personal you then have a personal motivation to change your behaviour.”

To ensure that this happens, Karim doesn’t believe in heavy-handed tactics. “I think we're going to have to find a way to ensure that we create adequate incentives for people to adopt the prevention measures because an enforcement and punishment mechanism doesn't really work well in public health. You can't go around fining people or putting them in jail because they don't wear masks or because they're not social distancing. It's not practical.”

The Covid-19 paradox

In March, the experts, including Karim, expected the worst – a dramatic pandemic that would infect millions of people and obliterate the country’s already fragile healthcare system. Thanks to the fast, decisive response of President Ramaphosa, this didn’t happen, says Karim, and South Africa kept ahead of the disease initially.

“On the 26th of March, the day on which we had the lockdown, the number of cases in South Africa drastically dropped. We moved from cases doubling every two days to cases doubling every 15 days – the virus transmission had slowed.”

Ironically the success of the lockdown in flattening the curve has made a lot of people complacent. “That’s the paradox, the reason you are safe at this point and you don't see the cases is because you are at home,” he says. “South Africans don't really yet have a full appreciation of the rapid way in which this disease can cause havoc,” he says. “In New York patients were dying in the corridors because there just weren't enough beds.”

“That’s the paradox: the reason you are safe at this point and you don't see the cases is because you are at home."

Another area where we have been spared the worst-case scenario so far is our mortality rate. While the case fatality rate in South Africa and the rest of the world is highest in those who are older than 70, there is one marked difference here: fewer people are dying. “Part of the reason for that is because of our youthful population – we have a higher proportion of our population that is below 60,” explains Karim.

While the initial panic in South Africa was around what would happen to people with HIV and TB, these have turned out to be relatively minor risk factors thanks to our young nation. The real killer is diabetes which, according to a study, is attributable for 56% of all Covid-19 deaths in the Western Cape, says Karim.

A new vision of 2020

A snapshot of the year that was and why it has helped us rediscover our humanity.

“There's no guarantee we are even going to be able to make a vaccine.”

“I'm optimistic that we'll have a vaccine, but I've been working for over 30 years on an HIV vaccine unsuccessfully, so we have to accept that science takes time. Until we have a cure or a vaccine, we're going to have to learn to live with this threat.”

When the Covid-19 dust settles and even if a vaccine is found, Karim says things will not go back to normal. “We can't expect that we will live our lives as we were on the 4th of March before our first case. That's gone.”

The behavioural changes that we’ve adopted during this pandemic must stay in place to help prepare us for future viral threats, he says. “If this Coronavirus could come into humans from bats through pangolins, in all likelihood we should expect that we are at risk of other viruses, other kinds of diseases.”

Fortunately, the South African medical fraternity is at the forefront of Covid-19 research, says Karim, who points out that there are “huge” biological research programmes in place locally, including studies into antibodies in convalescent patients and genetic mutations of the virus. In addition, the Oxford University vaccine trial has been extended to South Africa and we are also participating in the WHO’s Solidarity trial.

It is thanks to the history of our healthcare system that we are able to contribute at such a high level globally, he says, pointing to the existing framework that was built for HIV and TB research. “We are now piggybacking on all of that infrastructure built over decades to be able to respond to Covid-19.”

Trust us to manage your wealth today

The “difficult truth”

When he addressed South Africa on Easter Monday, Karim predicted that the curve would be flattened, but that once lockdown eased up, cases would quickly increase. “I called it at the time ‘the difficult truth’ and now we are living that difficult truth that the cases are going to rise.”

So, what’s in store for us over the next few months? “We can expect to see the peak of infections sometime around August, late July,” says Karim who warns that the number of cases will become exponential.

“The epidemic is doubling now in about 12 days, so if today we have, say, 150,000 cases, in 12 days’ time we're going to have 300,000 cases, in another 12 days’ time we're going to have 600,000 cases, in another 12 days’ time, 36 days from now, we're going to have 1.2 million cases. So, you see how in a matter of 36 days you go from 150,000 to 1.2 million.”

However, if the public sticks to the routine of social distancing, wearing masks and hand hygiene, Karim is hopeful that we can slow down the doubling time as we did during lockdown, keeping the peak within the capabilities of the health care system.

"So, you see how in a matter of 36 days you go from 150,000 to 1.2 million.”

“Once that happens, we'll get a little plateau that will occur, it will flatten off as we are able to start dampening down the outbreaks that will occur.”

As cases drop, a 14-day period of continuous decline is necessary before we can declare a stage of containment, explains Prof Karim. “Containment means that we'll still see cases, but they will be sporadic, and they will be little outbreaks.” Even at this stage, as China, South Korea and Singapore can attest to, larger flare ups are possible.

To avoid this, the country will have to go into a phase of vigilance, religiously sticking to the rules. “Even though we will be fatigued, even though we will be fed up, we are going to have to just think to ourselves: ‘is my being fed up reason enough that I'm willing to put myself at risk?’”.

We will not go back to living our pre-Covid lives

In a post-Covid world where hugs, handshakes and blowing out candles will be fondly remembered as things of the past, South Africans must continue to apply the lessons learnt during the pandemic, says Karim. “We have to find a new way in which we are going to live but live we shall. Live in a way that we have control over that risk.”

Fortunately, South Africa has a distinct advantage, he believes: “We come from a philosophy that we don't just care about ourselves, our individual risk; we care about our communities and we have a rich history of doing that. And so, if we can build on that, that is a fundamental basis on which we can mitigate our risk in the long term.”

About the author

Ingrid Booth

Lead digital content producer

Ingrid Booth is a consumer magazine journalist who made the successful transition to corporate PR and back into digital publishing. As part of Investec's Brand Centre digital content team, her role entails coordinating and producing multi-media content from across the Group for Investec's publishing platform, Focus.

Please refer to the W&I Webinar Disclaimer and Data Protection Notice for the terms and conditions governing W&I webinars.

Get Focus insights straight to your inbox